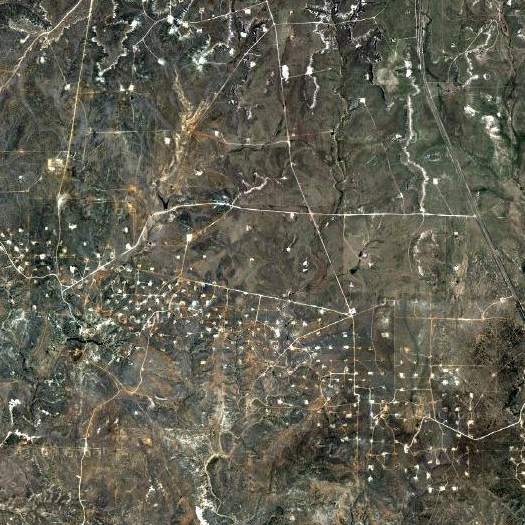

[A portion of the Cliffside field snakes tentacles across flat pasture concealing ancient anticlines.]

Just outside Amarillo, Texas, the Cliffside field stores much of the nation’s helium reserves in a naturally-occurring geologic dome. It is part of a complex of partially-privatized fields, mines, domes, and pipelines which extends nearly two hundred miles north-south, from the Texas Panhandle to Oklahoma. A recent article in Seed Magazine describes the complex, whose helium stockpile is by far the world’s largest, and its role in the increasing global scarcity of helium, which is a critical element in a number of industrial and scientific processes, yet relatively easily escapes the earth’s atmosphere for outer space.

This industrial landscape is only possible due to the particular geologic conditions of the region: beds composed primarily of “Brown dolomite” are sufficiently receptive to helium (having been discovered because they contained natural — though less concentrated — helium reserves), while the “Panhandle lime formation”, which is layered immediately on top of those beds, provides a natural “caprock”, penetrated only by the airtight injection wells (PDF). With those wells, production plants, maintenance roads, and pipelines running across the surface of these formations to prosthetically adapt bedrock to use in industrial process, the ground itself has assumed a hybridized and mechanical nature, comprising a very literal landscape machine.

I’ve noted before Pierre Belanger’s predictions about the bio-physical landscape as infrastructure, which he describes as having been “historically suppressed”, but ripe for resurgence as “a collective system of essential services, resources, and agents that generates and supports urban economies”. While the helium industry may not have a very long future, perhaps the geo-physical landscape has also been overlooked, and may also be useful to the development of such a system.