Things have been terribly quiet here at mammoth this fall. (Assuming that by “here” we mean “here, on the blog”; they’ve been quite busy if by “here” we mean “here in Ohio and Virginia”, which is where I’ve physically been. Hopefully I’ll get a chance to recap those adventures soon — there’s been quite a bit to write about.) One of the biggest reasons for that quietness is the enormous amount of planning and energy that’s gone into putting together DredgeFest Louisiana, which we’re very excited to now be able to publicly announce.

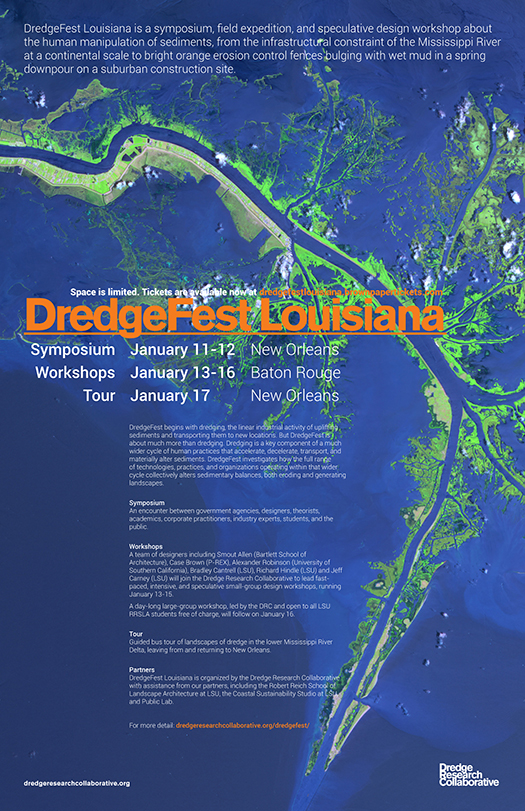

DredgeFest Louisiana is a symposium, field expedition, and speculative design workshop about the human manipulation of sediments, from the infrastructural constraint of the Mississippi River at a continental scale to bright orange erosion control fences bulging with wet mud in a spring downpour on a suburban construction site. It is an encounter between government agencies, designers, theorists, academics, corporate practitioners, industry experts, students, and the public. It’ll be a lot like DredgeFest NYC, but with the emphasis on a lot: bigger, longer, more speculative, more intense. Much like the Mississippi River itself.

It will run January 11-17, 2014: a full week, though the individual components are two days (symposium), one day (tour), and four days (workshops).

It will move between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. The symposium, which opens the event, is in New Orleans. The workshops will be hosted by the Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture in Baton Rouge. The tour, which closes out DredgeFest Louisiana on January 17, will depart from and return to New Orleans.

Perhaps most importantly: tickets for DredgeFest Louisiana are available through Brown Paper Tickets, at dredgefestlouisiana.brownpapertickets.com. For the rest of November, tickets are available at an early-bird discount of 25% off. (You’ll see, if you click over to Brown Paper Tickets, that ticket prices are rather low, at least relative to similar events. This is because DredgeFest is a non-profit event — a labor of love — and we want to make DredgeFest open to as many people as possible. That said, space is limited, particularly for the workshops, so better to reserve tickets sooner rather than later.)

Read on for much more detail about the event theme and components.

Terrain

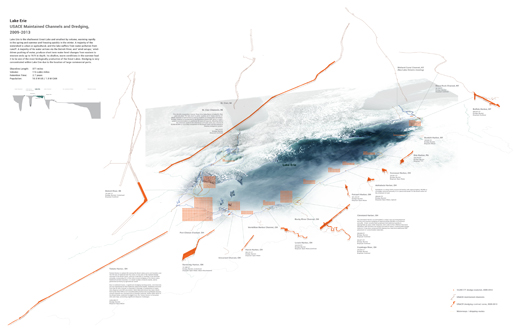

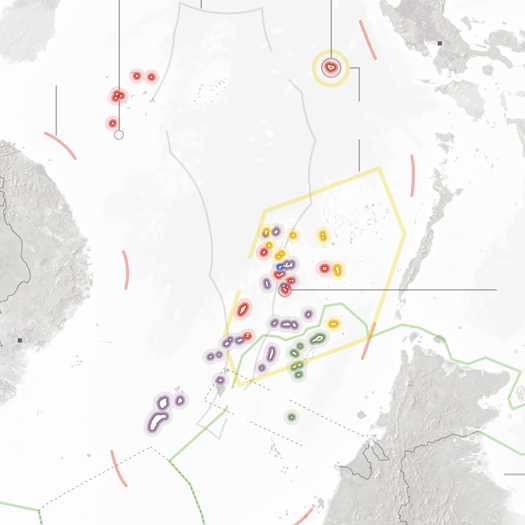

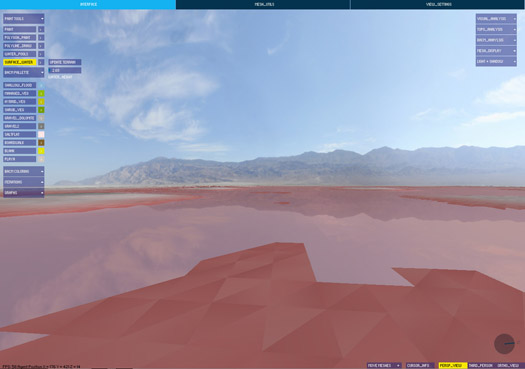

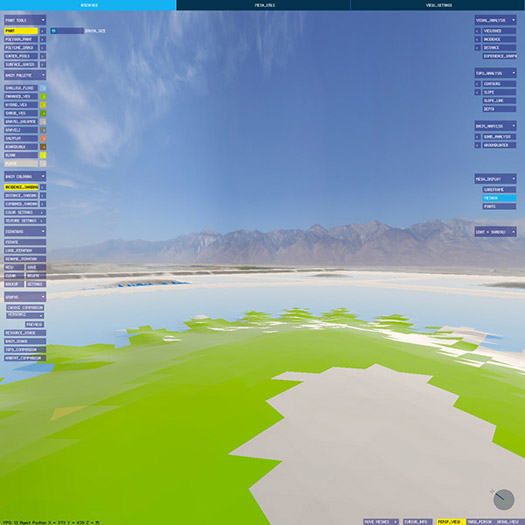

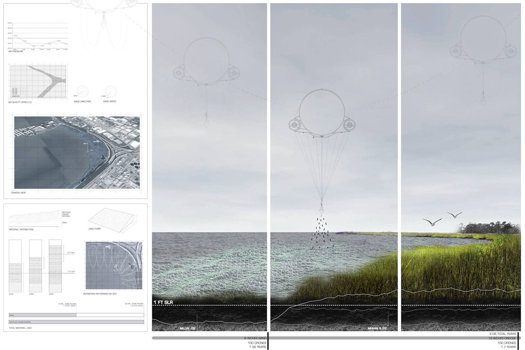

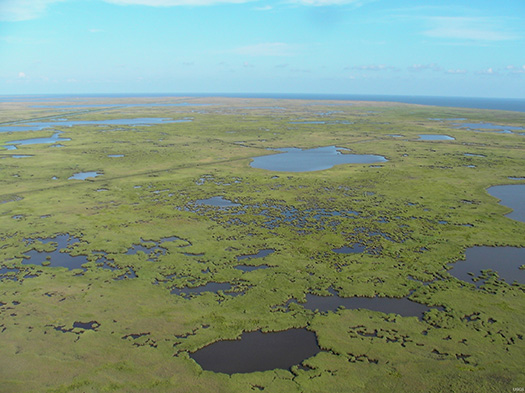

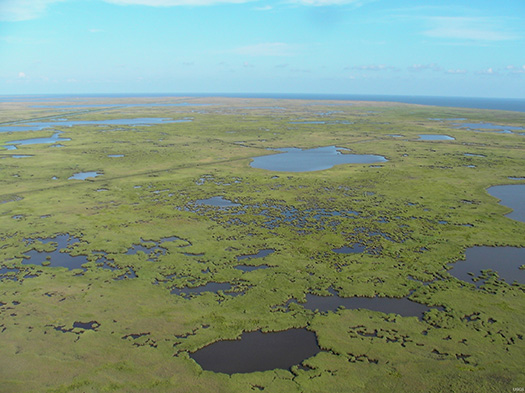

Geographer Richard Campanella has evocatively described the Mississippi River—which is North America’s largest river, discharging more than three times as much water as the next largest river in the United States—as the “land-making machine”. And, indeed, historically, this is what the Mississippi River did: it made land, building its enormous delta—the southern half of the state of Louisiana—over the course of a mere five thousand years, carrying approximately 400 million tons of sediment out of the center of the continent every year, and spraying that sediment around the edges of its mouth. Even today, constrained by levees reinforced with articulated concrete mattresses, locked into a single course at Old River Control, and starved of sediment by upstream dams, the Mississippi River retains potent land-making power, readily evidenced, for instance, by the growth of the Wax Lake Delta, a new delta southwest of New Orleans formed as a by-product of the reorganization of river flows for navigation and flood control. Nearly 200 million tons of sediment still flow every year down the Mississippi and its primary branch, the Atchafalaya.

At the same time, south Louisiana is shrinking. Sea-level rise, salt water intrusion, canal excavation for industrial purposes, and flood control along the edge of the Mississippi River have altered the balance between deposition, subsidence, and erosion. As a consequence, Louisiana has lost over 1700 square miles of land (an area greater than the state of Rhode Island) since 1930, and, without a change in course, is anticipated to double that loss in the next fifty years. Settlements from Lake Charles to Bayou LaFourche to New Orleans are endangered by this loss, both directly—as the land itself disappears—and indirectly, as the loss of barrier islands and coastal marshes exposes settlements to storm surge, while heralding the loss of the terrain that extractive industries, from oysters to oil, depend upon for harvesting resources.

This is the terrain that DredgeFest Louisiana enters into.

Topics

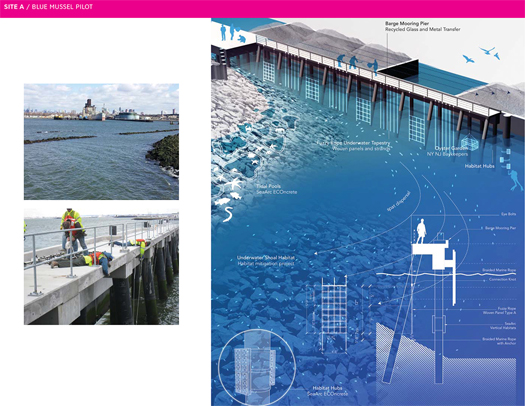

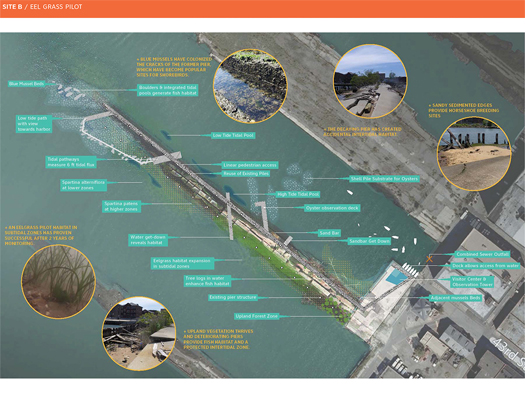

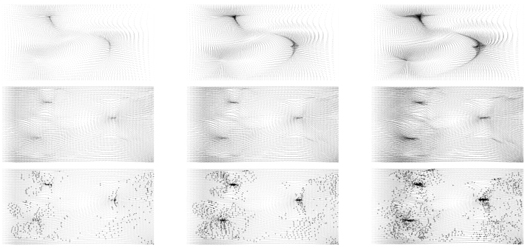

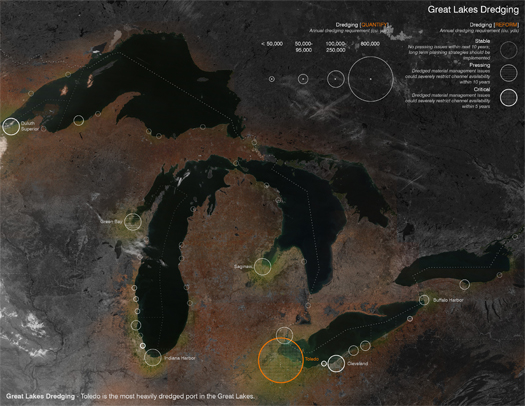

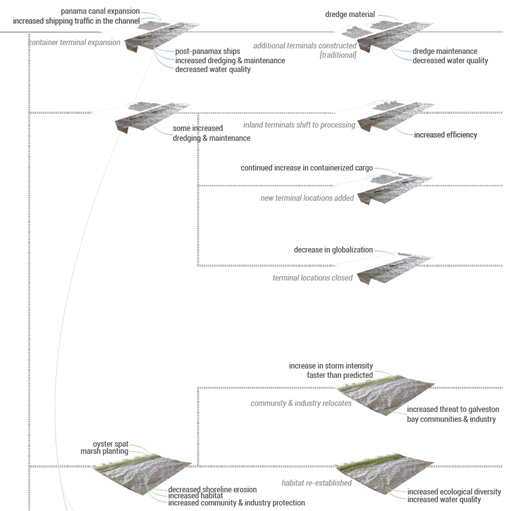

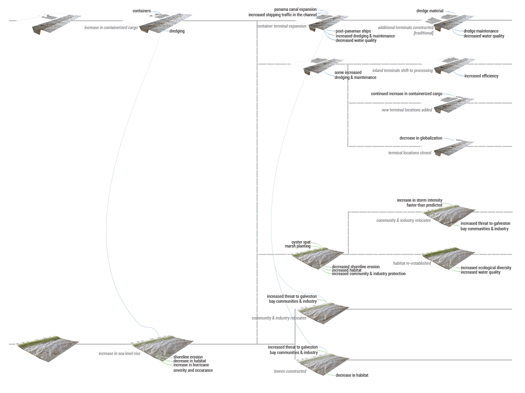

DredgeFest begins with dredging, the linear industrial activity of uplifting sediments and transporting them to new locations. But DredgeFest is about much more than dredging. We believe that dredging is a key component of a much wider cycle of human practices that accelerate, decelerate, transport, and materially alter sediments. We are interested in how the full range of technologies, practices, and organizations operating within that wider cycle collectively alters sedimentary balances, both eroding and generating landscapes.

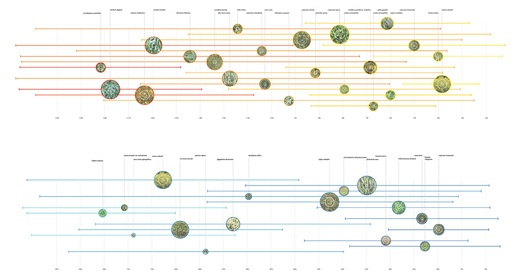

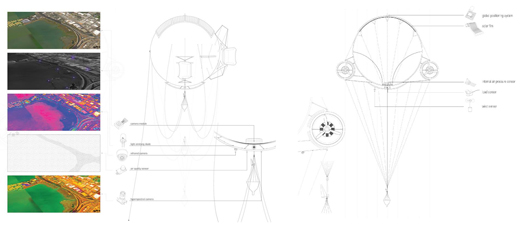

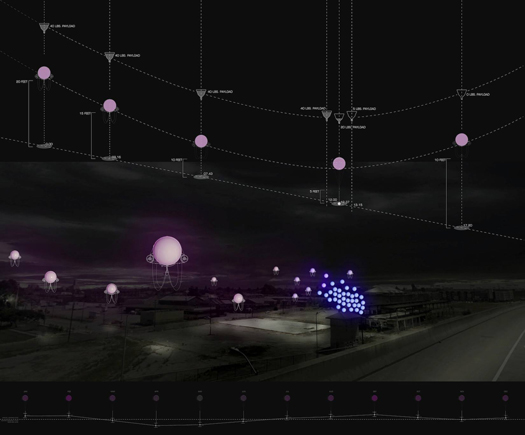

DredgeFest will investigate topics such as dredging methods, sea-level rise, the beneficial uses of dredged material, habitat restoration, marsh terracing, land loss, barrier island reconstruction, invasive species, revetments, spillways, floods, hurricanes, river flow models, advanced geotextiles, landscape robotics, novel ecosystems, feedback cycles, and turbidity curtains. We are curious about the instruments of public participation within the dredge cycle: grassroots organizations, volunteer efforts, environmental health and justice, the political economy of dredge. We are interested in the choreography of sediment along the length of the Mississippi, from Corn Belt farms to the Gulf of Mexico.

Sediment is foundational to Louisiana, playing a more obviously active role in the lives of Louisianans than in the lives of any other American state. We’re excited to hold DredgeFest in Louisiana because we believe Louisiana is living in the future: experiencing the aggregate consequences of human activities for coastal regions sooner and faster than perhaps any other part of the nation, and experimenting with the tools, methods, and practices that will be required to cope with those consequences. We think that more people should be aware of these things, so we are putting on a festival, open to the public.

Schedule

Saturday, January 11-Sunday, January 12

Symposium (New Orleans)

Like the symposium at our previous event, DredgeFest NYC, the symposium at DredgeFest Louisiana will bring together a broad mix of disciplines, corporations, public agencies and organizations in live public conversation, exploring and explaining dredge.

Confirmed symposium participants include:

Sean Burkholder, Assistant Professor of Architecture, University at Buffalo

Travis K. Bost, architectural designer and independent researcher

Richard Campanella, Geographer and Senior Professor of Practice, Tulane University

Bradley Cantrell, Associate Professor and Director of the Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture, Louisiana State University

Sarah Cowles, Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture, The Ohio State University

Andrea Galinski, Strategic Planning, Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority

Stephen Hall, Associate Professor of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, Louisiana State University

Justine Holzman, Lecturer in Landscape Architecture, Louisiana State University

Kees Lokman, Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture, Washington University in St. Louis

Andy Nyman, Professor of Wetland Wildlife Ecology, Louisiana State University

Susan Testroet-Bergeron, Public Outreach Coordinator, Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act

Eugene Turner, Distinguished Research Master and Shell Endowed Chair in Oceanography and Wetlands Studies, Louisiana State University

Robert Twilley, Professor and Executive Director, Louisiana Sea Grant

Karen Westphal, National Audubon Society Louisiana Coastal Initiative and the Paul J Rainey Wildlife Refuge

Clint Willson, Director of Engineering Design and Innovation, the Water Institute of the Gulf

The symposium will be accompanied by an exhibition of research on sedimentary landscapes in South Louisiana conducted by the Coastal Sustainability Studio, Public Lab, and the Dredge Research Collaborative, along with additional work by other independent researchers. It will also be followed by an advance screening of “The Fluid and the Solid”, a documentary film by Ben Mendelsohn and Alex Chohlas-Wood about dredging, the Anthropocene, and the exponential rise of human earth moving.

Monday, January 13-Thursday, January 16

Workshops (Baton Rouge)

Internationally-renowned designers including Smout Allen (Bartlett School of Architecture), Case Brown (P-REX), Alexander Robinson (University of Southern California), Bradley Cantrell (LSU), Richard Hindle (LSU) and Jeff Carney (LSU) will join the Dredge Research Collaborative to lead fast-paced, intensive, and speculative small-group design workshops, running January 13-15. Collectively, the workshops are arranged under the theme of “Dredge Futurism” — future scenarios related to the dredge cycle that may lie outside the investigative scope of official predictive procedures. Three detailed tracks — “Adaptive Devices”, “Hybrid Landscapes”, and “Regional Choreography” — will explore distinctive takes on that dredge futurism. (Full descriptions of the track themes can be found at the DredgeFest website.)

A day-long large-group workshop, led by the DRC and open to all LSU landscape architecture students free of charge, will follow on January 16.

Friday, January 17

Tour (New Orleans)

This bus tour of dredge landscapes in the lower Mississippi River Delta, leaving from New Orleans, will be ticketed, open to the general public, and led by the Dredge Research Collaborative with local experts.

Partners

DredgeFest Louisiana is organized by the Dredge Research Collaborative with assistance from our partners, including the Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture at Louisiana State University, the Coastal Sustainability Studio at Louisiana State University, and Gulf Coast Public Lab.

Series

DredgeFest is a roving event series. The first DredgeFest was held in New York City on September 28 and 29, 2012. DredgeFest NYC was organized in partnership with Studio-X NYC, an arm of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation; sponsored by Arcadis, TenCate, and TWFM Ferry; and featured speakers and content from agencies including the US Army Corps of Engineers, National Park Service, Environmental Protection Agency, and New York City Economic Development Corporation. The event was covered in The Atlantic Monthly, Wired Design, Urban Omnibus,Dredging Today, Scenario Journal, Landscape Architecture Frontiers China, and Landscape Architecture Magazine. A full description and video archive of the event can be found here.