[The following is the text and (a slightly condensed set of) slides from the presentation that Laurel McSherry and I gave at the Drylands Design Conference in late March. The presentation walks through our highly speculative proposal for the reconfiguration of the political geography of the United States to better conform to the spatial distribution of various water resources, such as rivers, aquifers, and man-made infrastructures. I think the proposal is most interesting if it is understood as a speculative update of Powell’s famous 1890 “Map of the Arid Region of the United States, showing Drainage Districts” — with the emphasis being on updating a map, rather than constructing a policy proposal.]

Our work – which we call the commonwealth approach – takes as a starting point Powell’s call to align the nation’s political landscape with its natural resource base ––specifically, the creation of a system of self-governing entities whose boundaries correspond to the natural drainage areas of principal rivers.

Taken together, the five components of our work –– commonwealths, territories, capitals, trans-border regions, and communal aquifers –– reassert the fundamental importance of surface and ground water resources in land planning, and by exploring the reconfiguration of political boundaries, calls out some of the problems with the current system from a water resources point of view.

However, because conditions now are so different than at the time of Powell’s writings, merely redrawing political boundaries to watershed borders still leaves numerous conflicts between political geography and water resource management.

As a provocation, our work illustrates some of the ways that Powell’s framework is inadequate for coping with contemporary problems.

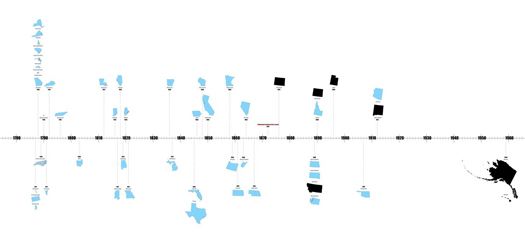

We began by looking at how our nation’s political geography currently relates to water – and quickly discovered a key problem: state boundaries run across and cut up water resources.

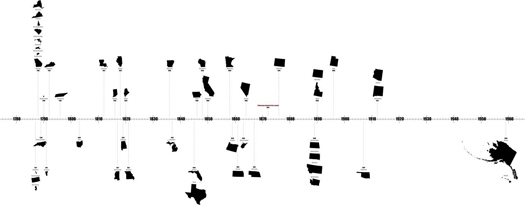

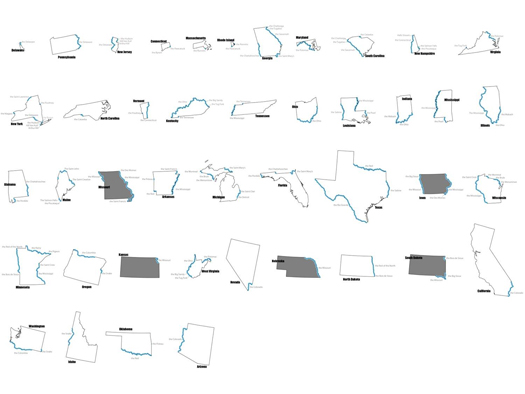

This slide illustrates the 170-year window for the creation of the current 50 states…

…. of which all but 6 utilized rivers or portions of rivers as natural boundaries.

this was due, in part, to the use of rivers in defining the territories from which the states ultimately emerged.

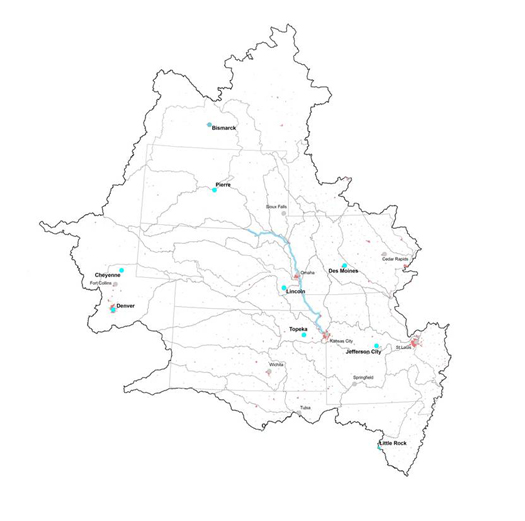

From these forty-four river-bounded states, we selected five (gray, in the image above) –– South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa, and Missouri –– all of whom employ portions of a stretch of the Missouri River, and compared relationships between the their political boundaries and the boundaries of their individual hydrologic subregions.

Because rivers fall in the center of drainage basins, their use as boundaries reinforces a conception of water as a liner resource –– a conception which fails to account for the actual resource geography of water.

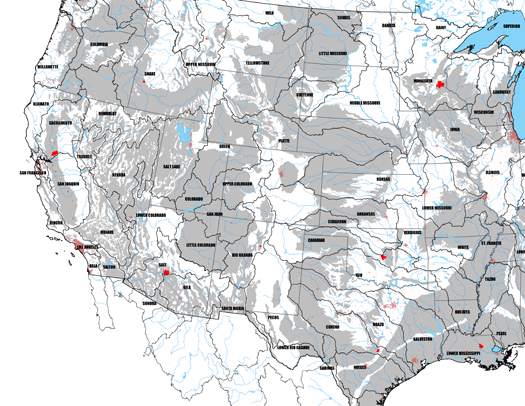

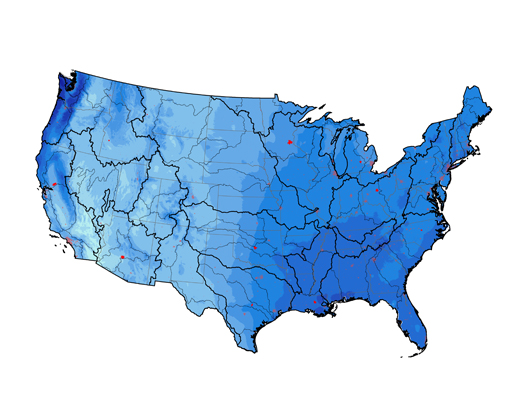

A commonwealth approach –– which aggregates second-order USGS watershed units –– is a first-pass at aligning political geography with the movement of surface water.

Resulting in a configuration of eighty-six commonwealths in the lower forty-eight states.

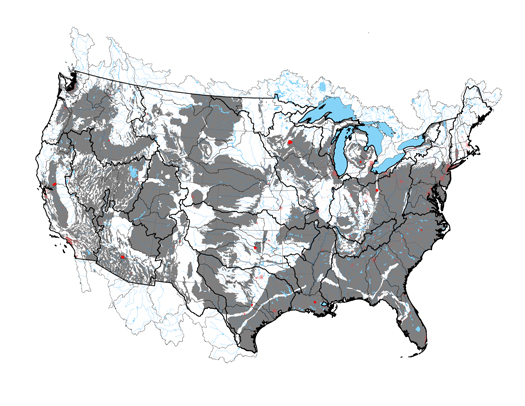

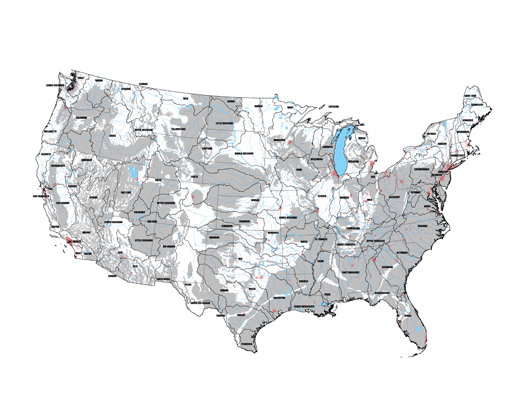

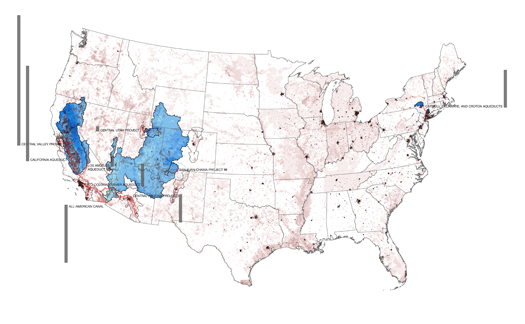

While Powell’s call for commonwealth governance may have gone unheeded, we can expect that he would be most pleased by the degree to which another of his proposals — for the “redemption” of what he called “worthless lands” through agriculture and the engineered transport of water — has been accomplished. Above, a map produced using USGS data which tracks the presence of “watershed modifications” — things like irrigation, dams, and canals — across the United States; what is immediately evident is that watershed modification is a nearly ubiquitous condition.

This condition is produced by a series of infrastructures — wells, reservoirs, dams, aqueducts, canals, pipelines, tunnels, and pumping stations — which, together, create artificial hydrology and, by extension, artificial watersheds.

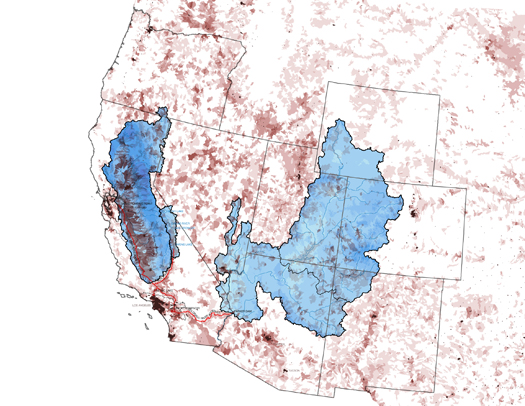

The artificial watershed of Los Angeles, which is constructed primarily by the California, Los Angeles, and Colorado River Aqueducts, provides a particularly instructive example, permitting us to compare an intrajurisdictional transfer (the Los Angeles Aqueduct) with an interjurisdictional transfer (the Colorado River Aqueduct).

The Los Angeles Aqueduct taps the Owens River and Mono Basin, transferring water from one basin to another, but within the same state —

[Photograph: ISS Expedition 28 (NASA Earth Observatory]

at the expense of the health of the donor watershed.

But in the Colorado River Basin — which implicates not just California, but a total of seven American and two Mexican states —

a complex set of agreements and political maneuverings has arisen. Consequently — while we don’t want to oversimplify — it is hard to argue that upstream interests, both human and non-human, are not better represented on the Colorado than the Owens.

Thus we can say that one benefit of political boundaries may be — somewhat counter-intuitively — the difficulties they create.

Both the commonwealths and the larger political entities shown here, the territories, have been strategically drawn to do this.

Commonwealths provide a decentralized political geography, constituting a barrier to centralized strategies for dealing with limited water resources and encouraging instead the relative growth of decentralized tactics — localized, place-specific, and less energy-intensive alternatives.

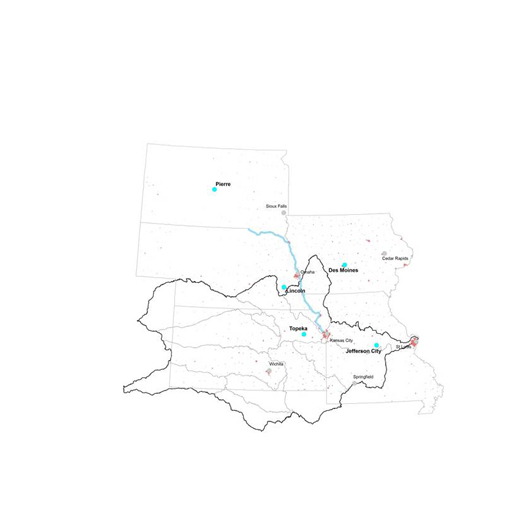

The territories we propose, which are formed by aggregating commonwealths to recognize the boundaries of major river basins, reinforce this effect by recognizing and regulating the special case of interbasin transfer and the enormous impact of infrastructures on Arid Lands hydrology.

(The territorial boundaries derive from the USGS first-level of watershed classification, which divides the nation into twenty geographic areas containing the drainage area of a major river (e.g. the Missouri Region) or the combined drainage areas of a series of rivers (e.g. the Texas-Gulf).

Another problem we see is that of distance and difference. One of the fundamental contentions of our project is that the political geography of the United States — the location of bureaucracies, the subdivision of the nation into smaller units, the position of symbolic and actual power centers like the Capital — biases decision-making. This political geography constitutes an organizational architecture that precedes, constrains, and even produces site architecture.

In particular, the position of the federal government in the District of Columbia, so far east of the 100th Meridian, produces a bias against understanding the full consequences of the aridity of the West.

In response, we propose the distribution of the functions of the federal government to a set of 19 territorial capitals. The driest existing state capital in each territory would become the new territorial capital — reversing this bias without requiring the construction of new capitals.

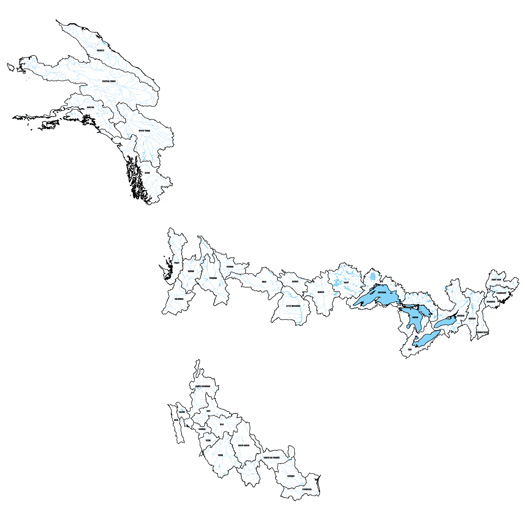

The current political geography also overlooks the fact that watersheds do not stop at international borders. Trans-border regions aggregate North American watershed units into a series of 36 international commonwealths –– requiring, in turn, the creation of trans-national entities to negotiate for the joint interests of America and its contiguous neighbors.

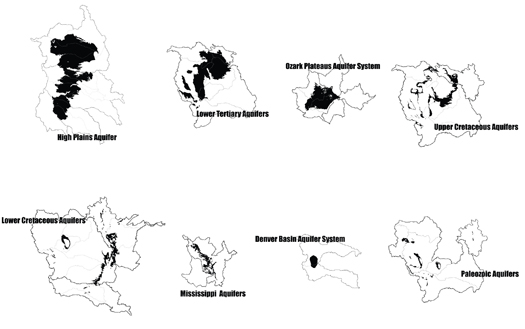

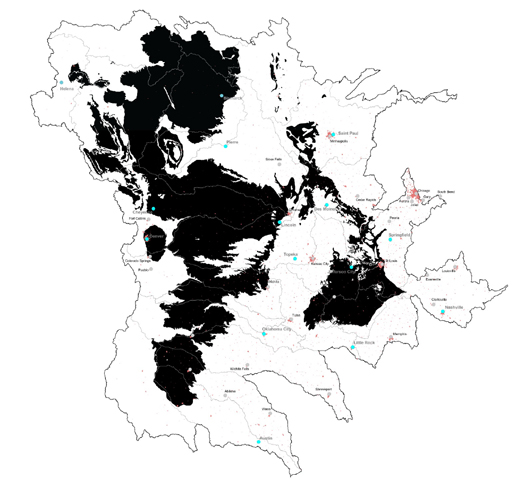

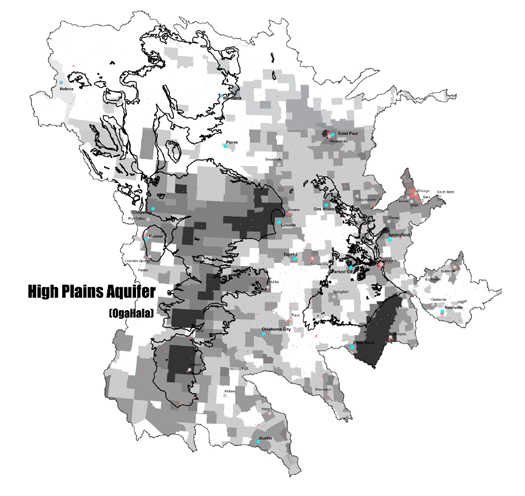

The final dimension of our work –– communal aquifers –– recognizes that subsurface water resources traverse state, national, as well as commonwealth borders.

Returning to the Missouri 5, we learn that redrawing states into commonwealths still leaves conflicts between political geography and water resource management.

In the absence of oversight body or management agreement, these trans-boundary resources (such as the eight communal aquifers illustrated here in this intensity of withdrawals map) will too be subject to the tragedy of the commons.

Our aim with this project, then, has been to construct a series of maps that function as a visual primer in the relationship between hydrology and political geography in the United States. In particular, taking the notion of watershed-based governance — which has existed at least since Powell’s proposal, and which has been implemented in a variety of ways in North America, from agreements like the previously-mentioned Colorado River Compact to agencies like the Columbia River Basin’s Northwest Power and Conservation Council — and indicating some of the other hydro-geographical conditions that contemporary water governance must account for, from artificial watersheds to groundwater withdrawal.

[This proposal was produced with the support of a research award from the Drylands Design Competition as well as Virginia Tech students Becky May and Alex Gonski. Barry Lehrman‘s assistance was also invaluable in researching artificial watersheds. The conference and the competition were both organized by the Arid Lands Institute at Woodbury University, whose directors are Peter and Hadley Arnold.]

![20120227_Watershed_Mods_Number [Converted]](http://m.ammoth.us/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/21_small.jpg)

Love this! Infrastructural design as political landscape….

Thanks, Nam.

Very nicely presented Rob.