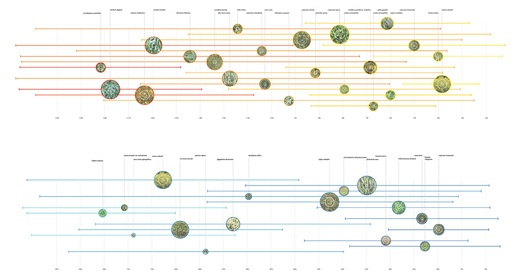

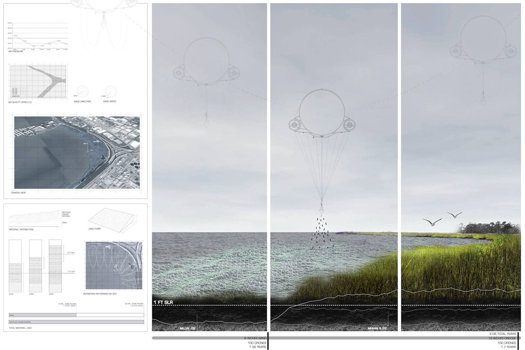

[Diagram describing the “interaction between a script to generate a planting plan and data generated from the soil and salinity analyses”, from Philip Belesky’s research project “Processes and Processors”.]

I recently encountered the work of Philip Belesky, a PhD candidate at RMIT’s Spatial Information Architecture Laboratory, who is thinking very interesting thoughts about the role of computation and programming in landscape design.

While this post is primarily going to interact with a few key points from Belesky’s recent post on Julian Raxworthy’s recently-completed thesis (as this is a blog post, it seems appropriate that things get highly referential very quickly), it’s worth introducing Belesky’s work via his contribution to Kerb 21, which was entitled “Adapting Computation to Adapting Landscapes”.

In it Belesky argues against the currently prevailing paradigm for computational design in landscape architecture…

The current canon of computational design techniques is distinctly architectural, aimed at generating and optimising form so that architects can better design complex geometries, complex structures, and complex details. Looking to the few landscape-focused practitioners who do use computational tools, we see designs that typically feature branching, flowing, twisted, folding, and fracturing surface geometries. Here, the formalisms common to the architectural avant-garde have been appropriated by way of a 90 degree rotation: façades turned to become fields.

…argues instead for the deployment of computational techniques as augments to “intuition and analysis” within the design process, through the simulation of landscape processes…

Unlike plans or diagrams, a computationally-defined design emerges from a series of generative rules that form a dynamic system. By creating rules that account for the temporality, uncertainty, and dynamism of landscape systems we can begin to make these phenomena truly operative within the design process. A design for a waterfront could be seamlessly tested against simulations of the hydrological systems that govern tidal flushing, coastal erosion, sea level rises, and storm surges. Planting plans could automatically match particular species to local changes in substrate, grade, saturation, and shading, while maintaining a cohesive composition that maintains ecological diversity and aesthetic effects.

…and speculates (rightly, I believe) that this deployment will require “computational techniques that focus on landscape systems”:

In the same way that architects have created tools to simulate how structural, solar, and thermal systems operate, we must develop tools that make hydrological, ecological, and other landscape systems active within the design process. These tools exist within scientific research and specialised software. The challenge is to adapt these tools by integrating their capabilities into the computer-aided design programs that landscape architects already use.

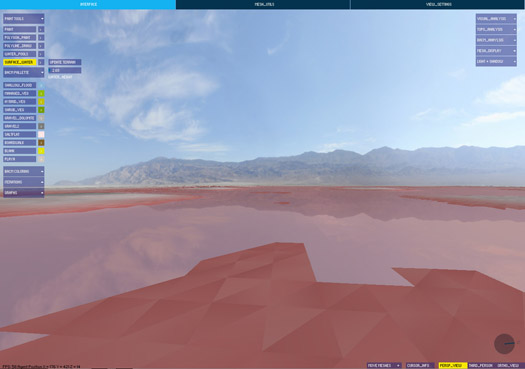

(This, I should note, is remarkably similar to how Alex Robinson explained the intentions and potential of the bespoke landscape visualization and analysis tool package he presented during the workshops we organized for DredgeFest Louisiana. Robinson has been developing that set of tools for a specific project, a collaboration with the Army Corps of Engineers at California’s dry Owens Lake; I immediately wanted to see the tools recontextualized as first steps towards a set of geographically-agnostic instruments, a first draft of a true landscape information modeling package.)

[Screenshots from software produced for the Landscape Morphology Lab’s Rapid Landscape Prototyping Machine project.]

Having introduced the general pattern of Belesky’s work (hopefully without misrepresenting him), on to the primary subject of this post, Belesky’s recent post “Pruned Precedents and Growing Potentials”. That post (planned as the first in a series, all of which will be worth reading if this first instalment is any indication) reads Julian Raxworthy’s thesis, “Novelty in the Entropic Landscape: Landscape architecture, gardening, and change”, in light of Belesky’s own interest in the potential of computational design, refocused on “the temporality, uncertainty, and dynamism of landscape systems”.

I am now encouraging you to read the actual text of Belesky’s post. When you return, I’ll quickly say four things about Belesky’s reading of Raxworthy.

emergence

First, I’d like to record my strong agreement (along with Belesky) with Raxworthy’s critique of the products of the influence of the “Process Discourse” (as Raxworthy terms it) on architectural design. I’ll quote the same portion of Raxworthy that Belesky does:

This new disciplinary proximity is most evident in a fascination with change and time, expressed in terms such as “dynamism”, “mobility”, “process” and “flexibility” that have featured prominently in publishing in both areas since the mid-1990s. This body of thinking and practice I identify as the “Process Discourse”…

…The rise of the process discourse has seen the adoption of ecological models of process, and their generalisation into algorithms, which are now incorporated into architectural-design generation process in order to give designs some of the qualities of dynamism that natural systems possess. Architectural genres such as parametricism and datascape work to model dynamic landscape forces in the design-generation process, but do not change when made as actual structures in reality. I argue in this dissertation that by simulating change, projects underpinned/informed by the process discourse do not exhibit the key philosophical property of change, which is the spontaneous emergence of novelties. This property is recognised in the language used by the process discourse by terms such as “emergence”, but is effectively ignored in the simulatory models of architectural form.

That’s accurate and well-put. (I think I was groping towards a similar critique in the early days of mammoth, though I never arrived at anything nearly as elegant or systematic as Raxworthy’s critique.)

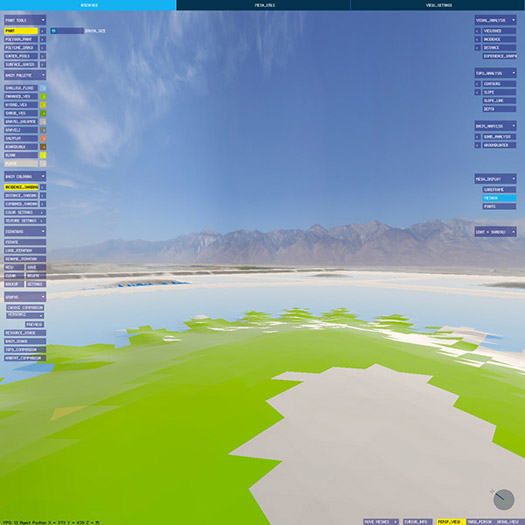

[Diagram and site photography from PEG Office of Landscape + Architecture’s “Edaphic Effects”, a gorgeously exact/inexact instance of site-specific “off-label uses for erosion control products”, to quote Sarah Cowles. “Exact/inexact” because it is both an instance of tightly controlled variation in pattern and an instance of the imprecision of the application necessitated by the execution of that pattern not just in material, but in landscape material. That inexactness is perhaps one of the most interesting differences between digital morphogenesis in landscape and most digital morphogenesis in architecture, and hopefully a space that future computational landscape architects will more fully exploit.]

pattern and process

As Belesky moves into outlining points where he diverges from Raxworthy, he makes a brief comment that I find illuminating when placed against arguments from Karen M’Closkey’s recent work on pattern and process. Discussing Raxworthy’s criticism of the tendency of the work like that of the AA’s Landscape Urbanism program to treat data and process as the generator of a logic for a new “short-term reconfiguration” of landscape that is “largely static and inflexible”, “impos[ing] a new equilibrium upon the landscape”, Belesky argues that digital simulation is nonetheless capable of contributing to a design process that admits “the slow and gradual trajectories of landscape systems”:

“…improving those tools to better take account for temporal processes would probably discourage a tabula rasa approach by helping designers to work with — rather than supersede — the systems present on-site.”

This helps me articulate a discomfort I had when reading M’Closkey’s recent contribution to JoLA, “Synthetic Patterns”. The article is generally excellent, and I am very much appreciative of the overall intention and results of M’Closkey’s efforts to recover a role for pattern-making in landscape architecture. (The core of M’Closkey’s argument is roughly that patterns have the potential to organize site processes while “bind[ing] together oppositional categories that seem to plague discussions in landscape architecture—system versus composition, representation versus performance, matter versus symbol, vision (distance) versus immersion (multi-sensory)”.) Unfortunately, M’Closkey ends the article in an excessively cautious way, associating the efficacy of the kind of digitally-generated pattern she argues for primarily with their capacity to organize post-industrial sites:

“To design with nature today, we should not attempt to camouflage the fact of our manufactured sites—sites that must be remade in order to support new uses and habitat. There is no inevitable form, or formula, for dealing with such sites, so we need not rely on standardized, engineered solutions for doing so.”1

1I should note that I am reading M’Closkey’s text in parallel with the video from her presentation at the recent Datascapes symposium at LSU, where she makes this point at least as explicitly.

2That said, I think this precise opposition is present in this neat formulation only in M’Closkey’s rhetoric, which suggests that it is possible I am making too much of it. In her built work, like the “Edaphic Effects” project shown above, pattern serves to mediate between extant systems and the designer’s intent, as evidenced by the use of “parametric software to visualize existing and redirected water flow patterns”.

I find this an unfortunate turn both because it elides the value and utility of the natures already present on such sites and (this is where I think Belesky’s point is useful) because it radically limits the scope of the argument for pattern that M’Closkey is making. It seems to me that the promise of digital pattern-making is instead the opportunity to move beyond the kind of relatively simplistic patterns that analog pattern-making at the scale of the capital project is confined to (e.g. the Peter Walker projects M’Closkey references in the article) and, instead, toward more sophisticated pattern-making techniques with rulesets that take into account simulations of the interactions of pattern and process. This would, as Belesky argues, “discourage a tabula rasa approach by helping designers to work with… the systems present on-site”. Viewed in that light, hinging an argument for the role of pattern on the explicit selection of ‘blank’ landscape canvases seems precisely the opposite of the best rhetorical and operational strategies2.

on the limits of simulation

Responding to Belesky on his own blog, Raxworthy reiterates his argument:

“In terms of argument, I acknowledge his points completely in clarifying what simulations can do, and particularly his gentle reproach that there is more recent work from Penn that are better simulations: what can I say, I wrote that part of the thesis 10 years ago, and kept it, because the basic argument remains true that simulating growth and real growth are different. While it may be interesting and worthy to pursue more accurate and effective models of simulation, their focus will always be on their own internal complexity and growth. Which is fine if your site is the interior digital milieu. But if it’s the world, then I argue (a bit polemically here, I grant, but it’s the nature of my blog) you are chasing your tail, since modeling will always by definition lag behind the real.”

In general, I think I’m agnostic about the implications of the truth (or truism, which is the issue) that Raxworthy notes: yes, simulations by definition are incomplete models of the real; but this hardly answers the question of whether they are a useful tool for making landscapes in specific instances. If forced to venture a response, I would be probably offer something like: sometimes they are very useful and other times they are worrisomely misleading or unpredictably wrong, with the skill lying in the negotiation between and evaluation of those two possibilities. Consequently, I’m attracted to schematics for that negotiation, like this from Jamie Vanucchi’s landscape modeling studio tumblr.

Similarly, I’m also in complete agreement with Brian Davis’s argument for a multifaceted approach to landscape information modeling in his “Landscapes and Instruments”:

“[Arguments for the inclusion of landscape components in BIM software platforms are compelling] but ignore a set of important issues related to landscape practice that spring from the realization that architecture and landscape are different mediums. While sharing many concepts, materials, working methodologies, and histories, there is no reason to suggest that our representational, investigative, and project delivery tools should be the same, or should have more in common than do landscape architecture and forestry, or sedimentary geology. In fact, I believe my work provides evidence to the contrary. Initial results thus far point away from trying to find a single computational environment for landscape representation, especially one built on the conceit of abstract, limitless space. Instead, it is the process of working between modes- comparing them, interrogating the assumptions and limitations of each- that has been most useful and revelatory in my work. This suggests that in addition to lobbying for the inclusion of landscape as a subset in the development of BIM technology, we should be learning from, appropriating, and synthesizing the representational models of ecologists, civil engineers, and sedimentary geologists to construct methods of landscape information modeling.”

tendency, feedback, and responsive landscapes

Ultimately, Raxworthy’s thesis arrives at a two-pronged response to the question of how landscape architecture can encourage and manipulate the emergence of genuine novelty. The first prong is “tendency”, which Raxworthy defines as “a way of thinking about the design process that recognises that design is a form-making process inherently tied to a prediction of an end, or later state, but where novelty is encouraged to develop over time”. The second is feedback, or “continuing, real-time involvement in a process … when the output of the process is fed back into another iteration of the process as an input”, which Raxworthy rightly associates with the role of the gardener. (One reason that I enjoy Raxworthy’s work is that I see gardening as one of the key disciplinary inheritances of landscape architecture, and appreciate seeing it explored in a non-reactionary context.)

Reacting to these two prongs, Belesky focuses on the first, tendency, arguing that “the use of computation to examine ‘tendencies’ in the design process seems promising”. This makes sense, as this is precisely what his earlier article in Kerb suggested needs to be happen3.

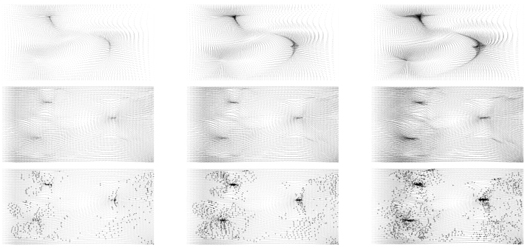

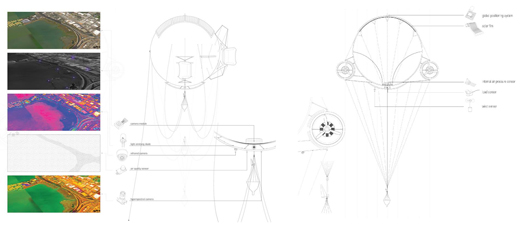

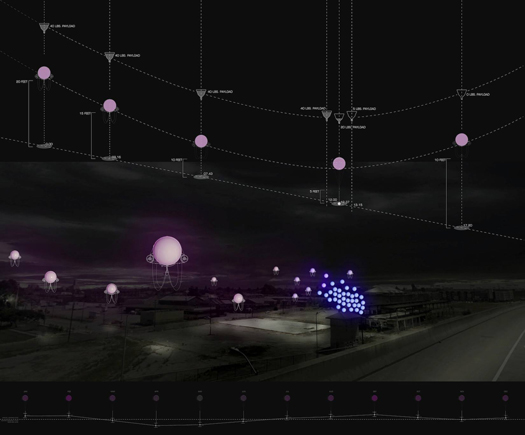

[Images from “strATA”, a proposal to use “remote environmental sensing and large-scale climate models” to “build a feedback loop of sensing, reacting, and adaptation” toward designed incremental sedimentary deposition. “strATA” was produced by Lydia Gikas and Matt Rossbach in Bradley Cantrell and Justine Holzman’s Fall 2013 studio at LSU.]

However, I think his quick concession that the second prong is not a promising direction for digital landscape architecture is, in fact, far too quick:

“Unless environmental sensors become widespread and embedded, there isn’t much opportunity for computational tools to engage with real-time feedback.”

Doesn’t the opening conditional here at least have a strong likelihood of being false in the near-future? Sensors are cheap, getting cheaper, and being deployed in a wide variety of environmental uses that read like science fiction: sedimentary particle trackers, autonomous underwater monitoring robot swarms, Plants employed as SEnsing Devices, the overlap of remote sensing and virtual fencing. Rather than “not much opportunity”, this seems an extremely promising field of study, if technologically volatile. (Bradley Cantrell‘s work is one obvious example of such exploration.)

Now let’s all go read Orrin Pilkey’s Useless Arithmetic while doing exercises from The Nature of Code.

Interesting discussion Rob, and great to be referred to and introduced to your blog.

Reading this post, and your response to my take on the process discourse, there is another section where I note, roughly, that ecology has become denatured and machinic and that this take on ecology removes the fact that ecology is specific not general.In other words there is no longer any ecology in ecology. For me this is a turn from the world and a loss of the real potential of ecology as a way of understanding the world, whereas the machinic version of ecology models the world and then responds to this model. Add this is precisely what the problem of economics has been: it has created a separate, disconnected world that nonetheless effects the world, but does not, as yet in the growth paradigm, get feed back from it.

a more radical, and for me more interesting paradigm is that which I remember from a lecture by Brian Massumi around the time of Parables of the Virtual, where he seemed to argue that we needed to derive a physics from the conditions of the virtual while working in the machine, that was separate from the world, since it was its own world. The odd discrepancy of programs like Second Life, and books like Otherland, that fictionalise the virtual, is that their simulations are real world fantasies, not digital realities. Here I am reminded of Bateson and his epistemological rigor, and I would urge people to read Mind and Nature to get a sense of how we need to be careful that one view deos not spill into or make claims to the other when they are nit actually linked.

Instead, I would argue that some fundamental landscape thinking concepts operate in an interesting correlate in the digital space: organisation, object/field, centre/periphery, emergence, qualities, etc. All the stuff that LU loved but which it kept simply being rhetorical about in the world, can be worked with in a rational and logically consistent way in the digital space, where a landscape sensibility and systemic thought process can be a useful adjunct to speculating that space.