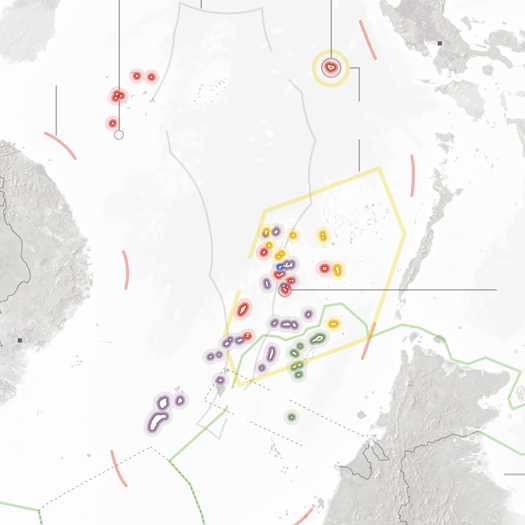

[The Spratly Islands]

A series of reports from the Philippine government recently emerged and came to the attention of the international press, describing a series of semi-clandestine island-building operations undertaken by the Chinese government in the South China Sea. (To quote a local fishing contractor who works in the vicinity: “there was this huge Chinese ship sucking sand and rocks from one end of the ocean and blasting it to the other side using a tube”.) These acts of territorial reclamation are being undertaken with the intent of enforcing Chinese claims to the vigorously disputed — and likely resource-rich — waters in and around the set of low-lying islands, reefs, and atolls known internationally as the Spratly Islands, as the New York Times reports:

Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel scolded China for “land reclamation activities at multiple locations” in the South China Sea at a contentious security conference in Singapore in late May.

Critics say the islands will allow China to install better surveillance technology and resupply stations for government vessels. Some analysts say the Chinese military is eyeing a perch in the Spratlys as part of a long-term strategy of power projection across the Western Pacific.

Perhaps just as important, the new islands could allow China to claim it has an exclusive economic zone within 200 nautical miles of each island, which is defined in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The Philippines has argued at an international tribunal that China occupies only rocks and reefs and not true islands that qualify for economic zones.

“By creating the appearance of an island, China may be seeking to strengthen the merits of its claims,” said M. Taylor Fravel, a political scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

[A portion of a map of competing territorial claims in the South China Sea produced by Derek Watkins for the New York Times; view the full map here.]

[The Utrecht, one of Dutch dredging conglomerate Van Oord’s fleet.]

Take as background both this example of the aggressive assertion of territorial influence by a nation-state through dredging and the general anticipation of the increasing economic importance of seabed mining, offshore drilling, and other economic exploitations of oceanic territories. It is not difficult to envision dredge developed as a new frontier in international conflict, where oceanic international borders are rapidly re-shaped by the construction and counter-construction of island chains and atoll formations, all strategically deployed to extend and compress bands of territorial waters, in a game of Go played by foreign ministers releasing escalating and conflicting bids to dredging contractors. (China offers Boskalis $600 million; Vietnam counters with $700; the Philippines derails their bid at the last minute with a promise of a cut of oil rights for the corporation, prompting China and Vietnam to covertly deploy a fleet of pirate dredgers, who siphon sand from the new Filipino island at night.)

Or, speaking of those dredging contractors, given the enormous role of corporations in the global restructuring of coastlines via marine engineering and the increasing function of transnational corporations as modern analogues to medieval city-states1, to imagine a rogue dredging contractor secretly designing its fleet assignments to shuffle vessels to some distant Pacific outpost, where it is building a new island for itself, beyond the reach of any nation-state.

Or, post-apocalyptically (or simply a century from now), Waterworld meets Flood via Dredging Today, post-peak sand.