The following is a study of a hypothetical water farming infrastructure for the arid city of Luanda, Angola; using fog harvesting nets with varying capabilities.

Luanda, the fastest growing city in the world, is desperately short of clean water. Only one in six Luandan households has running water, forcing most of the inhabitants of the musseques (the vast slums that constitute the majority of Luanda’s land area) to depend on contaminated water brought by truck from rivers hours north and south of the city. The price of water in the musseques can be as high as 12 cents a gallon, a huge burden on a populace which lives on an average of $2 per person per day. In 2006, the worst African cholera epidemic in a decade devastated the musseques, killing 1600, spread by contaminated drinking water as well as contact with sewage.

What if water, already inextricable from agricultural farming processes, was itself farmed? Beyond the direct benefits a renewable source of fresh, clean water would provide Luanda, farming water seeds the city with potential. By establishing an infrastructure to effect the farming of water, one may farm landscapes, societies, production: a city.

Farming water in parched terrain seems paradoxical, but an established process for doing so already exists: fog farming. Like most forms of farming, fog farming can be seen as a special instance of infrastructure and, as an infrastructure, it has both direct and indirect effects: it is directly responsible for condensing and collecting airborne moisture; but it also has many indirect effects on the growth and health of the urban system. The fundamental inquiry of our project is a unique treatment of infrastructure, considering not just how its programmed function can enable positive development of some urban condition, but how the thing in itself, the system which enables that function, can have other, non-function-related (indirect) effects — and how they can be understood and utilized.

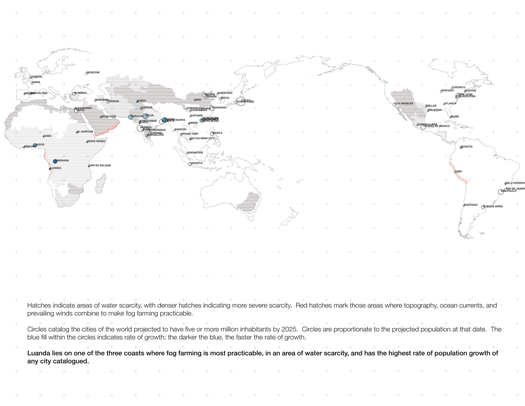

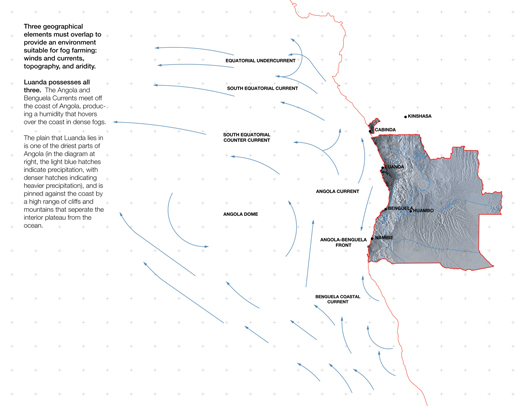

Before exploring those indirect effects, though, a brief description of the techniques and requirements for fog farming may be helpful. This technology has been explored for several decades as a means to obtain potable water in arid environments, though until now it has been confined to rural locales, owing to problems with airborne particulate pollution. A typical apparatus consists of a nylon or polypropylene mesh, at least a meter or two square, stretched across a metal or plastic frame, with condensed moisture dripping down the mesh into a collection pipe at the bottom of the net. The basic necessary conditions for the deployment of such an apparatus are an arid environment and strong fog. Such fogs are found primarily along particular ocean coasts (the Pacific coasts of Chile and Peru, the Atlantic Coasts of Namibia and Angola, or the Indian coast of the Arabian peninsula) where certain ocean currents produce atmospheric moisture which is then confined and concentrated by mountains.

Luanda is by far the largest city in the world in which fog farming is practicable, as it is projected to jump from a current population of four million to over eight million by 2025. Though Luanda experiences something of a rainy season between March and April, for most of the year precipitation is nearly absent — averaging 0 millimeters/month from June to August — as the Benguela and Angola currents of the Atlantic Ocean combine to prevent the humid air from condensing into rain. This combination of humidity, aridity, and explosive population growth creates a situation uniquely suited to an experiment in urban fog farming.

Fog farming has the direct potential to meet this need for potable water; but an investigation of this form of farming can also reveal important things about the role of infrastructures in urbanism, if we consider its indirect effects. We believe that this move — the equal valuation of indirect effects and direct effects — is essential to the development of an alternative modernist urbanism, for several reasons:

A We argue (like many others have, particularly in the past decade or two) that the modernist planning movement has run its course; has been exposed as insufficiently flexible to react to the flux that characterizes a vital urban condition. This is because modernist urbanism was concerned primarily with controlling the city, which inevitably produced conflict between the dynamic nature of the urban system and the static nature of the designer’s reality.

B We also take as a starting point the inadequacy of some alternate proposals, particularly those such as new urbanism and parametricism, that propose an alternate set of forms to modernism while failing to account for the fact that it was the overreliance on formalism itself — on the controlled expression of the rationality of the designer — that made modernist planning unable to cope with the reality of the urban condition.

C We suggest that infrastructure is an appropriate object of design for the urbanist, the architect, and the landscape architect, as infrastructure can be embedded with some characteristics that provide definition (a means for the urbanist to have influence on the direction of change), as well as characteristics that permit appropriation by inhabitants of the urban system. In other words, an infrastructure can withstand appropriation while remaining coherent as an intervention.

Fog farming, then, can only be fully understood as an urban intervention if it is understood as performing ‘infrastructurally’ — as having effects on the urban system that extend far beyond the direct or spatial, to the alteration of streams and flows — liquid, capital, human, traffic, and so on. Thus we have sought not merely to provide a form of farming that meets a need for water, but also to understand how, in placing an infrastructure that would meet that need, we might also alter the streams and flows of the urban system for the better.

Consequently, the infrastructure we have developed is unified by its fundamental nature as a system for farming airborne moisture, but diversified in architecture, deployment, funding, distribution, and ownership, as the modification of each of those characteristics affects its interaction with the city.

Furthermore, we remain extremely sensitive to the fact that one of difficulties of working (as a designer) in a city like Luanda is that the city government cannot always be relied upon to act in the interests of the poorest inhabitants. Indeed, even we — seeking as designers to act in ways that we perceive as beneficial those who live in the musseques — are likely (if not certain) to be mistaken at times about what will benefit the musseques. And so we have varied the degree of control embedded in the infrastructure, allowing it to be more rigid in the wealthier portions of the city (where citizens have access to the levers of government) and relinquishing nearly all control in the poorest regions. Some functions, which we hope will remain uncontroversially beneficial, are embedded in the nature of the infrastructure we make available (most essentially, that it cultivates useable water from fog).

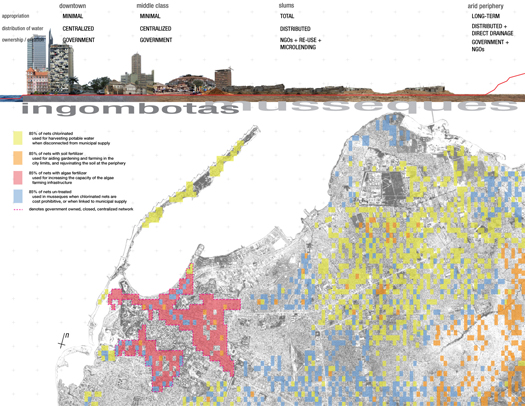

To these ends, we propose four basic forms for fog farming in Luanda (though the boundaries between forms would exist more as gradients than as hard delineations):

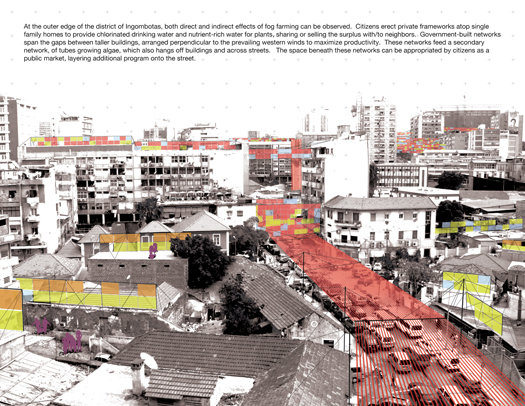

1 In the central districts of the city, particularly Ingombotas, a highly formal farming architecture appears, spanning the gaps between buildings and hanging off of scaffolding over streets, providing water treated with nutrients for the benefit of a system of tubes growing algae, which is in turn harvested at processing plants to make biodiesel. The profits from an industry with a fixed end-date (the oil industry) can be invested to build an infrastructure that will meet the energy needs of Luanda far past that end-date. The distribution of this water is centralized; it is a striated, non-rhizomatic network. It would be government funded, with the intention that economies of scale (resulting from the erection of this network) would drive down the cost for building future fog networks in lower income areas of the city.

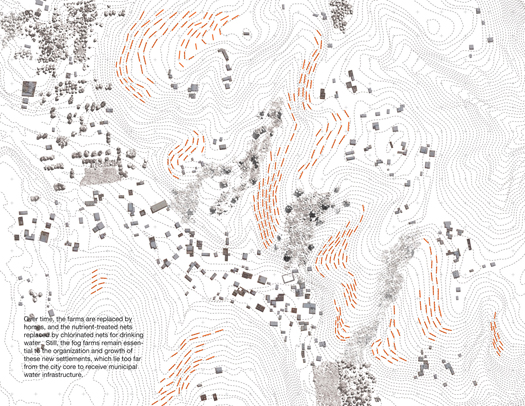

2 Middle class suburbs, which ring the central districts, would also receive investment from the government and see an interface arise between the municipal water system and the fog farming infrastructure, though some of the water supply generated there would be diverted to growing personal gardens and other vegetative uses.

3 In the musseques, a combination of NGOs and microlending practices would fund the development of an infrastructure, while the deployment would be at the whim of the citizens, who stand to benefit from the income generated by new sources of water. Appropriation by the community would be nearly total, while the benefits of the infrastructure would accrue entirely to the local communities. Distribution of the water would be completely local and decentralized, disconnected from the municipal supply and its filtration. Because of this, we propose nets treated with a slowly-released store of chlorine whenever affordable, with untreated nets supplementing the supply.

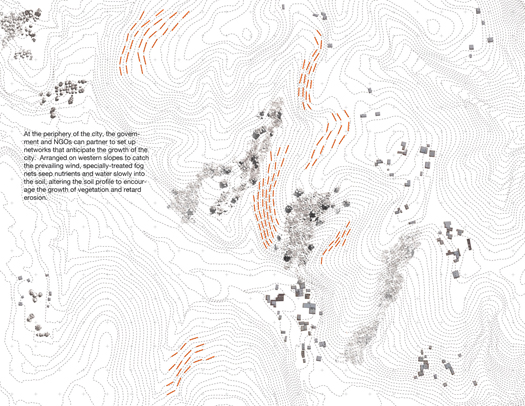

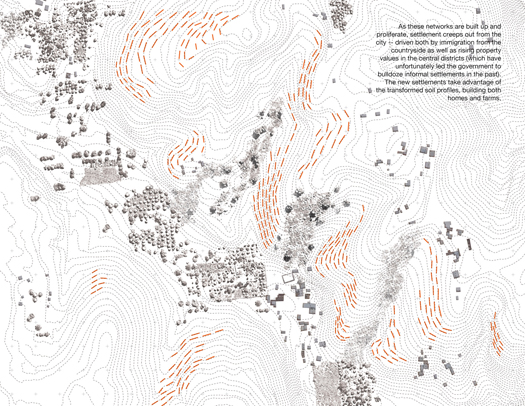

4 On the arid periphery of the city, fog farming would serve to seed the future of the city. Though the practice is deplorable, it is unlikely that the government will stop clearing informal settlements in the center of the city, so the periphery will likely continue to swell with a constant mixture of slum dwellers expelled from their homes and new arrivals from the hinterlands of Angola. Expanses farmed for fog would be gradually impregnated with nutrient-rich water, cutting down on dust storms, prompting the growth of farms and eventually settlements based around this infrastructure. Through farming water, we farm landscape, farm city, farm future communities.

a statistical index of luandan fog farming:

83% the percentage of Luandan households without running water

12 cents the price per gallon of water in the musseques of Luanda

0 the average monthly precipitation in Luanda from June to August

6% the current yearly average growth of Luanda

4.8% the current average growth of the next fastest growing major city in the world, Kinshasa

4,000,000 the population of Luanda in 2007

8,200,000 the project population of Luanda in 2025

12.9 L the projected average amount of water collected by a square meter of fog net in one day

244 the number of days it would take to recoup the cost, including both materials and installation, of a square meter of fog net at the current price per gallon of water in the musseques

1,200,000 the amount of water trucked into Luanda every day from the Bengo and Cuanza rivers

$35,152,969 the estimated cost of replacing the volume of water brought using trucks from the river with water from fog farming

$100 the estimated cost of a square meter of fog net, including materials and installation

2/3 the number of Angolans living on less than $2/day

450 the number of tanker trucks that travel from the rivers to Luanda every day

1,600 the number of Luandans killed by a major cholera epidemic, due to contaminated water, in 2006

[…] BKRT Essay: on fog nets and cities – mammoth"The following is a study of a hypothetical water farming infrastructure for the arid city of Luanda, Angola; using fog harvesting nets with varying capabilities"(tags:eco tech ) « Me By Zo […]

Too bad it’s intractable, cites nothing, lacks credentials (even the author’s citation is blog-local), and contains images with text so small it -should have been- greeked. It’s just illegible, and there is neither alt text nor an accessible SVG or Flash (BTW haven’t seen accessibility tools for that, just claims) graphics. I hope a feral oxygen hound visits you on your freshness farm and tears you a new exegesis.

Steve, thanks for a proper welcoming to the internet. Some of the issues you list above (small images / text, no citations) should no longer be so upon it’s publication in a glossy next winter, but likely much will remain for you to be bitter about. Be sure to stick around and keep us honest.

While I don’t think “intractable” and “exegesis” mean exactly what Steve appears to think they mean (as best as I can tell from my, umm, exegesis of his comment), I think he’s right about at least one thing: we do need to provide a link to the images at full resolution. Images intended to be read at 8.5×11 are less than clear at 525px wide.

Cities grow where there are geographical advantages (location, transport corridors) and resources (farmland, water). It is reasonable to ask why Luanda is growing, and whether the artificial factors that outweigh its disadvantages should be addressed, halting this unsustainable expansion.

I am not advocating a reliance on the ‘natural’ constraints to unsustainable growth – war and disease – but I fear that water riots and cholera will continue to be a feature of a city where extra water infrastructure never quite keeps up with population growth.

In short, the problem isn’t water, it’s people: and water shortages are a symptom which will not be cured without seeking humane ways of reducing the population in Luanda to sustainable levels.

Nile, thanks for your thoughts. It’s certainly true that the population of Luanda is currently unsustainable, and will get even more so if things remain unchanged. However, I disagree with your assertion that the only solution Luanda has available is to limit its population size.

The amount of population a city can maintain has always been linked to technology and infrastructural sophistication. It was farming technology which caused the development of cities in the first place. Sewage technology resolved for London many of the sanitation issues now felt by Luanda, allowing that city grow while sustaining a previously unsustainable population. I was in NYC yesterday, and it would have been a horrible experience if that city only had Luandan technology.

Your concern that the growth of Luanda will always outpace it’s water infrastructure (among others) is vital however, and I don’t have an answer for it. But I do believe an answer exists, and it may require the sort of temporary population tempering you advocate to allow population and technology to grow in synch; with the minimum human suffering possible.

Nile, I think the issues you raise are very important, but I have to disagree.

(1) While the intense concentration of people in a given location (such as Luanda) can produce problems, the people themselves are not and are never the problem. I think this is an extremely important distinction: one phrasing (“people are the problem”) implies that getting rid of people is the solution (an act of incredible rhetorical violence which is capable of producing actual violence), while the other (“the concentration of people can produce problems”) allows us to admit that we need solutions without being cavalier about the humanity of the people whom we speak of. I don’t want to assume that you mean the former, but I want to make this point regardless of what you meant.

(2) That said, I’m not sure that “should Luanda grow” is a very important question for architects to address, as it would be purely rhetorical. What I mean is that, even though our study of fog farming is entirely hypothetical, it is the sort of hypothetical project which could be realized through architectural practice: these nets could be refined in design, could be built, could be funded through the mixture of means we have suggested, and could be placed within the city by the mixture of actors we have suggested. They interact with a problem — the lack of clean water — which is real and suggest a means by which architectural practice could address the problem. While there may or may not be more people concentrated in Luanda than the ecology of the region can support, it is hard for me to see how overconcentration is a problem which landscape/architecture could address.

(3) Finally, I think Stephen is right that it is very difficult to assert that Luanda is too large when its infrastructure is so clearly lacking in ways which we have the technological tools to address. When I see a photo of a street in the musseques serving as both sewer and street, I don’t think: “too many people!” — I think: “this is a problem which improvements in infrastructure could address”. I’ll certainly allow that its possible that, even with the deployment of every technological tool at our disposal, Luanda still would not be able to provide adequately for the needs of its population — but I don’t think we have anything like the kind of information necessary to say that definitively. Whereas we do have the information to say “if we made these improvements to the infrastructure of the city, we would improve the lives of the inhabitants in these ways”. Which is enough for me.

[…] I have a number of minor quibbles with Galloway’s article (for instance: I don’t think I’d agree that there is no ecological reason to promote density, though I would agree that the dry formula “density=good, sprawl=bad” is simplistic), but he does a commendable job of teasing out two important and contradictorary threads, which are that the informal city, whether in the developing or the developed world, is (a) pregnant with possibility and (b) problematic and in need of intervention. Becker and I would, obviously, like to think that it is exactly those contradictorary threads we were addressing with our recent project/essay on fog farming in Luanda. […]

[…] rain events toward certain building types – where, as mammoth’s own earlier paper about fog farming suggests, “fog nets” might capture a new water source for the […]

[…] such as in Brennen’s SuperNeutral proposal? We tried to deal with this question in our proposal for a Luandan fog farming infrastructure. While undoubtedly still an underdeveloped component of […]

[…] also mammoth’s own sloppily documented entry to [bracket]] This entry was written by rholmes, posted on July 31, 2009 at 12:27 pm, filed under […]

[…] which I think I’m being fair in saying that most westerners have never heard of (when we made this map, which shows only cities project to have over 5 million people by 2025, for our entry to the […]

[…] scale in literal fog farms, like a botanical version of the urban fog farms that mammoth has proposed elsewhere? Or invasive submerged aquatic vegetation genetically programmed to assemble themselves into […]

[…] [2] It’s worth noting here that there is obvious overlap between the potential latent in infrastructure which we are describing, and the tussle to describe an appropriate alternative to modernist planning which we have recently discussed. We described this infrastructural potential with a more explicit focus on that overlap in our Bracket 1 essay, Hydrating Luanda: […]

[…] […]

[…] processes, was itself farmed?” And, as a response, they are proposing four basic forms for fog farming in Luanda, including a highly formal farming architecture for the central districts of the city […]

[…] of course, we’ll draw up the new mega-infrastructures of the 21st century — user-owned fog-farming networks and hovering re-purposed military drones broadcasting pirate wi-fi over financial districts and […]

[…] Photo Kostadin Luchansky Some of the essays particularly stand out. Stephen Becker and Rob Holmes wrote a fascinating text about how a technique called Fog Farming could solve the water supply issue in […]