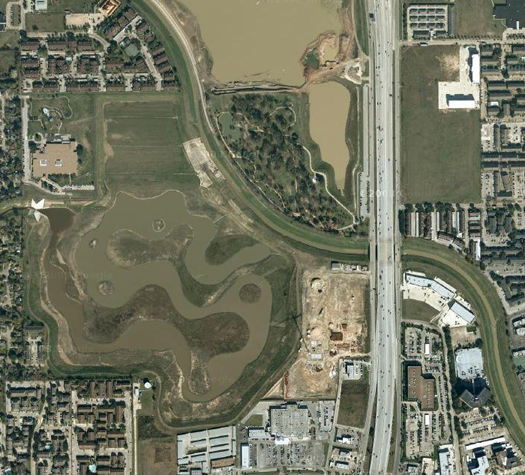

As long as I’m on the subject of urban parks that serve as components of flood management systems, I ought to mention the recent Buffalo Bayou Promenade in Houston, which is not only an admirable and forward-thinking project from a city not known for its innovative ecological design (though they have built a rather seductive tangle of on and off ramps), but also manages to mash three of my favorite things — urban parks, flood control and freeway interchanges — into the same space:

Water on Buffalo Bayou can rise rapidly from sea level to 35 feet (11 m) deep, often within several hours. SWA met that challenge by designing all landscape plantings, trail markers, signage, benches, lights to withstand periodic submersion by muddy, debris filled flood waters. In the event of high water, small hydrants, spaced conveniently, wash off any deposited silt, returning it to the bayou before it dries.

Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1857 description of the bayou landscape emphasizes the expansive reach of the floodwaters that the Promenade accomodates, as well as the close tie between hydrology and economy which gave birth to Houston:

“The Brazos bottoms near by, are four or five miles wide. They are of very great fertility, and the land commands high prices… The bottom is seldom reached by freshets, but was covered in those of the years 1833, 1843, and 1852. We were landed from the ferry near night, and, barely accomplishing the dark and heavy miles of bottom by twilight, camped under a group of huge oaks, at the edge of the great coast-prairie.

To Houston the road lay across a flat surface, having a wet, sandy or “craw-fish” soil, bearing a coarse, rushy grass, diversified by occasional belts of pine and black-jack. We had reached the level prairie region of the coast, and in fact saw henceforth not one appreciable elevation until we crossed the Mississippi. Five miles from Houston we entered a pine forest, which extends to the town.

Houston, at the head of the navigation of Buffalo Bayou, has had for many years the advantage of being the point of transhipment of a great part of the merchandise that enters or leaves the State. It shows many agreeable signs of the wealth accumulated, in homelike, retired residences, its large and good hotel, its well-supplied shops, and its shaded streets. The principal thoroughfare, opening from the steamboat landing, is the busiest we saw in Texas. Near the bayou are extensive cottonsheds, and huge exposed piles of bales. The bayou itself is hardly larger than an ordinary canal, and steamboats would be unable to turn, were it not for a deep creek opposite the levee, up which they can push their stems. There are several neat churches, a theatre (within the walls of a steam saw-mill) and a most remarkable number of showy bar-rooms and gambling saloons…

Houston (pronounced Hewston) has the reputation of being an unhealthy residence. The country around it is low and flat, and generally covered by pines. It is settled by small farmers, many of whom are Germans, owning a few cattle, and drawing a meagre subsistence from the thin soil… In the bayou bottoms near by, we noticed many magnolias, now in full glory of bloom, perfuming delicately the whole atmosphere. We sketched one which stood one hundred and ten feet high, in perfect symmetry of development, superbly dark and lustrous in foliage, and studded from top to lowest branch with hundreds of great delicious white flowers.”

Another 19th century traveler, Edward King, praised the natural beauty of the bayous:

“The bayou which leads from Houston to Galveston, and is one of the main commercial highways between the two cities, is overhung by lofty and graceful magnolias; and in the season of their blossoming, one may sail for miles along the channel, with the heavy, passionate fragrance of the queen flower drifting about him.

Houston is set down upon prairie land; but there are some notable nooks and bluffs along the bayou, whose channel barely admits the passage of the great white steamer which plies to and from the coast. This bayou Houston hopes one day to widen and dredge all the way to Galveston; but its prettiness and romance will then be gone.”

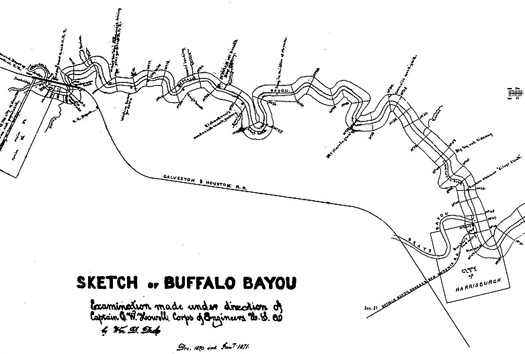

Though the Buffalo Bayou is one of the few riparian systems in Harris County to retain something of the character Olmsted and King described, the Buffalo Bayou today is a highly designed hydraulic system. Damaging floods in the 1930’s (documented in a government report entitled “Wild River”) prompted the construction of reservoirs, straigthened and deepened channels, and the replacement of streambank vegetation with concrete streambanks throughout Harris County.

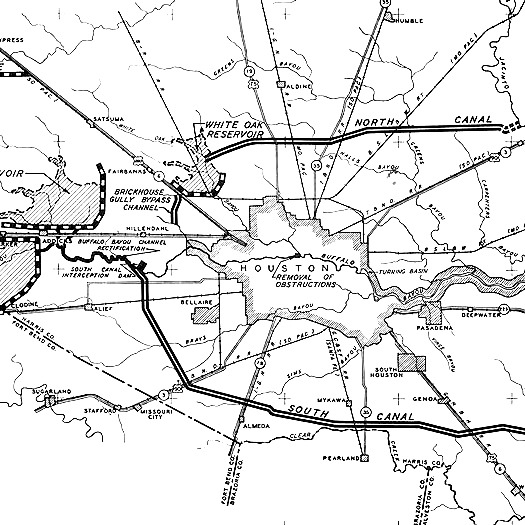

In the 1940, the Army Corps of Engineers released a plan to divert the flows of White Oak and Buffalo Bayous around Houston through the construction of a massive system of canals and reservoirs. While the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs were built (and along with the dams that sustain them, still regulate the flow of water passing down Buffalo Bayou), World War II interrupted the planned canal construction. By the time the war passed, Houston had grown so rapidly that the original canal routes were obsolete and inadequate. “Wild River” was updated by the Harris County Flood Control District and re-issued in 1951. An updated flood reduction plan was ready by 1954, but opposition to the Army Corps of Engineers’ methodology mounted, culminating in the formation of a civic association named the Bayou Preservation Association, and brought a final halt to thirty-five years of attempts to beat back the floods with ever-increasing channelization, damming, and re-routing.

The Buffalo Bayou Promenade fits into the more recent program of the HCFCD, which has included projects such as the Greens Bayou Wetlands Mitigation Bank (a 1,400-acre constructed wetland — though, if I recall correctly, there is some debate about the worth of mitigation banking) and the Arthur Storey Park Stormwater Detention Basin, which, like the Buffalo Bayou Promenade, serves both as park and flood control system.

While I’ll admit to seeing a bit of rough charm in the ‘before’ images of Buffalo Bayou, I am quite pleased to see the ASLA honoring this sort of exceptionally useful project, as I suspect the ability to accommodate divergent layers of program — river, park, highway — will be essential if landscape architects are to retain any significant influence on the evolution of American cities, given the powerful apparatus of NIMBYism which resists (quite rightly) Olmstedian intervention and the static weight of a couple hundred years of city-building.

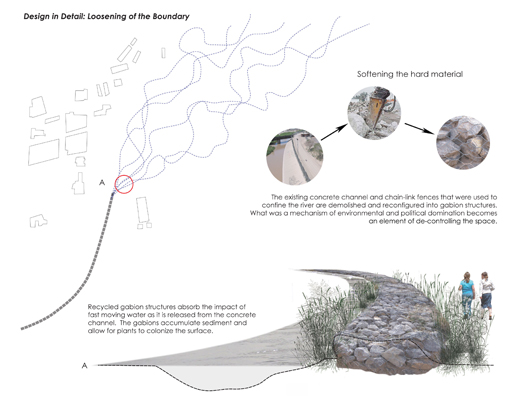

Another project which is situated in a similarly unstable riverine site is Brett Milligan’s Inundating the Border, winner of an ASLA student award a couple years ago. Inundating the Border is concerned with a section of the Rio Grande between Ciudad Juarez, Mexico and El Paso, Texas, whose concrete channelization and dual service as river and border permits Milligan to explore fertile terrain in both ecology and politics:

In a 1962 agreement between the United States and Mexico, the river border between Juarez and El Paso was moved and stabilized within a concrete channel. This change left a void in the urban fabric between Juarez and El Paso that still exists today. [Inundating the Border] utilizes the urban void created by historical shifts of the border between Juarez and El Paso as an opportunity to redesign the border as a fluctuating, indeterminate space. This process begins by releasing the Rio Grande (the border by treaty definition) from the concrete channel, thus allowing flows of the river to meander through the floodplain, constantly changing the precise location and thickness of the border. Through time (daily, seasonal, and mechanistic) the river shifts, migrates, floods and runs dry, and these processes create entire spaces of migration in which all elements—the ground plane, ecologies, and human occupation are transitional and constantly changing.

While the Bayou Promenade allows for a great deal more accomodation of indeterminacy than traditional flood control engineering, Milligan’s proposal pushes that accomodation even further –not just accepting that portions of the area around a river in a flood plain will flood occasionally, but removing a large section of the concrete channel of the Rio Grande, making a few strategic insertions to help mold the transition between concrete and earthwork river banks, and setting aside a large tract of land to watch the river re-shape itself. It might be more properly thought of as a landscape experiment than a landscape plan.

[…] of stormwater infrastructure and public parks being previously praised by mammoth in both Texas and the Netherlands. Waterpleinen is featured in the latest issue of Alphabet City, Water. Read […]

[…] Brett Milligan, whose project “Inundating the Border” mammoth briefly touched on in an earlier post on Texas hydrology, is writing an excellent blog entitled Free Association […]