I’d like to echo Rob’s delight at being able to attend the final critique of the Landscapes of Quarantine Studio in NYC hosted by BLDGBLOG and Edible Geography. We’ll make sure and keep folks posted on the details of the studio’s exhibit at the Storefront for Art and Architecture, which is due to open in early March. I can’t wait to see what the participants develop.

Coming away from Saturday’s discussion, I couldn’t shake my fascination at the potential quarantine has to shape novel economies within existing systems – a line of thinking drawn from Front Studio’s project. They investigate the spatial and social implications of having a quarantined city-within-a-city. Proposed are a variety of tactics for segregating populations in an integrated environment, including appropriating under-utilized city and building infrastructure (such as fire escapes and phone booths) for a quarantined population’s circulation and disinfection; and color-coding portions of building facades (and scenting the infected population) as stay-away signifiers for the healthy population.

As is brilliantly communicated to the citizens of New York in Amanda Spielman’s project, NYCQ, disease spreads on virtually everything. Because goods are equally (along with people, and, apparently, pets) disease vectors, the simultaneous integration and bifurcation of contaminated / non-contaminated populations proposed by Front Studio challenges us to consider the exchange of goods between them. The system must enable the quarantine of people, as well as goods – inevitably establishing an economy of quarantine.

When good becomes vector, it still has value. But a fixed overall supply of goods combined with a leftward-shift in the demand curve (from an entire population to a contaminated population) must result in a lowered price for that good.

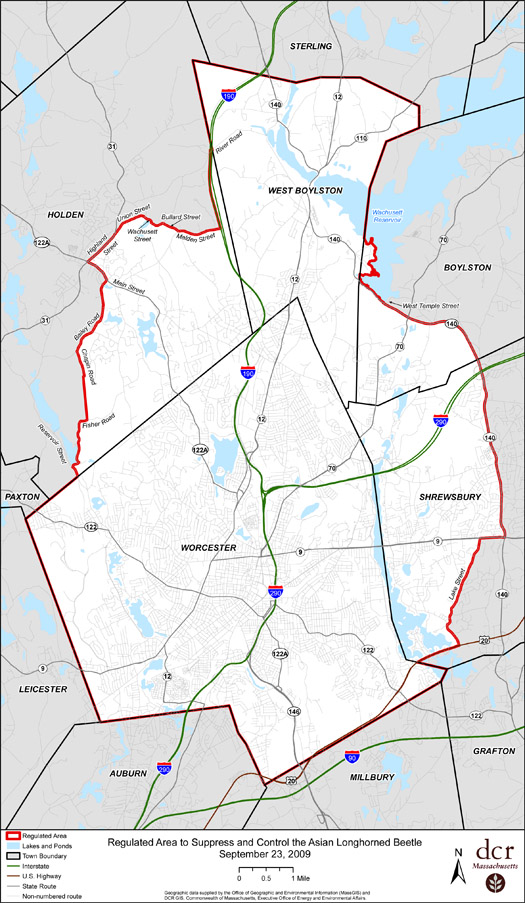

An instance of this exact phenomena is currently underway in New England. The Asian Longhorned Beatle is causing the quarantine of trees in certain locations throughout Massachusetts and surrounding states. Now, quarantining trees might not seem to be such a big deal, considering that trees don’t move – but, regulations on the transportation of trees into and out of the area are having a significant impact on the resale value of firewood. The areas under quarantine have an over-saturation of wood, and nowhere to send it. The fact that non-quarantined wood from nearby areas needs a permit (an arduous process) to be transported through or near quarantined areas only serves to further exacerbate the issue.

What is so fascinating about this is that is incentivizes breaking into quarantine. A family living in suburban Natick with a camper shell on their pickup truck can’t resist the dirt-cheap firewood in Worcester because of the extra-cold New England winter. A poor family living in the Bronx decides to buy their cereal for 75% off (after it had been scanned, flagged, and sent for resale in a quarantine-only store during an outbreak of mutated H1N1 in NYC) because they can’t afford the now premium-priced, ‘guaranteed H1N1 free’ supply; so they sneak into a quarantine store, or perhaps buy it from illicit Q-market goods smugglers. To make matters worse, the incentive would be greatest at the beginning of an outbreak, during the most critical moments for containment, because that is also when the disparity between markets is greatest (resulting in the largest possible leftward shift in the demand curve, and consequent drop in price of the good. Another way to think about this is realizing that if everyone was quarantined, the price differential would disappear.)

Does incentivizing entry into quarantine encourage or restrict the spread of disease? If the success of a quarantine has less to do with its comprehensiveness than its imporosity, incentivizing entry would likely pose a big problem. If nothing else, a comprehensive quarantine response which included goods would probably over-emphasize the affect of an outbreak on the poor. And I think it’s important to note that incentivisation could happen organically, not as result of any program.

Because the moment of incentive occurs when a good is flagged as quarantined, our choice is either 1) don’t mark goods, and have no quarantine or 2) mark goods, and incentivize entry into quarantine. Which is worse? Too much quarantine, or not enough?

[…] Quarantine Economies – mammoth // building nothing out of something m.ammoth.us/blog/2009/12/quarantine-economies – view page – cached I’d like to echo Rob’s delight at being able to attend the final critique of the Landscapes of Quarantine Studio in NYC by BLDGBLOG and Edible Geography. […]

interesting! … but wouldn’t difficulty of breaking into quarantine then raise the prices of quarantined goods again? if you have to bribe somebody to get in, or buy expensive equipment to break in, then aren’t you losing the savings of buying cheaper, quarantined food?

I think it definitely would – the question is how much, and whether that makes up the price difference. Which is determined by how secure the quarantined goods are, and how great the incentives are, and a hundred other things I’m probably not even thinking about. The more fundamental issue – that there can exist strong incentives to break into quarantine – remains a problem if trying to contain the spread of a disease.

There are a lot of other probable implications I didn’t really discuss, quarantine black markets aside. If you have to hold a good for a few weeks, or pay to disinfect it, then that raises its cost. If you have to destroy it, that raises the cost of the remaining goods. How dramatic might these price fluctuations be? What kind of social effects would they have? I would be really interested in reading papers on this topic by people who know economics much better than me.

[…] quarantine economies – mammoth // building nothing out of something"A poor family living in the Bronx decides to buy their cereal for 75% off (after it had been scanned, flagged, and sent for resale in a quarantine-only store during an outbreak of mutated H1N1 in NYC) because they can?t afford the now premium-priced, ?guaranteed H1N1 free? supply; so they sneak into a quarantine store, or perhaps buy it from illicit Q-market goods smugglers. To make matters worse, the incentive would be greatest at the beginning of an outbreak, during the most critical moments for containment, because that is also when the disparity between markets is greatest…"(tags:pol speculative ) […]

foreseeing sellers of counterfeit uncontaminated goods developing a market among the poor…

The Longhorned Beetle quarantine has echoes of the British Foot & Mouth outbreak five years ago: an incompetent, indiscriminate (and often brutal, to livestock) Government department strangled the entire rural economy with movement controls on everyone and everything.

The quarantine and economic lockdown may or may not have been effective in protecting this one, narrow, privileged economic interest. It permanently damaged the wider economy.

So… Would local Law Enforcement turn a blind eye to violations of a quarantine imposed for reasons unrelated to human health?

Think that one over. And, once you’ve had two or three or four of those, possibly with an unrelated anti-terrorism curfew and some roadblocks by the TSA, the states affected by it will have a healthy black economy of smugglers… Which may well circumvent a flu quarantine.