While researching a forthcoming post last night (which I can assure you will live up to the site’s title, at least in length), I stumbled across this fantastic interview with Alan Berger conducted by Abitare. The interview deals first with Berger’s work in the Pontine Marshes, but expands to discuss his general working methodology (airplane reconnaissance), other projects, academic philosophy, and general thoughts on the future of landscape architecture as a discipline.

I’m particularly interested by two things in the interview. First, Berger’s Pontine Marshes project indicates the potential of design disciplines to contribute something — in this case, a designed ecology — to the organization of landscape infrastructures which those who have typically organized them (politicians, scientists, engineers) do not. This seems to me to be a question which is often left unanswered when landscape/architects make proposals for infrastructures: it’s clear what we get out of our involvement in the work (we get to do exciting projects and have the kind of influence the profession craves), but it is often much less clear what about our contribution to the project ought to convince a government (at these scales, one is almost always working with government) to hire a designer rather than an engineer as the project coordinator (shorter version of this question: why would you hire a landscape architect to design a sewer?). That Berger has been able to convince the provincial government to pursue the implementation of the project indicates that they’ve found real value in his approach to the remediation of the Marshes.

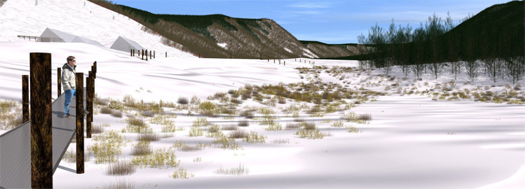

Second, I’m quite intrigued by the historical trajectory of Berger’s work, by how the cultivation of relationships with scientists (the EPA, in the case of the Breckenridge mine project) and politicians (the provinicial government, in the case of the Pontine Marshes) has allowed Berger to make a direct and linear transition between unfunded research projects and the funded implementation of landscape infrastructures. While it’s quite possible that this trajectory is only possible within an academic environment which provides the flexibility needed to pursue years of unfunded research and thus that this is not a plausible trajectory for more traditionally organized architectural firms, it nonetheless illustrates a clear path for developing the agency of designers in new fields.

Berger:

“I call myself a landscape architect with the understanding that somehow the design world and the culture outside of the design world will catch up with me.”

seriously? Those landscape architects who see themselves as fighting against the complacent grain of their field are a dime a dozen. You have academics and practitioners in every field, its not a new invention. . .

With that off my chest, I must say I enjoyed the interview and I like Alan’s work very much–thanks for pointing out the link guys.

Well, efforts to rename the profession because of perceived inadequacies within the profession, efforts which are by no means limited to Berger, don’t seem particularly useful to me, as they’re primarily cosmetic and somewhat self-serving (the goal being to differentiate between those landscape architects and us [insert preferred alternate term here]).

Yes — as I hinted in the last sentence of the post — I do think it’s a bit harsh to slam practitioners for continually treading the same ground when many are barely staying afloat (or aren’t at all), and so have every incentive to be as conservative as possible (and lack the financial freedom that Berger’s role in academia affords him). And “…will catch up with me” does come off as unfortunately self-aggrandizing, but it’s presumably an extemperaneous interview, so I’d tend to not to read too carefully between the lines of his word-choice.

But despite all that, I think Berger really is onto something (as I’m guessing you agree, given that you say you like his work), in that he is pushing the profession into genuinely new territory and that its an important territory which the profession as a whole has generally ignored (whether for lack of interest or for lack of models for developing agency in that territory). So I think it’s to be expected that, if he believes that work is of great importance, he’d be a bit frustrated with a profession that generally shows little interest in it.

I assumed that it was relatively commonplace and an accepted alternative business model to work on speculative/experimental projects as a consultant with the safety net of an academic post underneath. In fact, I think there are several good ones who use their investigations to create academic courses, and then use the work generated in those courses to push their investigations further.

I think of people like Kristina Hill, Belanger, Walter Hood, Mason White, and Elizabeth Mossop, or Randy Hester and John Lyle back in the 80’s. Perhaps Berger’s focus on scientists and bureaucrats is unique?

It is definitely a great model, a way of doing significant work with an academic post. I wonder to what degree it affects their teaching?

faslanyc:

Yes, it definitely is (all the examples you noted, and many more), but what I think is much less common is parlaying that speculative work into the opportunity to design landscape infrastructures, through connections developed with those scientists and bureaucrats.

My take on Berger is that sometimes the rhetoric and the ego slightly mars, or obscures the quality of his own research (as Elizabeth Meyer’s comment at the end of interview eloquently points out). But that aside,unquestionably his research is affecting the trajectory and scope of landscape and environmental design, in a very positive way.

Berger effectively makes this point about the role of research clear in Drosscape–saying its about time that landscape architects and related designers create, rather than follow received design agendas via the quality of their research. In another interview in Kerb 2 years back he expressed his distaste of design competitions for that very reason.

Whereas Corner ‘expanded the field’ of inquiry and design agenda in the 90s through his writings, he now chases the same work as everyone else.

I think Berger has picked up where Corner left off and continues to lead the way to broader and more relevant questions. This type of research is both the privilege of an academic position as well as its responsibility.

“This type of research is both the privilege of an academic position as well as its responsibility” — well said; maybe I’m overemphasizing the degree to which Berger’s doing more than many others do to use that research as a direct angle into practice, instead of letting it remain “merely” research (which can also be a valid methodology), but I’m having a hard time thinking of too many other examples of academic research developing into the design of landscape infrastructures.

I’d sort of come at the question from the opposite direction, so maybe that’s part of why I was excited when I started to think about the Pontine project — I wasn’t looking for academics whose research had developed into design, but looking for examples of landscape architects designing large-scale landscape infrastructures (and in particular, infrastructures associated with continuing or revitalized industrialization). It seemed to me that there are a lot of barriers to landscape architects negotiating roles in the design of such infrastructures, including the question mentioned in the post (what do landscape architects offer that, say, engineers don’t?, and then convincing the power structure that you’ve got a good answer to the question — which Berger has been able to do), as well as the difficulty for ordinary landscape firms of cultivating the contacts and relationships necessary to be taken seriously in such matters.

Maybe the end statement though — “it nonetheless illustrates a clear path for developing the agency of designers in new fields” — was completely obvious, but I’d think that if it were really so obvious (or easy) it’d be more common.

i’d agree.

if you expanded infrastructure to include social spaces (social infrastructure?) you would have to include the berkeley guys walt hood and randy hester as people approximating this model.

but yes, the majority of academics are not doing much beyond pure academia and a little side work.

you guys seem to follow belanger a bit- i was under the impression his toronto “center for landscape research” was explicitly taking this tack- work with scientists and bureaurcrats to develop proposals for executing real infrastructure work. Don’t know that he’s had time for a successful example yet, though. Am I correct there?

Yeah, that’s exactly the impression I’ve gotten — I haven’t talked to (or met) Belanger (or talked to any of the other Toronto folks, a couple of whom I have met) about it, but my impression is that there is some work germinating, but it is moving very slowly, as work at such scale and involving so many layers of bureaucracy is likely to. His words from “Landscape as Infrastructure” (PDF):

“In stark contrast to the 20th century paradigm of speed, the effects of future transformation will be slow and subtle, requiring the active and sustained engagement of long-term, opportunistic partnerships that bridge the private and public sectors.”

[…] Getting a lot bigger, Mammoth covers mammothly (as they promised) the best architecture of the decade. Unlike so many lists of flashy blingitechture and navelgazing […]

[…] « alan berger interviewed high-speed rail funding » […]

[…] As fascinating and long as the belt is, though, it is a relatively minor infrastructure in comparison to the vast — eighteen miles long — Salt Ponds it feeds its cargo onto the shores of. And those Ponds perhaps present an opportunity for a much more substantial landscape intervention, one which would not merely seek to ameliorate the conditions produced by accepted industrial processes (as Aronson’s conveyor belt does so skillfully), but would look to fundamentally reorganize those processes. This difference of opportunity may serve to effectively highlight the difference between two possible answers to the question FASLANYC poses, “what value do landscape/architects add to the design of infrastructures?”, a question which mammoth has previously been concerned with. […]

[…] via @bldgblog; the Pontine Systemic Design previously on mammoth here and here. Read the full article at MITnews, which also contains a gallery of images.] This […]

[…] to be our gift to infrastructure, what will? The obvious response (which mammoth and others have discussed elsewhere) is that if architects want to be more than infrastructural decorators, we’ll need […]