Our intention for a while now has been to write a bit more about what we like to refer to as “landscapes in search of an architect”, or those places whose phenomenological, industrial, psychological, geological, and/or ecological (and that list could go on, and on) characteristics suggest to us the possibility of an exceptionally interesting architectural intervention. These posts are not a description of that intervention, but rather a running catalog of such places, fertilizing our imaginations.

Approximately four hundred million years ago, Detroit — situated then as now on the massive Laurentian craton, though at that point in geologic history, known as the Devonian period, Laurentia was part of the Euramerican supercontinent — lay within what is known as the Michigan basin, a shallow, arid expanse of land which was periodically filled by salt-laden ocean water as it sunk towards the center of the earth. These temporary saline lakes rapidly evaporated, leaving behind miles of salt beds, which now lie beneath four hundred million years of shale, limestone and sandstone.

One of the most remarkable things about geology, though, is that geologic forces convert time into distance, and so those salt beds lie a mere quarter-mile beneath the city’s surface. Around the beginning of the 19th century, the presence of these salt beds was discovered and miners — who are, in some very real sense, time travelers — began to translate four hundred million years into eleven hundred thirty-five feet of mineshaft.

But time travel is neither easy nor cheap, and the Detroit Salt and Manufacturing Company which began those excavations soon gave way to the Detroit Salt Company, which was acquired by the Watkins Salt Company and reorganized as the Detroit Rock Salt Company, before being bought by the International Salt Company. The Detroit salt mine has operated almost continuously since then, providing salt for industries — primarily food and leather in the early twentieth century — and winter road maintenance, the primary use of Detroit’s salt today.

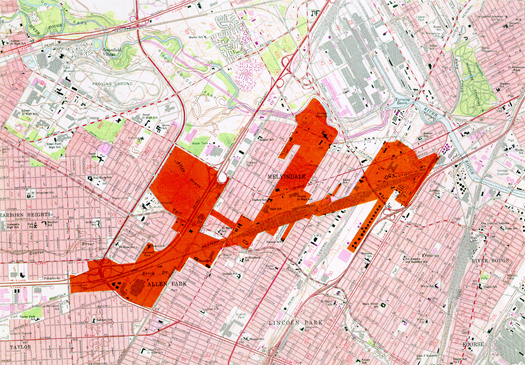

Today, the salt mine spreads from it’s entrance at 12841 Sanders Street over fifteen hundred acres of Detroit, adjacent to Henry Ford’s famous River Rouge plant, and spider-webbed by over a hundred miles of subterranean roadway. The Detroit Salt Company’s website describes the contemporary layout and extraction processes:

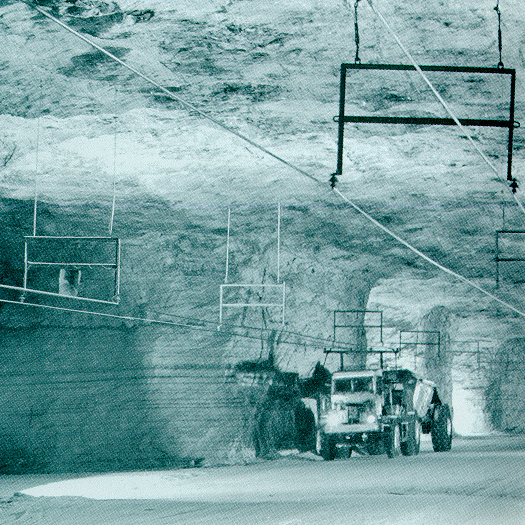

Approximately 1,000 feet of rock lie atop the vein of salt. To safely extract the salt from the deep deposits, Detroit Salt employs the “room and pillar” system. This method creates massive pillars, which support the mine roof and the overburden separating the mine from the surface. Parallel galleries – or rooms – give the mine a checkerboard pattern, allowing machinery to easily move a design for future expansion and serves as an air course for fresh, ventilated air in worker-occupied areas.

The extraction process begins with undercutting the mine walls level with the floor. A self-propelled undercutter carves channels at the base of the deposit and across the entire room. This channel fosters efficient explosive blasting and creates a smooth mine floor. A special drilling machine then bores 40 or more holes into the salt face, which miners then prime and with pellets of explosive materials. Blasting-cap wires are spliced together, placed in the open ends of the hole and then attached to an electrical ignition cap. Miners ignite the explosives, creating a blast that dislodges 800 to 900 tons of rock salt in less than three seconds. The depth of the mine and cushion of the overburden absorbs the blast vibrations, preventing any surface damage to immediate and surrounding areas.

After the blasting, miners scale loose pieces of rock salt from the roof and side walls. Huge front-end loaders remove and transport the blasted rock salt to the primary crusher. Loaders dump 12-tons loads of salt into powerful spinning crusher, where large pieces are quickly devoured, emerging no lager then eight inches in diameter. The salt leaves the primary crusher via thousands of feet continuous conveyor belt. It is refined and crushed once again before being transported to the hoisting shaft where skip hoists bring 10-ton loads to the surface in a matter of seconds. Upon reaching the surface, the salt is sent to either a rail car for shipping or stacking conveyor to store for later use…

The exceptionally odd aggregate form of the mine — extending only westward from the mine shaft, and only beneath large agglomerations of property, avoiding small property owners — results from the inefficiency of the legal processes for securing the mineral rights for those properties, which produces a minimum acreage beneath which acquiring the mineral rights wipes out the relatively slim profit margin involved in such difficult sub-surface mining. The mine, then, is molded not just to the geology of the city, but to its legal morphology, property lines literally written in stone.

Which reminds me of the recommendation, seen at Super Colossal, made by a committee involved in the planning of the new urban area in Singapore, that there should be an “underground master plan”, involving the development of “subterranean land rights, a valuation framework, and… a national geology office”. Perhaps it’s time to open an Office of Subterranean & Geological Urban Planning in Detroit, in anticipation of a Cappadocian future — whatever the psychological implications of living below ground might be (and there’s certainly a valid argument to be made that they wouldn’t be entirely positive), it is astonishing to think that the cities of the future could lie beneath our sidewalks, factories, and abandoned lots.

The title of this post is quoted from the Detroit Salt Company’s webpage; John Nystuen’s 1999 article, Metropolitan Mining: Institutional and Scale Effects on the Salt Mines of Detroit, is a fascinating (if slightly academic) study of how economic and legal constraints interact with geology and mine operations to produce a subterranean landscape, and the source for all the images of the Detroit salt mine in this post; if I were allocating grant funds, I’d be sure to get thenorthroom to survey the Detroit salt mine as they did the tunnels of Guanajuato (link via F.A.D.); finally, Atlas Obscura has an entry on the Detroit salt mine, which includes a handful of images of the 12841 Sanders Street site.

[…] in search of an architect” mentioned at m.ammoth.us and we take these words from their post the city beneath the city: One of the most remarkable things about geology, though, is that geologic forces convert time into […]

[…] where all that road salt comes from? A question that’s quite topical today. Mammoth has a post up on an operating salt mine beneath the city of Detroit. Detroit Salt […]

[…] would be potentially useful, and are often located in surprising places. There is, for example, a giant salt mine located over 1000 feet under Detroit, Michigan. This mine includes over 100 miles of roads, and excavated portions are used to business and […]

[…] the city beneath the city – mammoth // building nothing out of … Feb 2, 2010 … The Detroit salt mine has operated almost continuously since then, providing salt for industries … […]