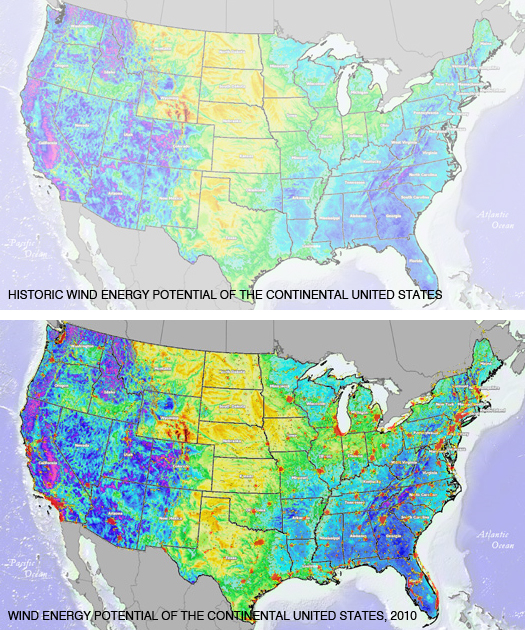

[Comparative historic and contemporary heat maps of the wind energy potential of the continental United States, via NASCA.gov; NASCA documents indicate sources for their imagery include AWS Truewind/NREL via Wired Science and NOAA/NASA]

The North American Storm Control Authority (NASCA), like its predecessor, the North American Water and Power Alliance (NAWAPA), which rebuilt the Rocky Mountains as a massive hydrological reserve and power source, enabling the NAWAPA Three (the United States, Mexico, and Canada) to break OPEC’s stranglehold on world energy supplies in the mid-seventies, serves the electricity-generation needs of an entire continent. Unlike NAWAPA, though, NASCA (which is pronounced “näs’kä”, like the lines in the Andean desert) supervises a distributed and resilient infrastructure, embedded into the fabric of the cities it serves.

On August 29, 2005, the sudden collapse of a section of the Rocky Mountain Trench sent massive flood waves hundreds of feet tall racing down the Frasier River and tragically washed much of Vancouver out to sea, forming in the process a chiseled scar known as the “North Channeled Scabland”. This decade-defining infra-natural disaster plunged much of the West Coast of both Canada and the United States into an extended blackout as the waters which fed the great chains of dam turbines dried up. Shocked into action, North American lawmakers realized that they could not depend on a vast and singular — but fracture-critical — infrastructure to power the continent.

Through much consultation with urbanists, meterologists, climatologists and architectural historians, the combined governments of North America settled upon the scheme which NASCA now regulates: passive architectural climate modification devices, modeled after vernacular construction techniques which produce wind-flows by exploiting temperature and pressure differentials, but also containing within themselves wind turbines and windmills of all sizes, have been deployed throughout the cities of North America, attaching to rooftops, windows, former grain silos, abandoned warehouses, fifteenth-floor penthouses, and suburban shopping malls. Meanwhile and below-ground, sewers and streams long-dormant beneath pavements have been threaded into a network of modernized, urban qanats. Individually, the effect of these devices is minor; an air conditioning system rendered unnecessary here, a warehouse cooled there. Collectively, though, these augments produce enough micro-climatic alterations to alter the productive windscape of the entire continent, channeling and concentrating sufficient wind flow to make cities the geographic center of North American power generation. Every house a turbine, every office park a wind-farm.

[A distributed infrastructure is but one way in which an infrastructure might be designed for failure.]

I didn’t quite line Florida up right in the second map, I’m afraid. Use your imaginations.

Design fiction?

I am not sure why i left the ? there. Of course it is..

Pics or it didn’t happen.

Oh, I’ve got the pics (Nam: or is it?), but NASCA won’t let me show them.

Reminds me of Alexis’ post about air conditioning destroying local architecture practices, because you could just throw BTUs at the cooling problem.

Seems to me that the solutions that the NASCA ended up proposing were interesting for how highly contextual they had to be.

Tim: indeed — though, ironically, the ubiquity of air conditioning is exactly what NASCA has sought to emulate. A storm controller on every chimney, as they say.

It’s a shame that we’re seeing the same trend — the destruction of local architectural practices — in the Himalayas, as nuclear-powered ice sheets replace traditional glacier farming. Do we need a Slow Glacier movement?

Slipping between parallel universes, and speaking of Alexis, he tweets this afternoon with regards to Bloom boxes, referencing that very same post:

Perhaps Bloom and NASCA should converse? I love the idea that the way to impact vernacular architecture is not to engage in academic glamorization (a la Learning from Las Vegas), but to do the absurd: make storm control a vital part of housing technology, or build a small black box which can slash houses’ energy import needs and carbon emissions, or redesign buildings as stillsuits and aquifers.

Spinning off of Tim’s post, wouldn’t a map that showed the effectiveness of windcatchers be useful? I suppose you’d overlay this wind intensity map over humidity and temperature factors. I think one would discover all sorts of interesting geographical information by overlaying the various climatic factors related to regional design.

Windcatchers are fascinating in that they are so elemental, playing the hot desert winds against cool water to effectively humidify and cool the human environment. That is air conditioning.

цarьchitect: Also indeed. Perhaps some developer with an unusual degree of foresight could forecast the future re-integration of climatic architectural variations into mass housing construction, and would be interested in those maps? I know I am.

Seems like a job for the Internet of Things.

Don’t look at me, I’m on my lunch break.

[…] inspired by: Star Archive, Storm Archive, Storm Control Authority, Meteorological Alchemy, Carcinogenic Storms, Life on […]