Magazine on Urbanism‘s twelfth issue, Real Urbanism, was released last Thursday; mammoth is quite pleased to have had the opportunity to contribute to this consistently provocative publication. For this issue, MONU called for entries which “explore how people in the real estates business perceive and conceive cities”:

“What do cities look like in the eyes of real estate investors, property managers, and urban developers? What is a good and what is bad city according to real estate agents? [Real Urbanism aims] to illuminate the hidden forces that ultimately establish the physical reality of cities.

But this issue is not meant to be merely polemical and critical of financial forces and economic power that are related to real estate in cities – no Don-Quixotean anti-capitalistic battles shall be fought – but rather attempts [are] made to reveal the particular interests of people involved in the real estate sector and their consequences on the built environment. What concerns [MONU] most is to put those topics on the agenda and to understand their impacts and dependencies.”

The resultant collection of research interrogates the effect these forces and interests have on the shaping of our cities. Some of the topics discussed include the role of the Solidere development corporation in reshaping post-civil war Beirut’s central business district, the possibility that architects should become developers (a suggestion which is almost always received positively here at mammoth), and the negative consequences of exclusively profit-oriented development in both Shanghai and Central Europe. In addition to many more articles, the issue also includes interviews with Bjarke Ingels and Magriet Smit (a Rotterdam-based developer).

Mammoth‘s contribution to the issue, “The Shelter Category”, is reproduced below. In it, we suggest that the primary function of the home in America is, ironically, not shelter but wealth creation, and use the Home and Garden Television Network as a vehicle to investigate and critique this culture of ‘equity urbanism’.

You can order a copy of Real Urbanism here, and you can watch a preview of the issue here.

A Machine for Making Money Le Corbusier was wrong: the home is not a machine for living. It is a machine for making money. Though romanticized as an American emblem of personal responsibility, security, and stability, the true impact of home ownership is derived from its utilization for the cultivation of personal wealth (1). American homeowners understand this. Architects, by and large, do not.

2 Net Revenue and viewership figures cited here are from Scripps Networks Interactive, Inc quarterly SEC filing form 10-Q (submitted 11-06-09).

Straining for continued relevance and agency within today’s multi-billion dollar construction industry, designers and theorists expend significant effort attempting to understand tactics and politics used by the agents of real urbanism, including developers, real estate agents, and financiers. But what good is this understanding if we do not comprehend the ownership culture at the foundation of that industry?

The Shelter Category Media Home and Garden Television (HGTV) is a lifestyle media brand that unapologetically caters to American home ownership culture. We can learn from HGTV in two ways: by studying the consumer demand to which HGTV responds and by studying the demand which their programming fosters. With content focused exclusively on the ‘shelter category’ — the industry-insider’s term for expertly presented opinions on residential real estate, decorating, and lifestyle options — HGTV produces and broadcasts over 7,000 hours of television into 99 million U.S. and Canadian households annually. The success of parent corporation Scripps Networks Interactive quickly dispels any remaining doubt about their capacity to assess and shape consumer demand: this publicly traded media company generated $268,851,000 during the first three quarters of 2009. (2)

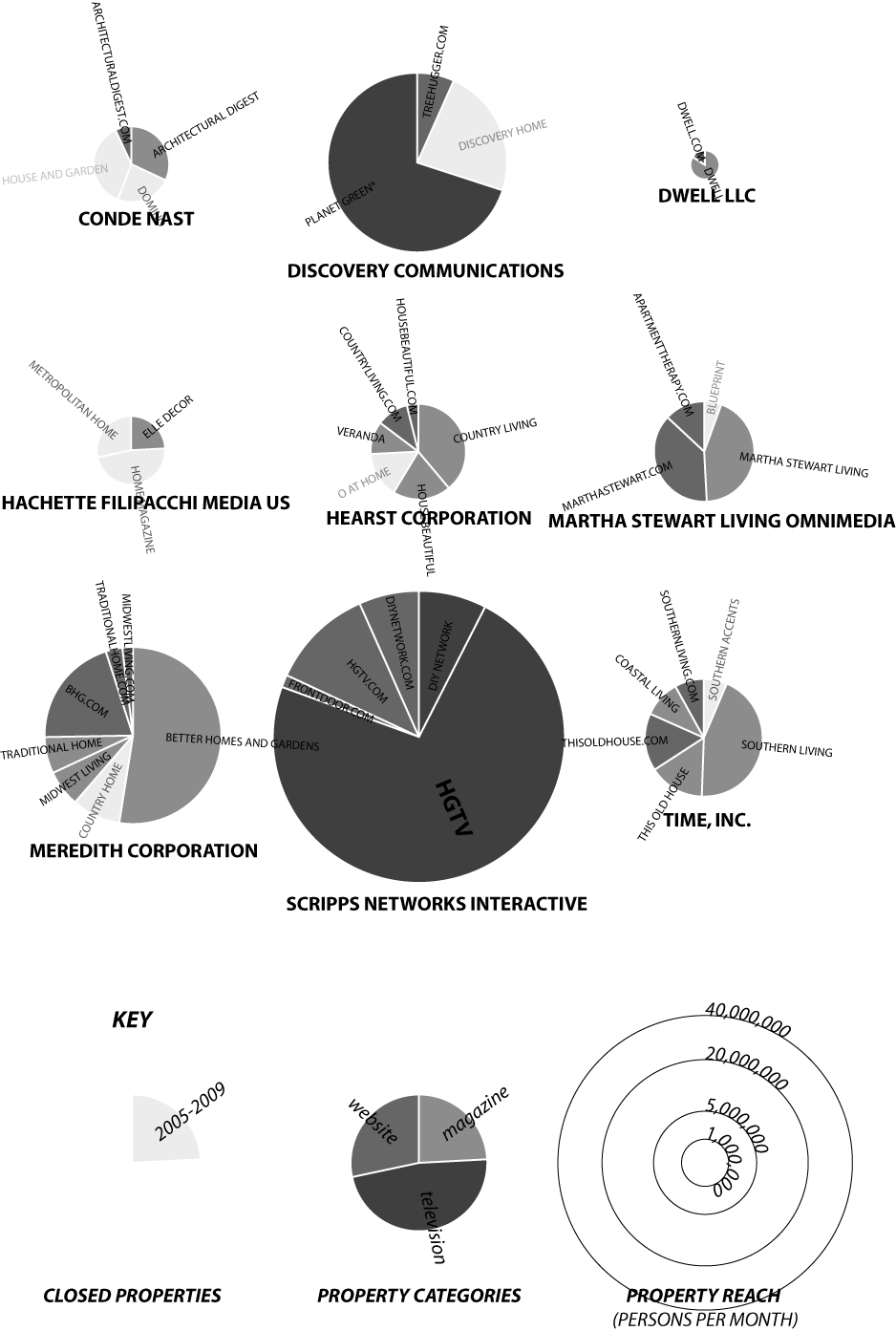

[Figure 1: shelter category media – represented here by graphs of the populations reached through magazines, websites, and television channels by nine of the largest corporations which own shelter category media – represent an incredibly large and influential catalog of ideas about the built environment, yet are rarely studied by architects.]

The success of HGTV and other populist shelter category media, ranging from the pop eco-modernist Dwell to the staid and formal Architectural Digest, reflects both the existing market demand and cultural values to which they respond as well their ability to create additional demand and shape those values. Figure 1, which illustrates the size of the population reached by the media properties of the largest corporations within the shelter category, indicates the extent of that success. Profitably meeting and conforming to values institutionalized in shelter category media have become dominant incentives driving development in certain North American urban typologies, particularly in suburbia, but increasingly also in urban centers. And the core value so institutionalized — equity creation — is value itself.

[An image from Designed to Sell, a show which takes homes not ready to be on the market, gives designers a $2,000 budget, and applies pastiche in the form of paint, textures, accessories, and re-arranged furniture to maximize its selling price. At the time of this shot, the designer remarked “And you know what? All of these things add value – so we’ve done them.” ]

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Equity HGTV simultaneously creates incentives that drive development, while providing a means for understanding existing incentives. By indexing key tactics and trends promoted by HGTV, investigating their effect on city and suburb, and tracing demographic data about home expenditures, we can critically examine the demand HGTV creates and exposes. This equity-urbanism, an urbanism constructed around the cultural valuation of home-ownership, is at its core a relentless appropriation of ‘home’ as ‘wealth creator’. If Gottfried Semper updated his Four Elements of Architecture to accurately represent the contemporary American condition, hearth, roof, enclosure and mound would have to be supplemented by a fifth: ATM.

Tactics and Trends The effects of HGTV, shelter category media, and equity urbanism on architecture and cities are best understood in terms of tactics and trends. Tactics are architectural methodology, while trends are both produced and reinforced, occurring in both architectural and urban manifestations. The tactics and trends described here are all promoted, produced, and reinforced by HGTV in particular, though most are shared by shelter category media in general and driven by the American culture of home ownership and its pursuit of equity.

1. Pastiche The central architectural tactic promoted by HGTV, as well as many other shelter category media outlets, is pastiche. As an architectural methodology, pastiche consists primarily of exploring how cosmetic alterations and retail purchases can be optimally arranged in, added to, and subtracted from a home. A good home does not necessarily support the lifestyle of its occupants: a good home shows well. Indeed, custom touches, like a built-in sushi bar (3), are strongly discouraged, because the most important resident of a home is the next one. And if he and his wife want to see tray ceilings, built-in closets, built-in cabinets, more accessories, framed mirrors, real stone veneers, fake stone floors, new furniture layouts, an outdoor fireplace, a new swimming pool or matching towels, as HGTV assures you they do, then you’ll provide them, or risk falling behind in the equity arms race.

Pastiche seems innocent enough, if somewhat superficial, but implicit in this methodology is the notion that the ordinary single-family home on a suburban tract is a perfectly adequate, even desirable, starting point. It may need to be properly decorated and presented, but both the structural and organizational architecture of that home, as well as the dominant patterns of suburbanization which it lies within, are sheltered from substantive critique by a wall of rapid-fire superficial criticisms. HGTV experts like Mike Aubrey or Antonio Ballatore may slam the tile choices in your second bathroom, but they’ll never question your need for a second bathroom, or ask you to consider the impact of your lifestyle choices on the city in which you live.

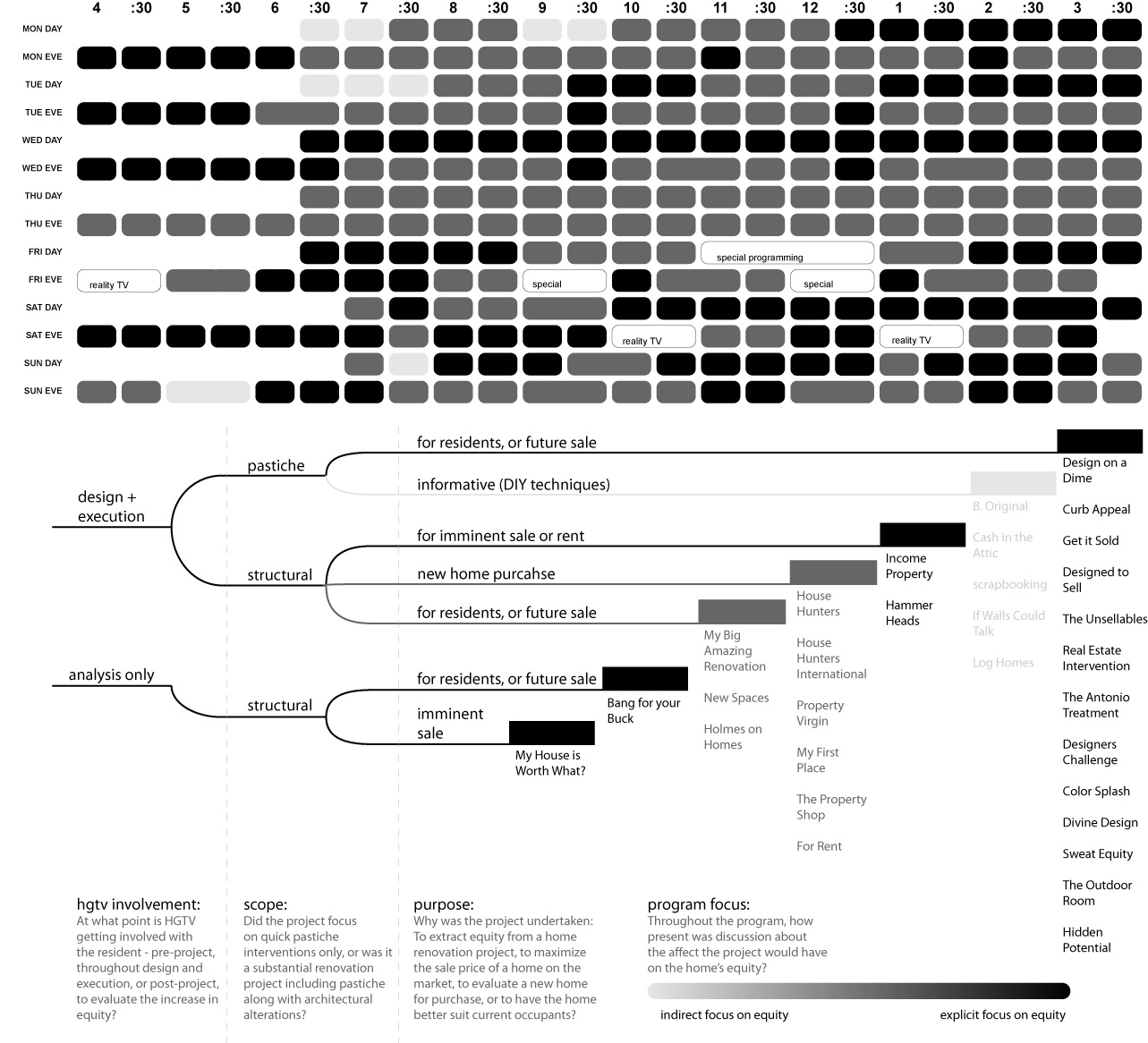

[Figure 2: An analysis of HGTV’s programming demonstrates the emphasis placed on programs which discuss, to varying degrees, the effect of their recommended renovations and techniques on a home’s equity. Programming is broken down by: the point at which HGTV becomes involved in the project, the scope of the work, the purpose of the project or show, and the extent to which equity was discussed during the program.]

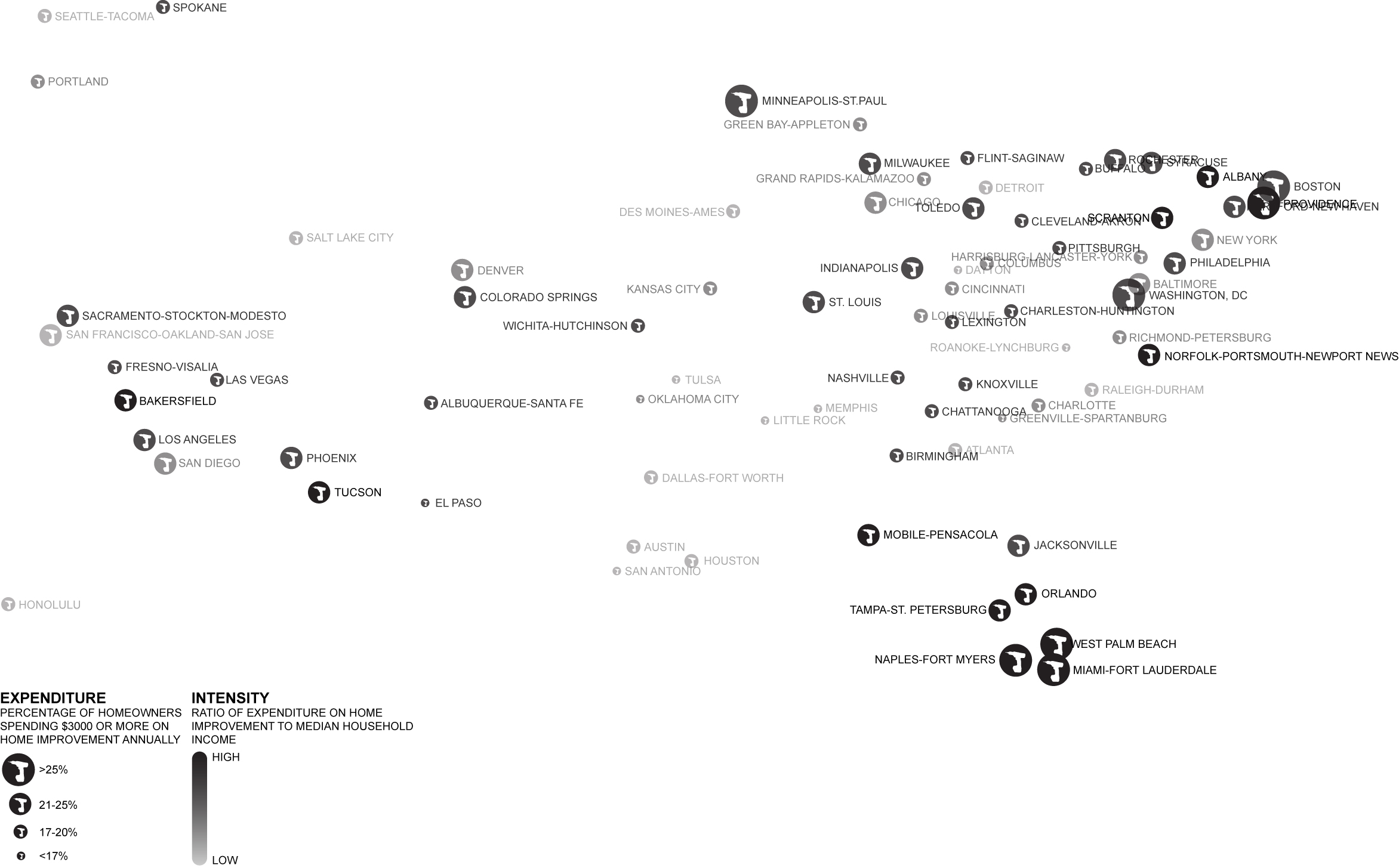

[Figure 3: This map indexes the location and intensity of expenditures on home improvement in most major cities in the United States, using data from 2007. California, Florida, and the Northeast are the regions with the greatest concentration of such expenditures.]

2. More bathrooms! More bedrooms! This tactic is straightforward, but vital to the creation of equity. Despite the love for open floor plans professed by virtually all of HGTV’s experts, those same experts are — contradictorily — equally fond of subdividing the interior of the home. Subdivision adds tick marks to indexed categories — number of bathrooms, number of bedrooms — in a real estate ad on the Multiple Listing Service (MLS), one of realtors’ primary resources for finding comparable homes, and pricing accordingly (4). As the home is subdivided, its floor plan comes to reflect not the logic of living, but the logic of the real estate ad. The desire to optimize the floor plan for the MLS directly challenges the modernist ideal of configurable, multi-purpose space. The value of that ideal is difficult to quantify and sell, unlike the long list of subdivided and highly specific spaces (media rooms, bonus rooms, offices, etc) favored by realtors.

3. Standardization In an equity-dominated urbanism, standardization is encouraged at both an urban scale and an architectural scale. To be an efficient moneymaking machine, the home must conform to the neighborhood price range. Homes too far below the local median reduce the value of surrounding homes; homes too far above it see their own values degraded. So-called comparable properties (‘comps’) enforce standardization on an urban scale. At an architectural scale, standardization produces reliability, a key marker of a valuable investment. Standardization thus produces the remarkable ubiquity of the standard neo-traditional suburban home across vast distances (from Long Beach to Long Island) and staggeringly disparate terrains (from the limestone sinkholes of Florida to the deserts of Arizona and back to the temperate pine forests of North Carolina), which would seem to call for unique and varying architectural responses.

An interesting relationship also exists between standardization and pastiche. Standardization brackets a range of values between which a homes fluctuate in a market. But within this range, home-ownership is an exercise in increasing value, and pastiche is the tactic of choice, precisely because its superficial character prevents it from pushing homes outside the bracketed range.

[Before and after images of a home on Curb Appeal, a program which re-designs only the front exterior of a home in order to raise its ‘curb appeal’, and thus its potential re-sale value.]

4. Suppression of Novel Agendas Standardization is accompanied by the suppression of dissident styles, ideas, ethos, and technologies. Why wasn’t Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome house, for instance, widely adopted? Is it because no one wanted it, or is it because everyone thought no one wanted it? When the faceless and unknowable next resident is a silent partner in any home purchase or improvement project, it becomes extremely difficult to integrate any novel agenda into the culture of home ownership. Options which increase equity are tightly bracketed: you might fervently believe in the worth of a novel architectural idea or new technology, but can you count on your home’s future buyer having an equal valuation?

As an example, sustainability and energy efficiency have only recently begun to strongly impact residential architecture with the emergence of a reliable market for them. You might value the $50,000 photovoltaic system you’ve just installed in the house, but unless you plan on living in that house for the quarter century it will take to recoup that investment through energy savings, you are dependent on the next buyer agreeing with your valuation of that system in order to maintain your equity. HGTV’s representative realtors advise homeowners to make purchases and additions with the clearest, highest, and most certain return-on-investment, not those which have potential social or environmental benefits but are riskier financially.

Furthermore, many novel architectural agendas may in fact reduce the economic value of homes. While some agendas — such as the “New Urbanist” movement — have explicitly promoted their functional compatibility with building equity through home ownership, others — such as the “small house” movement — are equally explicitly incompatible. Whether a novel agenda is actually incompatible with equity-based urbanism or merely perceived by the home-buying public as such, the effect — suppression — is the same.

5. Citizen Realtors Another trend produced and reinforced by HGTV is the de-professionalization of the real estate occupations — realtors, developers, interior decorators, etc. — and the corresponding rise of the amateur realtor. Shows such as Bang for Your Buck and Curb Appeal feature rotating casts of professional realtors who tour the homes featured on the show, dispensing commentary on what will “show well”, seduce buyers, and improve market value. As they do so, they inculcate viewers with professional lingo and tactics, training homeowners to react to homes like realtors. While it is easy to assume that the arrangement and architecture of the typical suburb is the fault of risk-averse, profit-hungry developers, this forgets that every homebuyer is a developer.

[An image from the show Income Property, which pairs an HGTV designer, Scott McGillivray, with a homeowner who wishes to convert an unused attic, guest house, or basement into rental space. McGillivray develops 2-3 alternative designs at various price points, and evaluates them with the owner in terms of initial cost, expected rental value, and increase in home equity.]

6 For the floor plan and a walkthrough of 2010’s Dream Home, click

7 Companies which had products placed in the home as well as commercial time purchased for this year’s Dream Home included: Ethan Allen Furniture, Subzero, Wolf Cooking Equipment., Lumber Liquidators, Intuit Business Software, Omni TV, Dawn, Shermin Williams, Belgard, Disney, Welborn Cabinets, and Silestone.

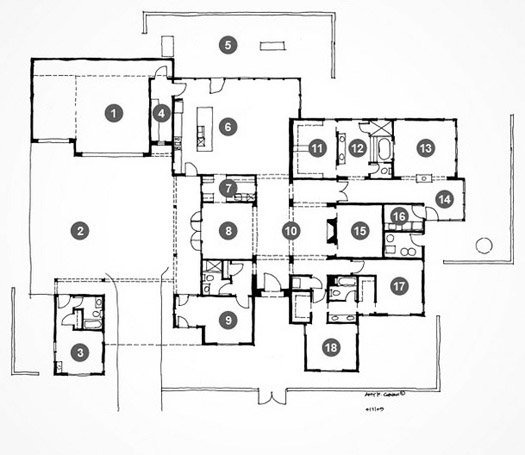

6. The Dream Home Once a year since 1997, HGTV designs, builds and gives away its ‘Dream Home’. This house – essentially the embodied Platonic form of HGTV’s architectural tactics — is more than just a home, it is an architectural wrapper for aspirational resort living (5). Though it is covered by the finest pastiche HGTV’s top designers can muster, the dream home has the same structural and organizational architecture as an average suburban home (6). This makes a great deal of sense, as the aim of HGTV is not to push architectural boundaries, but to provide an appealing platform for the home’s product and advertising sponsors (7). The Dream Home is an extended infomercial, so it is critical that viewers be able to envision themselves within it, that only the quality of the pastiche (the Wolf kitchen appliances and the Silestone quartz countertops) distinguishes the Dream Home from their homes.

[HGTV Dream Home 2010 floorplan, courtesy of HGTV.com]

The premium HGTV places on meshing the Dream Home with viewer expectation makes it an instructive window into the culture of home ownership. The 2010 Dream Home, which was first revealed in a marathon broadcast on New Year’s Day, echoes many of the themes that run throughout HGTV programming. Turning the home, particularly the master suite, into a personal retreat is described as a defining quality of the home’s dreaminess, as are open floor plans and ample window area. Whirlpool tubs with candle-holders, custom-tiled kitchen backsplashes, and (of course) ample closet-space abound.

But, the Dream Home is just as instructive for what it is not. First, it is not appropriate for people who don’t work from home, as it is located too far from New Mexico’s major employment centers for reasonable commuting. Viewers of HGTV do not dream of carless lifestyles, but of secluded resorts. Second, despite what those in the building industry describe as a sudden and massive demand for ‘green building’ and ‘sustainability’, there is no effort to engage those movements. Given the high cooling bills typical of New Mexico, it is surprising that there was no discussion of energy efficiency, electrical bills, cooling — not even a nod toward the insulating properties of the floor to ceiling windows. A cynic might suspect that this is because a window manufacturer interested in sponsoring the home could not be found, but the absence of such discussion is notable regardless of the reason for it.

An Embedded Feedback Loop These six tactics and trends — dependence on pastiche, the subdivision of the interior of the home, standardization, the suppression of novel agendas, the rise of citizen realtors, and aspiration towards the Dream Home — all reflect the intimate relationship between HGTV and the cultural forces which inform the American ideal of home ownership. There is, it should be said, nothing particularly new about this ideal. Walt Whitman wrote that “a man is not a whole and complete man unless he owns a home and the ground it stands on”, and Americans have taken Whitman’s advice to heart, as over two-thirds of Americans are homeowners (8). HGTV and other Shelter Category media reflect this deep, underlying cultural stance, but they also enforce and expand upon that valuation. They are both a consequence of America’s ownership culture and a producer of the values of that ownership culture, in an embedded feedback loop where cause and effect can’t easily be pried apart.

As the tactics and trends of HGTV reveal, ownership culture is ultimately not founded on the rationales of personal responsibility, security, or stability, but upon the notion that the home is an asset for the cultivation of personal wealth. Architecturally, this is a strange notion —the home as a wealth generator, not shelter – but it does a great deal to explain the dominance of the primary architectural forms of contemporary America, the cheaply built urban condo and the even more cheaply built suburban home. The notable thing about both these architectural forms is how unengaged architects are with them: both in that most critical discourse is unconcerned with mass-produced housing and in that mass-produced housing is produced with very little input from architects. (9)

HGTV and other shelter category media ultimately present a direct challenge to the relevance of architecture. Though the very title of this media category — “shelter” — would seem to reinforce the importance of shelter as the central function of the home, the media content consistently undermines that understanding. If homes now exist to generate wealth, not to provide shelter, then architecture, whose most fundamental disciplinary territory has always been the provision of shelter, faces an identity crisis.

Thus the shelter category’s unending focus on consumer goods, simple do-it-yourself fixes, and faux finishes challenges not the artistic integrity or the theoretical stances of architecture, but the usefulness of architects to a mass culture which no longer understands the home in the same way that they do. Architects shouldn’t be afraid of HGTV because of what it gets wrong, but because of what it gets right. It signals a chasm between what architects do and what people care about.

Crash In December of 2008, Standard & Poor’s Case-Shiller Composite Ten price index, the premier tracker for American residential real estate sales, which tracks market performance in Boston, Chicago, Denver, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, South Florida, New York, San Diego, San Francisco, and Washington, reported the most severe annual fall in its history, an astonishing 19.1%. (10) Looking back from December of 2009, that market — now understood to be a bubble fueled by cheap credit and unsustainable speculation — had peaked between 2005 and 2006, depending on the measure used, and entered a death spiral that has yet to relent.

This crash, accompanied by an equally severe implosion within the shelter category media, as indicated in Figure 1, presents a direct challenge to the foundational assumptions of equity-urbanism as well as a clear opportunity for critical engagement with the assumptions and tactics of the shelter category. If we believe that an equity-focused “real urbanism” is bubble urbanism, founded on unrealistic expectations about real estate appreciation and incapable of sustaining the kind of growth in real estate prices which fueled the growth of the shelter category at the beginning of the decade, then this is the moment in which an engaged and honest critique of those assumptions and tactics will find the most fertile ground and the most open minds.

[…] Read the rest of the piece “Shelter Category” (here) […]

Man great work guys.

Architects shouldn’t be afraid of HGTV because of what it gets wrong, but because of what it gets right. It signals a chasm between what architects do and what people care about.

In light of this, what should or can architects do? It seems that more than architectural interventions are needed. Perhaps a cultural/economical one?

Or maybe that is what the crash was? Perhaps, driven in fact behind the scenes by a couple of political architectural activists?

Your point about the Dream Home not emphasizing/having any sustainable features is curious, because I too have heard from a variety of sources how in demand green buildings are…

But then i don’t really run with the HGTV crowd..

I thought this was a perfect statement.

“As the home is subdivided, its floor plan comes to reflect not the logic of living, but the logic of the real estate ad.”

Nice work all around! Very logical and timely point of departure (the home is a machine for making money, not living) and thorough and thoughtful analysis.

The emphasis on standardization, pastiche and equity (assumed value) rings particularly true especially given that money is the ultimate representation of those themes.

It has me wondering about a couple of things.

–mammoth mentioned that the “the primary function of the home in America is, ironically, not shelter but wealth creation”. But I wonder if that is really true. Maybe wealth creation is just the most prominent, but shelter is still primary? Of course, a house must function on that level first, right? Even if the main goal is wealth creation and the primary function is sublimated to that? It’s just hard to imagine the suburbanite buying a two bedroom home even thought they have four kids just because it will somehow be worth more (location, or whatever).

-What does this have to do with vernacular architecture? Is this the new vernacular, no longer grounded in materiality and environment and experience but rather in equity, placelessness, pastiche, and standardization? Is it the capitalist vernacular? Am I being ridiculous (totally possible)?

–“An interesting relationship also exists between standardization and pastiche. Standardization brackets a range of values between which a homes fluctuate in a market. But within this range, home-ownership is an exercise in increasing value, and pastiche is the tactic of choice, precisely because its superficial character prevents it from pushing homes outside the bracketed range.”

Well put! It sounds off on the limits of quantitative analysis (at least for me), which lends itself to a discussion about the limits of parametric design in a larger sense (design within and according to a given set of parameters). That is not to say it isn’t useful or interesting…

Thanks for publishing the article here, too!

Yeah i should have said thanks for publishing here too.

Also, faslaync i like this idea. The current “capitalist vernacular” as contemporary American/global vernacular.

[…] the boys at Mammoth in their reposting of their contribution to MONU 12 entitled the Shelter Category dissect the contemporary HGTV […]

Thanks for the kind words guys. Like Nam, I really like the idea of a “capitalist vernacular”. Of course the thing about a capitalist vernacular would be that its primarily an economic architecture, and so it can assume nearly any aesthetic style, so long as that form is marketable…

But I wonder if that is really true. Maybe wealth creation is just the most prominent, but shelter is still primary?

Yeah, we went with the binary opposition (“Le Corbusier was wrong…”) for maximal provocation, but of course it’s not really that simple. Still, while I (obviously) think that there’s a reasonable case to be made that the architecture of the contemporary American home is more fundamentally driven by its function as wealth-creation mechanism than by its function as shelter, it’s still a house, and houses provide shelter. Which is primary? I’m not sure that answering that really matters; what I think is much more interesting is what that realization — about the home as wealth creator — tells you about why architects have little impact on the dominant American residential typologies. You’re not going to convince a homeowner who’s primarily concerned about his house as an asset to hire you if all you want to talk about is modularity and decorated sheds and whether ornament is crime or not.

[…] value holds little to no weight in our suburbs. With their brief in Magazine on Urbanism called The Shelter Category, we are treated to an analysis of housing culture through the eyes of HGTV (probably the most […]

[…] is the landscaped iteration of the ‘equity urbanism’ that we described in our essay, “The Shelter Category”, that was published in MONU #12: “…ownership culture [and 'equity urbanism' are] […]

[…] probably think this is kind of an odd post, given our frequent arguments for the importance of understanding, working with, and valuing the American suburb. We like to hold these things in tension — esteem […]

[…] American predilection for viewing the home primarily as an investment strategy, which mammoth has previously written about. In both cases, the home’s function as shelter (or machine for living) is subsumed by its […]

Just reread this post. It is excellent.

[…] commodity reminds me of mammoth‘s own ruminations on the American suburban home as a machine for generating wealth — in both cases, the apparently aberrant physical characteristics of the designed object in […]