The following is a guest post from Tim Maly — of the excellent Quiet Babylon — concerning the topic of traffic and The Infrastructural City.

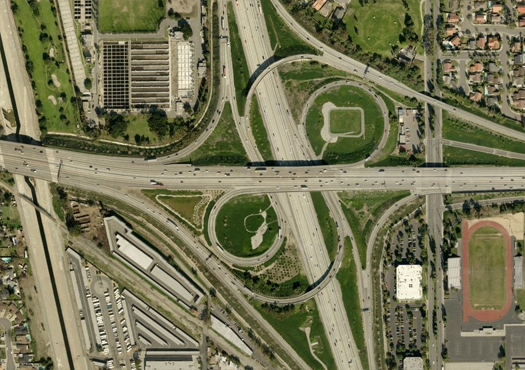

About a year ago, a business trip found me camped out with my laptop in the top floor lounge of a hotel in LA, overlooking the San Diego Freeway. There were windows on all sides affording an excellent view of the road. When I wanted a break, I watched traffic.

As the laconic afternoon gave way to rush hour, the density of cars increased and speeds fell until traffic stopped. Four lanes of southbound commuters were ground to a halt. More cars piled into the back of the traffic jam and it grew northwards. I watched this for awhile, grateful that I didn’t have anywhere I needed to be.

Then the most amazing thing happened.

The jam moved.

I don’t mean that the cars got unstuck and everyone proceeded on their merry way. I mean that the jam itself was a structure in motion. From my window, I could see a zone of total congestion where cars were literally parked. On the upstream end of that zone, new cars were being added all the time as commuters caught up with the stopped vehicles. On the downstream end, cars were being freed up to drive again. It takes time to accelerate and you have to wait for the car in front to start moving. That delay was long enough and the cars in the rear were arriving fast enough that the structure was perpetuating itself.

The traffic jam I could see from the window existed despite the road ahead being completely clear.

What I’d mistaken for the growth of the traffic jam was actually the leading edge of a pulse. It’s called a shockwave jam. It isn’t just congestion, it’s a wave of information, traveling upstream against the flow of cars, carrying with it news about some incident that happened perhaps miles away. Hapless commuters become an unwitting medium, electrons on the wires of the freeway.

This is a truly bizarre emergent phenomenon. To get a sense of how bizarre, take a look at this video released by Japanese scientists, showing the problem reproducing itself on a clear circular track. This should be the canonical demonstration of chaos theory. It should replace the butterfly flapping its wings.

How do you fight that?

There are folk solutions about changing your driving style and a variety of proposed systems that involve handing control of the car over to the road or to ad hoc networks of other vehicles.

The main message here is that you don’t know how to drive your car in traffic. It’s not your fault; you are part of a network of events that spans vast stretches of geography where the slightest perturbation can cause massive sprawling disruption. To have the chance to succeed at this, you’d need to see beyond yourself. You’d need super powers.

It’s impossible to say where the first traffic jam was, but the origin of modern traffic control was probably in 1722 in response to “the great inconvenience and mischiefs which happen by the disorderly leading and driving of cars, carts, coaches, and others carriages over the London Bridge, whereby the common passage there is much obstructed.” To fix matters, the Lord Mayor of London ordered that three able-bodied men be appointed as public servants to keep traffic to the left and keep it moving.

Sean Dockray, Fiona Whitton, Steven Rowell – Blocking All Lanes – The Infrastructural City p.106

I’m reminded of the first surgeons. Unlike our contemporary steady-handed fine-incision-making heroes, they were brutes. They had to be – in order to save someone’s life by sawing off a limb, they had to be quick enough so the patient didn’t die from shock during the procedure. It takes a real butcher’s strength to force your way through bone.

This image of rough and ready public servants manhandling traffic chaos into some semblance of order continues with New York’s first traffic cops in the 1860s. In order to be seen, they were the tallest men in the force. Each of them over 6′, towering over the confusion of the crowd, barking orders and waving traffic along with their hands.

By choosing officers who could literally see further than the crowd and arming them with rules and the ability to enforce them (the ability to think further than the crowd), traffic cops were endowed with the super powers necessary to at least unsnarl local conditions, if not improve the flow of traffic overall. At the risk of stretching a metaphor, they became cybernetic entities. Locally cognizant real-time control systems, inserted to regulate a network that could not regulate itself. I’m thinking here of James Watt’s steam engine with a governor that turned irregular bursts of steam into a smooth flow of power.

Listen to this next passage as traffic cops experience their own micro-singularity.

Problems with this system arose immediately. It was difficult enough for any single officer to coordinate his activities with another officer, one block away, but it was practically impossible for that officer to synchronize his signals with officers at the four adjoining intersections, each of whom might be coordinating with three more intersections, and so on, throughout the urban grid. Over time, the traffic cop was slowly transformed: his hands took on white gloves for visibility; his voice was replaced by a whistle; and eventually, he was elevated in a tower and communicated with the traffic via signs or coloured lights. The police officer slowly vanished, his body evolving into mechanical and electrical devices. His hands were replaced by standardized, colored signals. His eyes were replaced by sensing actuators, such as microphones, pressure sensors, electromagnets, or video cameras. All that was left was to replace his brain.

Sean Dockray, Fiona Whitton, Steven Rowell – Blocking All Lanes – The Infrastructural City p.106

We find ourselves in traffic (never of traffic) buffeted by a system prone to irrational seizures, ordered around by a sprawling network of machines whose decisions are unknown and unknowable. Worse still, we’re sitting in devices that – when they were sold to us – made some very explicit promises about the open road. We were promised independence and instead we got this weird pseudo-freedom where we get to control the car but we are severely limited in where it can go.

So we try to cheat. Aggressive drivers push along shoulders and try to muscle their way back into the flow. Frustrated law-abiding commuters respond by pulling close together to keep them out. We try side streets and alternate routes.

A whole folklore of tricks is passed around. If you flash your lights, it can fool the sensors into thinking that an emergency vehicle is coming, giving you the green. The pressure plate is two car lengths back from the intersection so that a line will form before changing the light. If you stop early, you won’t need to wait for another car. If you have a mannequin, you can take the carpool lane. This route is better on Tuesdays, that route is better on Wednesdays.

The impulse to optimize and the impulse to maintain control are put at odds here. The mythological freedom of the open road gives way to nominal control rendered irrelevant by factual helplessness. Drivers lament that things would be better if only there were less cars on the road. Or more lanes. Both of these wishes are myopic.

The Los Angeles depicted in The Infrastructural City is unwilling to move in either direction. Caught between individualists demanding the freedom of the car and individualists expert in maintaining their property values, the age of heroic infrastructure has ended for LA.

Today’s freeways are clogged in perpetual gridlock. Fixing them is impossible. Any new freeways would be fought by NIMBYist homeowners, but more than that, traffic planners recognize that if new freeways were built, motorists would choose to live further out. After a brief period of time, the freeway would, once again, be jammed hopelessly.

Kazys Varnelis – Introduction – The Infrastructural City p.14

The intriguing possibility is that heroic infrastructure may not be needed to unsnarl LA’s freeways. In a paper called The Price of Anarchy in Transportation Networks: Efficiency and Optimality Control physicists Hyejin Youn, Michael T. Gastner, and Hawoong Jeong discovered that under certain circumstances, traffic conditions can be improved by blocking roads.

We then compare the costs of the Nash flow on the original network with those on networks where one of the 246 streets is closed to traffic. In most cases, the cost increases when one street is blocked, as intuitively expected. Nonetheless, there are six connections which, if one is removed, decrease the delay in the Nash equilibrium… If all drivers ideally cooperated to reach the social optimum, these roads could be helpful; otherwise it is better to close these streets.

Hyejin Youn, Michael T. Gastner, and Hawoong Jeong The Price of Anarchy in Transportation Networks: Efficiency and Optimality Control

There are two intriguing ideas in that passage. The first is the idea that infrastructural problems can be solved in some cases by having less infrastructure. This is an experiment that would be easy to carry out and cheap to do, even in LA.

The second is the idea that the infrastructure problems can be solved not with changing the infrastructure but changing how it’s used – optimizing the network. This idea has been covered before on mammoth. In their best architecture of the decade, Rob and Stephen included the CityCar.

While the technology behind CityCar is interesting in and of itself, architecturally the most interesting aspects of CityCar are the dynamically-priced markets for electricity and roadspace which Smart Cities envision developing around the second, shared use model. Through GPS systems embedded in the cars, congestion pricing could be altered in real-time in response to the flow of traffic through a city’s streets, achieving a far more perfect market reflection of the urban condition than could be imposed by any top-down model… The CityCar, then, is not merely a vehicle traveling across fixed infrastructures (or a smaller version of today’s cars), but is itself a distributed infrastructure, resilient, flexible, and responsive to input from the city.

Rob Holmes and Stephen Becker the best architecture of the decade

Rob and Stephen are quick to acknowledge the pragmatic and regulatory hurdles that these cars (let alone any automated driving system) face in seeking mass adoption. But these sorts of things can proceed piecemeal. Car makers are already putting sensors in their vehicles for collision safety, OnStar assistance etc. And it doesn’t seem like such a big leap to go from automated toll systems like E-Zpass to highly granular congestion pricing schemes.

Besides, if traffic cops can experience a micro-singularity, why not drivers?

Over time, the driver was slowly transformed: her hands took on a steering wheel for better maneuverability; her voice was replaced by a horn; and eventually, she was sealed in a cabin and communicated with the traffic via honks or coloured lights. The driver slowly vanished, her body evolving into mechanical and electrical devices. Her hands were replaced by high precision steering mechanisms, her feet by networked cruise control. Her eyes were replaced by sensing actuators, such as GPS chips, proximity sensors, local mesh networks, or video cameras. All that was left was to replace her brain.

[…] The full post is here. […]

Love this post. The whole embodied cybernetics aspect of this chapter really got to me as well…

Very interesting, thanks. Those slugs of traffic are also called “kinematic waves,” and were described by river scientists of all people; see paper here: http://bit.ly/9FyvxO . You’ll learn that tailgating is a big cause of them; if people would just space out a bit, the jams wouldn’t be so severe.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Andrew Fitzgerald, Bradley Wayne Moore. Bradley Wayne Moore said: "All that was left was to replace her brain." http://m.ammoth.us/blog/2010/06/driving-blind/ by @doingitwrong #mammoth […]

I read this yesterday, and thought I would try an experiment, because I have often noticed the whole ‘shock wave jam’ effect on a smaller scall as I drive home. Auckland traffic is very stop start and you can see the mini jams rolling back throught the traffic.

So I drove home at 20 Kph (once I hit traffic, I’m not a total jerk). And I maintained that speed the whole way home.

Of course I didn’t get home any faster, but I also never stopped. And the same car that I started out behind, I ended up behind so I lost no ground.

I was pretty hard to stay disciplined as the cars ahead of me took off hundreds of metres up the road, only to sit there until I almost ran up their arse.

It would have been interesting to see how the traffic behind me was affected (I probably just raised blood pressure).

Josh, next time you should do it with a friend trailing you by 3 minutes to see if laminar flow was maintained. If someone wishes to subsidize my trip to New Zealand, I’m happy to volunteer myself for this bit of science.

[…] a new kind of stratum, born after all the large-scale developments of the times of urban sprawl, as highways, oil pumps or dams and pits. As they pointed “Like the freeways before them, wireless networks […]