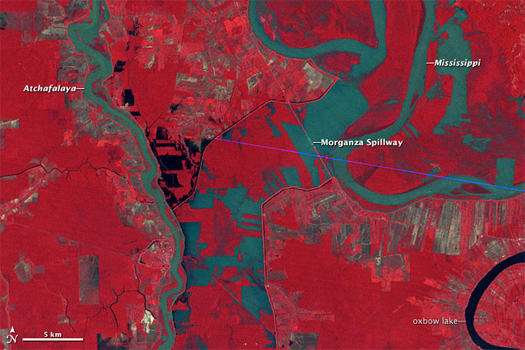

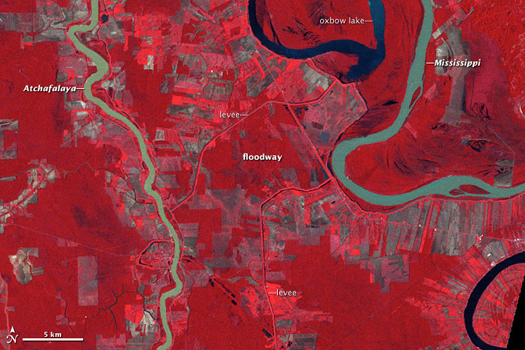

[You may recall that our posting on floods began with an image quite like the two above. That first image was, like these two, a false-color satellite image of the open Morganza Spillway; but where the first image was taken in May, the two above were taken on May 5, 1973 and April 6, 1977 (respectively) — May 5, 1973 being only other time that the Morganza Spillway has been opened. In 1973, intense flooding on the lower Mississippi threatened to overwhelm the Old River Control Structure (as well as downriver levees), and the Spillway was opened.]

[Aerial view of the opened spillway, May 1973.]

In “Atchafalaya” — our Mississippi floods ur-text, from The Control of Nature, John McPhee writes:

“Every shopping center, every drainage improvement, every square foot of new pavement in nearly half the United States was accelerating runoff toward Louisiana. Streams were being channelized to drain swamps. Meanders were cut off to speed up flow. The valley’s natural storage capacities were everywhere reduced. As contributing factors grew, the river delivered more flood for less rain. The precipitation that produced the great flood of 1973 was only about twenty per cent above normal. Yet the crest at St. Louis was the highest ever recorded there. The flood proved that control of the Mississippi was as much a hope for the future as control of the Mississippi had ever been. The 1973 high water did not come close to being a Project Flood. It merely came close to wiping out the project.

While the control structure at Old River was shaking, more than a third of the Mississippi was going down the Atchafalaya. If the structure had toppled, the flow would have risen to seventy per cent. It was enough to scare not only a Louisiana State University professor but the division commander himself. At the time, this was Major General Charles Noble. He walked the bridge, looked down into the exploding water, and later wrote these words: “The south training wall on the Mississippi River side of the structure failed very early in the flood, causing violent eddy patterns and extreme turbulence. The toppled training wall monoliths worsened the situation. The integrity of the structure at this point was greatly in doubt. It was frightening to stand above the gate bays and experience the punishing vibrations caused by the violently turbulent, massive flood waters.”

If the General had known what was below him, he might have sounded retreat. The Old River Control Structure—this two-hundred-thousand-ton keystone of the comprehensive flood-protection project for the lower Mississippi Valley—was teetering on steel pilings above extensive cavities full of water. The gates of the Morganza Floodway, thirty miles downstream, had never been opened. The soybean farmers of Morganza were begging the Corps not to open them now. The Corps thought it over for a few days while the Old River Control Structure, absorbing shock of the sort that could bring down a skyscraper, continued to shake. Relieving some of the pressure, the Corps opened Morganza.”

We’ll return to the Old River Control soon.

I tell you I read that John McPhee article on the Atchafalaya when the Atlantic first linked to it last month.

That is one amazing piece of long form journalism at it’s finest!

But oh so long…. It was so great though I printed it out so my room-mate a geo-technical lab manager could read it.

[…] an interrupted series, which properly begins with a series of Atchafalaya-related posts from June: 1973, morganza floodway, and red river landing. I'm going to try to avoid repeating things already […]