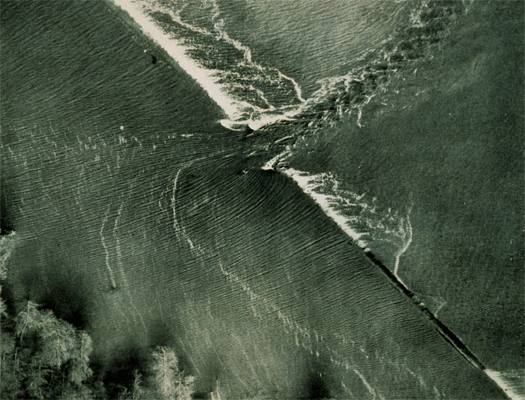

[Mound Crevasse; the explosive force of the 1927 levee break remains visible in the blast-like pattern of lakes and shredded terrain that is clearly visible in this current satellite image.]

If you look closely at the Army Corps’ map of the 1927 Mississippi floods from a couple posts back, one of the major patterns that emerges is that virtually all the flooding is on the western side of the river. (This is in part because snowfall during the winter of 1926 and rainfall in the spring of 1927 was concentrated to the west of the river, though it was also heavy in the Ohio Valley. It is also because the most populated portions of the Mississippi River Valley lay to the east of the river, and so levee construction and emergency flood protection efforts concentrated on the east side.)

One major exception to this general rule is apparent, though, a massive blotch of flooding covering some five thousand square miles of Mississippi, stretching south and east from the river town of Greenville. This is the result of the Mound Crevasse.

[Mound Crevasse, immediately after the levee breach.]

When a levee fails through structural disintegration (which often takes the form of undermining by floodwaters) rather than overtopping, it fails at a specific point. That point is called a crevasse. (As mentioned previously, crevasses can also be created intentionally to produce emergency floodways.)

On the morning of April 21, 1927, an Army district engineer wired the head of the Army Corps of Engineers:

“Levee broke at ferry landing Mounds, Mississippi eight a.m. Crevasse will overflow the entire Mississippi Delta.”

While engineers and Delta planters had long known Mounds Landing was a vulnerable point on the levee system, no one expected a disaster of this magnitude. Of all the breaches along the Mississippi, this would be the worst levee break of the entire flood. In fact, it is still noted as the worst levee break anywhere in the United States.

Four hundred and fifty men had worked through the night in a desperate effort to save the levee, but the river rose too fast. One worker recalled, “It was just boiling up. The levee just started shaking. You could feel it shaking.” In the early hours of the morning small breaks started to appear. Fifteen hundred additional men were rushed to the site, but their efforts could not save the levee. What had begun as a small break quickly became a raging river. Guards forced the African American laborers to keep filling sandbags at gunpoint, but everyone there could feel that the levee was about to collapse under their feet. Sandbags started to wash away, the river ran over the top of the levee, and men took off as fast as they could run. As the levee collapsed, many of the workers were swept away. Soon every fire whistle, church bell and mill whistle rang out to warn the county.

The force of the torrent was unstoppable, scouring out the land and uprooting everything in its path. Trees, buildings, and even railroad embankments were washed away in moments. Even Egypt Ridge, so named because no flood had ever reached it before, was soon engulfed. For 60 miles east of the crevasse and ninety miles south there was nothing but water. Where farms and towns had been, it looked like an ocean. Seventy-five miles away, in Yazoo City, the water was high enough to cover the roofs of homes. In a matter of days, 10 million acres of land would be under 10 feet of water.

The river poured through the break with a force greater than that of Niagara Falls. (Footage of the levee breaks from 1927 — archived in the American Experience program “Fatal Flood” quoted above, can be seen here.)

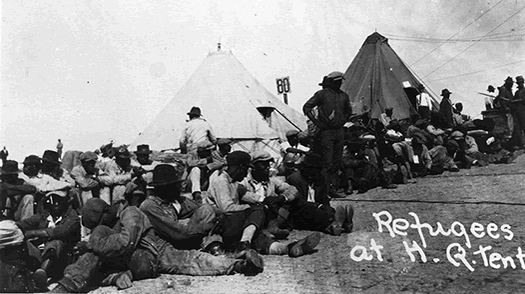

[Refugees near Greenville were forced to live on the river levee — the racist planters in charge of relief efforts for people driven out of their homes in Greenville feared that “if the blacks got out of the Delta, they would never return” (to pick cotton for the planters), and so they forced them to remain in a seven-mile long encampment on the levee. “Black men were not allowed to leave–those who tried were driven back at gunpoint by the National Guard.”]

The Mound Crevasse was responsible for much of the most destructive flooding that occurred in the great flood of 1927. Nearly one-fifth of the 27,000 square miles flooded that year were flooded by waters pouring through the Mound Crevasse. Tens of thousands were left homeless; nearly two hundred thousand were displaced from their homes.

“It would take months for the water to recede. Five weeks after the levee collapsed, engineers surveying the crevasse found waves still as high as 12 feet and water deeper than 100 feet.”

As evidenced by the photograph at top, though, a crevasse does not disappear when the floodwaters recede — or even after the levee is rebuilt. The gouging force of the Mound Crevasse left behind the depressions that became the eponymous lake and its smaller subsidiary, Grassy Lake, while the sedimentary expression of a crevasse is termed a crevasse splay deposit. As a crevasse is an example of the reassertion of geological forces over and against the human control of nature, and, it is a perfect example of the infra-natural disaster. Levee crevasses did not happen before flood control infrastructures were built, and cannot (by definition) exist apart from the intersection of infrastructure and natural disaster. Where levees have held back the slow movement of the river as a geological force, a crevasse releases that tension quickly and at great concentration; when geological forces are compressed into a human time scale, the resulting disaster can be amplified. This — compression and amplification — is a common characteristic of the infra-natural disaster.

Infra-natural disasters are also inevitably political. Unlike the natural disaster, the damage caused by an infra-natural disaster has been channeled by the decisions someone somewhere made, and that means that both there is someone to blame for them (witness Katrina) and that — this is particularly apparent in the case of Mounds Crevasse — they have a tendency to become intertwined with other socio-political events. The flood waters pouring through Mounds Crevasse paid no attention to the color of owners of the homes it destroyed; but, as noted above, the massive racial inequalities which dominated Mississippi politics at the time made the period after the flood even more awful for blacks than it was for whites. (Even when Hoover, prior to his election as President, appointed a commission to investigate allegations about the abuses at the levee camps and the commission substantiated the claims made, the findings were suppressed.)