The next week or two will be dedicated to floods.

This may be entirely obvious, but I think it is worth beginning by noting that floods are not good, and floods are not fun. We’re not talking about floods because we enjoy flooding. Floods are, however, a constant — as we are reminded by the current Mississippi floods, which will be remembered by history along with the floods of 1927, 1983, and 1993 as one of the Great Mississippi Floods. Despite their constancy, floods are often (like the infrastructures we build to control them) out of sight and out of mind. The aim of our posting over the next week or two, in so far as it has a single aim, will be simply to remember, to see, to be aware of floods.

That said, there are a couple of themes I expect to return to. (The posts in this series are, for the most part, as yet unwritten, so I also expect to find some unexpected themes.) Both of these, conveniently, can be found in nascent form in Alexis Madrigal’s recent and excellent “explainer” on the current Mississippi floods at the Atlantic Online.

First, unlike (for instance) the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which preceded (and instigated) the Flood Control Act of 1928 and the subsequent fortification of the Mississippi, both the current Mississippi floods and most contemporary floods elsewhere are not natural disasters, but infra-natural disasters. That is, the natural systems which produce floods are now so thoroughly intertwined with infrastructural systems that it is inappropriate to speak of them separately, or at least to speak of them without acknowledging the role of infrastructures in directing, mitigating, exaggerating, and otherwise affecting the paths of floodwaters. (This is particularly true now that the issue of flooding is so tied to the issue of climate change, the most geographically comprehensive way that humans have altered and are altering our environment. Flood protection infrastructures can also be said to be climate defense systems.)

Madrigal drives home this point in the introduction to his piece:

“What is the Mississippi River? It’s not actually a silly question. The Mississippi no longer fits the definition a river as “a natural watercourse flowing towards an ocean, a lake, a sea, or another river.” Rather, the waterway has been shaped in many ways, big and small, to suit human needs. While it maybe not be tamed, it’s far from wild — and understanding the floods that are expected to crest in Louisiana soon means understanding dams, levees, and control structures as much as rain, climate, and geography. From almost the moment in the early 18th century when the French started to build New Orleans, settlers built levees, and in so doing, entered into a complex geoclimactic relationship with about 41 percent of the United States.”

Second, as this is a blog about spatial design, we are particularly interested in how designers react to flood conditions. Whether at an urban, regional, or site scale, there is one particular principle that is key to design for floods, which, again, Madrigal touches on:

“Under flood conditions, the best way to take pressure off a place downstream is to let water flow upstream.”

Though a simple statement — and one that flood engineers have always been aware of the import of, as flood control plans have always involved making choices about where to let rivers overflow their banks and where to maintain barriers — there has been an important shift in the way that this statement guides design for floods, as the orthodoxy of storm-water management is gradually moving away from striving to move water quickly and towards slowing the movement of water as much as possible.

As author Scott Huler notes in his tour of typical American infrastructures, On the Grid, this shift “involves making a complete about-face from traditional practices. Instead of getting water to go somewhere else, engineers now do everything they can to keep the water where it is”. In place of a “simple mechanical process of nuisance removal”, he says, “stormwater infrastructure has become a biological process of resource management”. Under flood conditions, of course, the primary locus of concern shifts from management stormwater as a resource to mitigating the damage caused by extreme excesses of water — but the transition that Huler identifies from hard, fast, mechanical infrastructures towards soft, slow, biological infrastructures is indeed underway, to at least some degree, for both general stormwater and flood infrastructures, and will be a repeated theme of some of the design proposals we hope to look at.

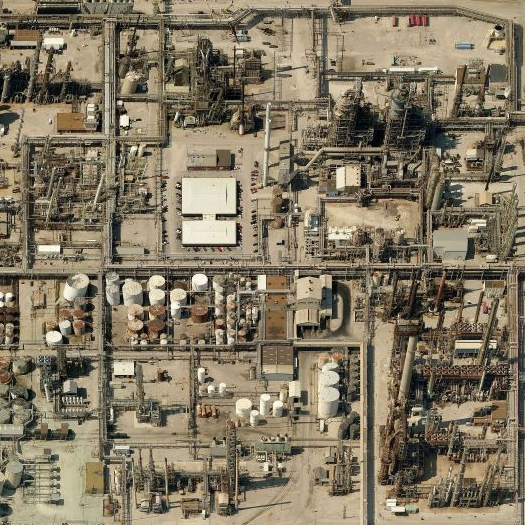

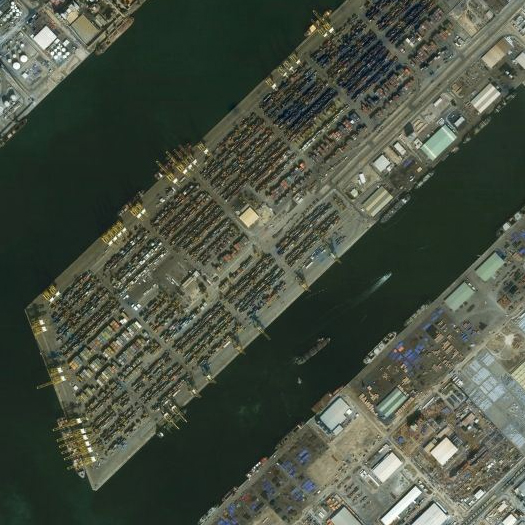

[Thanks to Tim Maly for the link to Alexis Madrigal’s post. The image at the top of the post is a false-color satellite photograph, taken on 11 May, of the Morganza Spillway, which lies between the Mississippi (curving to the east on the right side of the image) and the Atchafalaya (on the western side). “The floodway, designed to reduce water levels in the Mississippi during emergencies, was last open from April 19 to June 13, 1973, the only time it has ever been opened.” I expect to discuss the Morganza further.]