There’s nothing particularly original about the observation that the Dutch have a peculiar national relationship to their landscape (and, in particular, its hydrology), but that peculiarity produces endlessly fascinating oddities and, apparently, endless mammoth posts on Dutch hydrology. As lewism noted on one such post, Bulwarks and Flux:

…the whole of Dutch landscape and history can be seen as a kind of resistance to and acknowledgment of the sea. The polder system, which is on the surface just a land reclaimation sytem, is for a Dutchman something more… a political sytem, an ownership structure, a landscape…

One of those oddities, the Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie (alternately known in English translation as the New Dutch Water Defense Line and the New Dutch Inundation Line), is the subject of this post.

The original Dutch Water Line (whose function and mechanism can be easily dervied from the variables in the English translation, “inundation line” and “water defense line”) dates to 1629, when Prince Frederick Henry, inspired by the successful use of flooding as a defense mechanism during the Dutch War of Independence, began to execute a plan to construct a “line of flooded land protected by fortresses”:

Sluices were constructed in dikes and forts and fortified towns were created at strategic points along the line with guns covering especially the dikes that traversed the water line. The water level in the flooded areas was carefully maintained to a level deep enough to make an advance on foot precarious and shallow enough to rule out effective use of boats (other than the flat bottomed gun barges used by the Dutch defenders). Under the water level additional obstacles like ditches, trous de loup and later barbed wire and mines were hidden. The trees lining the dikes that formed the only roads through the line, could be turned into abatis in time of war. In wintertime the water level could be manipulated to weaken ice covering, while the ice itself could be used when broken up, to form further obstacles that would expose advancing troops longer to fire from the defenders.

This national defense system of weaponized artificial hydrology proved remarkably successful during the 17th century, halting Louis XIV’s invasion of the Netherlands, but less so in the 18th, when the French took advantage of winter ice to bypass the Water Line.

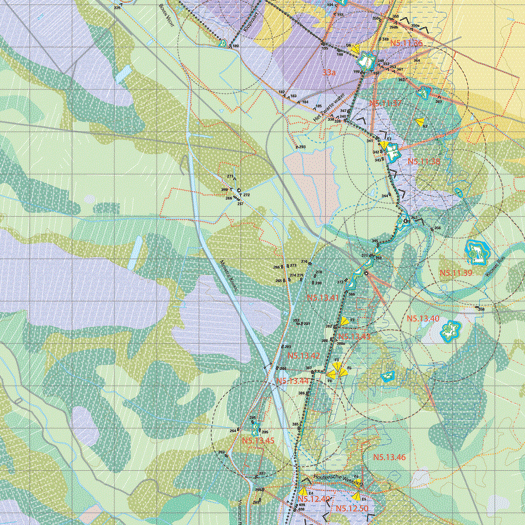

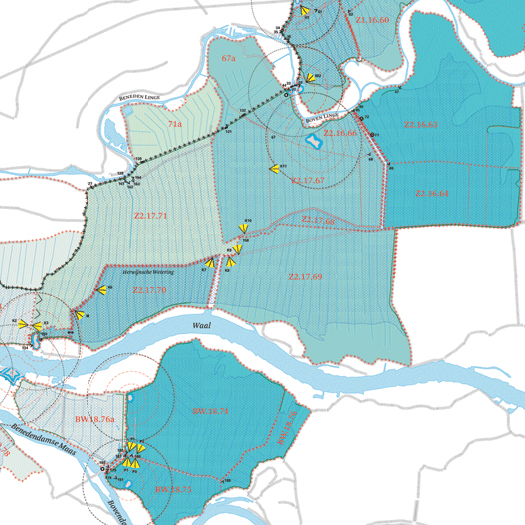

The idea of weaponized hydrology was firmly ensconced in the national consciousness, though, and, after the formation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in the early 19th century solidified national borders, the Nieuwe Hollandsche Waterlinie was constructed to the east of the original Waterlinie. Between three and five kilometers wide, the zone of potential inundation stretched “approximately 70 kilometres from Muiden (situated on the Zuiderzee, currently Ysselmeer), past the city of Utrecht towards the east, down to the large river district (the Nieuwe Merwede) and the Biesbosch,” at a depth of 35 to 50 centimeters (just deep enough to prevent crossing with artillery, but not deep enough for boats) — approximately one hundred and seventeen thousand cubic meters of ominously empty space, imbued with military potential:

The system consisted of 6 what is termed inundation basins, which could be regulated by dikes, culverts, canals, fan locks, dams and sluices. A system of defences, such as forts (covering 2 hectares to 32 hectares) was located at the accesses to the inundations, e.g. near higher roads, or where the inundations could be traversed via existing dikes, lakes or rivers and wherever it was necessary to protect the inundation facilities. There were more than 60 defences of varying types in this Inundation Line. Civil and military roads (available for civil use during peacetime) were also a part of the Inundation line. Planting of the defences was strictly regulated. The permanent defences varied from simple earthworks without permanent buildings to earth defences with brick turrets, ‘turret forts’, bomb-proof barracks, guardhouses, casemates and bomb-proof shelters for artillery…

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the fortifications that sat along the Waterlinie gradually grew in thickness and armament, mirroring increases in the potency of field gun and artillery technology. Care was taken to blend these fortifications into the landscape, in what might described as a landscape architecture of military concealment:

This [concealment was accomplished] by presenting low and vague contours for the defense works when looking from east and south directions. They used ground covering and also bushes and trees of the same kind as in the surrounding landscape. Existing tree lines were extended to cover fortresses.

In World War II, though, the Waterlinie proved unfortunately obsolete, as German forces parachuted behind the Waterlinie to seize key objectives, including bridges into the heart of the Netherlands, and forced Dutch surrender through the devastating aerial bombardment of Rotterdam, in both cases bypassing the Waterlinie. Though there was some attempt at reconstituting the Waterlinie during the fifties as a barrier to Soviet invasion (enhanced by the deployment of anti-aircraft weaponry), the Waterlinie have now all passed in obsolesence.

For the most part, their contemporary fate is that typical of most obsolete fortifications, serving as interesting but relatively obscure tourist attractions. More recently, land artist Agnes Denes was apparently engaged to develop a master plan for the Waterlinie “incorporating water and flood management, urban planning, historical preservation, landscaping, and tourism,” the specific contents of which are listed as an “Inundation Map; Proposed Forestations; Proposed Windmill Locations; Present/Proposed Wildlife Preserves, Wildflower Meadows and Gardens; and Proposed Crystal/Glass Fort” (the last of these is rather unfortunate and can be seen here). While I haven’t found any detailed information on Agnes’s proposal, I’d like to think that a more interesting and significant future (than as permanent tourist attractions) is possible, emphasizing the uniqueness of a corridor in which the Dutch inverted their traditional relationship with the sea, building canals and sluices not keep the water out, but to let the sea in.

[awareness of the existence of the New Dutch Water Defense Line via Kosmograd’s recent post highlighting the gorgeous atlases produced by Dutch (graphic) designer Joost Grootens, whose subject matter include the New Dutch Water Defense Line, the relationship between the northern limits of Roman control in the first couple centuries A.D. and contemporary Dutch urbanism, and a comparative look at 101 of the world’s largest cities; CLUI apparently did some research (file is a pdf, but lacks the extension; you’ll have to save the file and rename it .pdf in order to read it) in 2001 on the Waterlinie, but I haven’t found many details]

[…] the new dutch water defense line – mammoth // building nothing out of something m.ammoth.us/blog/2009/11/the-new-dutch-water-defense-line – view page – cached There’s nothing particularly original about the observation that the Dutch have a peculiar national relationship to their landscape (and, in particular, its hydrology), but that peculiarity… Read moreThere’s nothing particularly original about the observation that the Dutch have a peculiar national relationship to their landscape (and, in particular, its hydrology), but that peculiarity produces endlessly fascinating oddities and, apparently, endless mammoth posts on Dutch hydrology. As lewism noted on one such post, Bulwarks and Flux: Read less […]

[…] has launched their latest project called Bunker 599 + 603. The project lays bare two secrets of the New Dutch Waterline (NDW), a military line of defense in use from 1815 until 1940 (precisely the period without any war in […]

[…] 599 + 603 » révèle l’existence entre 1815 et 1940 de la ligne de défense baptisée la New Dutch Waterline (NDW). Elle a été conçue par Maurice de Nassau puis réalisée par son demi-frère Frederick Henry […]