You’ve arrived at week three of our reading of The Infrastructural City; if you’re not familiar with the series, you can start here and catch up here.

It’s cliche to reference dinosaurs when describing the oil well pumps which are ubiquitous throughout the LA basin, but as a 5 year old obsessed with those prehistoric creatures, there was simply no other way to think about them. I grew up assuming that every place had oil, and along with it, herds of insouciant metal creatures slowly bobbing as they sucked it from the ground. Beyond the mere fact of their presence, though, the wells, pumps and derricks scattered throughout the landscape were rarely a topic of conversation. In this way, my youth mirrors the history of Los Angeles’s conflicted relationship with oil production described in Frank Ruchala’s “Crude City”, the third chapter in The Infrastructural City.

The discovery of oil in Los Angeles — at one time, local production met 20 percent of nationwide demand — catalyzed development of the region by ensuring manufacturers had a supply of cheap energy, spurring the development of the ports, and pumping cash into the economy. Yet Los Angelenos have refused oil equal billing with the other infrastructural triumphs of their city:

… while the Los Angeles aqueduct and the freeways are well documented and have become part of the city’s history, the region’s oil story remains relatively unknown. Although Los Angeles named what is arguably its most famous road, Mulholland Drive, after its chief water engineer, almost none of the region’s hydrocarbon history has been commemorated, much less remembered, even though Los Angeles is so identified with its consumption of petroleum products

“Crude City” is a tour of this contested history, full of fascinating anecdotes. Oil was not only a fuel powering production, but often the material of production. It became the asphalt paving Los Angeles’s roads and freeways, and the plastic spun into hula-hoops. But despite the prevalence of well pumps scattered about the landscape, the true scale of LA’s oil infrastructure was sequestered from public view.

Some facilities are designed to look like regular buildings, such as the thirteen-story Packard drillsite that completely overwhelms its surroundings on Pico Boulevard. Designed in the 1960s to look like a modern office building, the drillsite has done a remarkable job of remaining hidden. Supposedly, two vice presidents of a rival oil company once drove by the building three times before a police officer convinced them that it was really an oil site. The entire structure is made up of steel sound-proof panels. All drilling operations take place indoors, including truck loading and unloading. The massive height of the complex is used to mask the height of the drilling rig which completes the individual wells. The oil wells themselves are found in the basement level of the complex.

Consider the layers of subterfuge described by Ruchala above: this building is imitating other buildings, which are themselves imitating an architectural style; they are meant to conceal structures with incredible detail and character, by impersonating architecture which is meant to lend some measure of personality and character to spaces which would otherwise be devoid of it. It is a strange inversion of the modernist cliche “form follows function” — although almost purely theatrical, this urban theater is a highly functional response to our society’s contentious mental relationship with oil extraction.

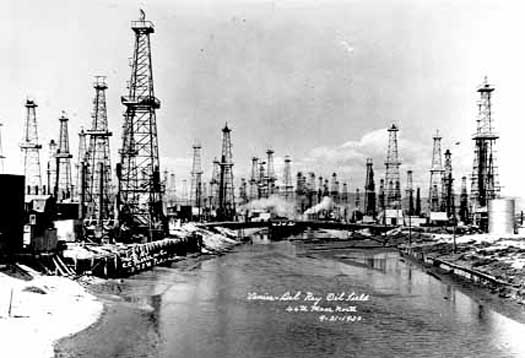

This attitude, combined with strong legal protection of landowners’ rights, has made it more profitable for major producers to ship oil in from the Middle East, leaving the bulk of oil production to smaller companies: “each homeowner could (and sometimes did) start their own company by simply drilling an oil well. As a result over a hundred companies drain oil from underneath the city.” This level of granularity, combined with fluctuating (but generally high) real estate values has caused oil drilling to be perhaps the most ephemeral of LA’s infrastructures, its prevalence totally determined by market forces. Venice Beach might be the apotheosis of this trend. Founded at the beginning of the 20th century as a tourist- and recreation-focused beach town, residents struck oil in 1929. Within two years, the city was completely over-run with wells.

The relationship Los Angeles has with its oil offers an opportunity to reconsider our attitude toward the physical and cultural presence of urban infrastructures — both during their useful life, and after. Ruchala states that “oil is not only hidden in the city’s self-image, its full extent is hidden from sight.” Strongly influenced by the tenets of landscape urbanism, I tend toward advocating for more integration of our infrastructures and public spaces, for more exposure — but this can be highly distasteful to the public. So when does camouflage become the only appropriate tactic for operating in so highly a contested landscape as Los Angeles? I’ll be the first to argue we should be able to come up with better strategies for embedding vital infrastructures within our cities than disguising them as poor approximations of poor architecture, but perhaps the strength of the familiar is a strategy too powerful to be ignored.

A bit earlier in the essay, Ruchala describes this tendency towards hiding infrastructures as not only characteristic of Los Angeles — the Infrastructural City — but of the infrastructural city in general:

If the history of oil — and its disapperance — is unique to Los Angeles, the history of infrastructures vanishing is not. Infrastructural systems once integral to their urban regions and celebrated as beacons of modernity are forgotten as they age and begin to symbolize outmoded economic orders. Los Angeles’s oil infrastructure fits into this historical arc, erased as the region reconfigures itself. But as this essay suggests, this erasure erases Los Angeles as well. Without oil, the region would have turned out to be a far different place.

But why shouldn’t we accept that infrastructures, like ecologies, will shift and vanish? Many of us have a strong cultural (or perhaps philosophical) bias in favor of preservation — of ecosystems, of historic buildings, even, as Ruchala argues, of infrastructures. We argue strenuously about which things are worth preserving, but we argue much less about whether preservation as a default strategy is appropriate. Consequently, we default towards stasis and seek to avoid flux. But just as we’re discovering that this isn’t appropriate ecologically, might it also be inappropriate infrastructurally? Do we need to see the infrastructures of the past in order to remember them? Or, put another way: isn’t discovering that a certain swimming pool was the first oil derrick in Los Angeles more wonderful than turning that derrick into a museum?

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Rob Holmes and dpr-barcelona, Stephen Becker. Stephen Becker said: a day late, hopefully not a dollar short: http://bit.ly/bImOfO about LA's petroleum soaked landscape, chapter 3 of #mammothbook club […]

[…] oildorado · “Ruchala states that ‘oil is not only hidden in the city’s self-image, its full extent is hidden from sight.’ Strongly influenced by the tenets of landscape urbanism, I tend toward advocating for more integration of our infrastructures and public spaces, for more exposure — but this can be highly distasteful to the public. So when does camouflage become the only appropriate tactic for operating in so highly a contested landscape as Los Angeles?”<br /> <br /> Mammoth investigates the architecture of the urban oilfields of LA. […]

your last paragraph brings up an LA-specific question for me. It seems that artifice and fantasy is an important part of LA’s culture (a theme, when combined with suburban sprawl, that you guys touched on in your Volume article regarding the ubiquity and relevance of pastiche in the built environment).

In that case, is it not in keeping or somehow appropriate that these things are covered up by being made generic (like, say a Hollywood movie)?

I’d say that, in a really weird way, yes, it is entirely appropriate. I think that’s what Stephen intended when he said:

I’m not sure exactly what a designer does with that insight, though — not only does it run entirely counter to our common tendency towards “revealing” and “exposing” infrastructures to public use, it then also implies that to attempt to design better camouflage is impossible (because the effectiveness of the camouflage depends on its generic qualities).

If we can’t effectively co-opt this trend, do we oppose it? Do we celebrate it but ignore it, choosing to focus our working energies elsewhere? I’m really unsure. But these are the kinds of questions that we hoped we would start asking by reading the book, so I’m glad they’re coming up.

I love the historic images of Venice Beach. The color one provided in the link is fantastic.

I think we could all chew on that last paragraph for a while. It also seems to sum up a lot of the discussion thus far. I share the opinion that infrastructures have their time and we don’t need to hold onto them. I would further argue that once an infrastructure gets a sizable foothold, or critical mass on a city, it rarely ever vanishes, as each one leaves a traceable imprint and effect on urban space.

I think maybe the really interesting twist in the last paragraph — which is more a set of questions we’re asking than a set of answers we’re advancing — is that it implies that perhaps the prevailing disciplinary response to outmoded infrastructures (Nam helpfully brings up the example of Duisburg Nord, though I think he does so more within the context of the prevailing response — “machines into gardens”, etc.) is a sort of unhelpful infrastructural nostalgia.

That’s largely what avant-garde landscape architecture does with outmoded infrastructures right now — turns them into gardens — so if it really is better to, at least in many cases, accept their ephemeral-ity, then there might be something quite problematic going on in directions the discipline wants to head. Maybe less time should be spent building monuments to past industrial economies, and more time building infrastructures for productive future landscapes that can be the foundation of new economies? (This, coincidentally, ties neatly — at least in my head — into two of my least favorite urbanophile fetishes, the ‘childless city’ (last sentence here, for instance) and the ‘information economy’. I see no future for cities without children and economies without manufacturing.)

this is interesting (as is nam’s post) and brings up another important question for me (one which is summed up nicely in the Dirty Projectors song I quoted on that Terrain Vague post a while back): what is the difference, and the cultural significance, of a monument vs. a grave?

As an aside, something that FAD and Nam have picked up on, is something I have been wondering about for years- what will/can we do with all of the gas stations in 50 years? Will they be hydrogen stations? Covered over with a green carpet/pastiche? Or somehow utilize the fact that massive tanks are below ground, as are petrochemical toxins? Their architecture is distinctive- if banal. Places had a nice photo series on these a few months ago, if I remember correctly.

@Rob and Fasla – the “outmoded infrastructure as garden” approach is one of those things that seems helpful until one confronts the fundamentally toxic nature of oil infrastructure. (This is true of industrial sites more generally.) Without significant remediation efforts, nothing edible will grow there.

There’s no simple way out of this dilemma. If we develop one, I suspect that it will be organic rather than mechanical – bioengineered bacteria that consume oil slicks, for example. More broadly, given the hard limits to rare earth metal extraction that we’re going to come up against in the next few decades, I suspect that the next technological revolution will be in organic machines, or not at all. Here I’m thinking of things like Solray Energy’s use of algae to convert sewage to to biofuels in Christchurch, NZ.

[…] via appropriation, (as myth even) is a softer (or even more durable) approach. Over at Mammoth they suggest that maybe the real lesson of Ruchala’s essay is that instead of tending towards stasis we […]

[…] the “machine as the garden”. A bit of discussion related to that evolution appears in the comments of Stephen’s post […]

[…] you can only think in two things: the old cliche to reference dinosaurs that mammoth mentions at their post or the sense of perpetual […]

Palladium, a company that makes boots (apparently) actually made a video promotion of people visiting unusual locations and landscapes. One of those is LA. There’s nothing really new here, but it does show off some cool places.

The video didn’t embed. Here’s the link.

[…] are constructed from tiny shards of the surrounding mountain ranges, ossified with cement and petroleum. Though concrete and asphalt often seem like infinitely available materials — only becoming […]

CLUI’s exhibit: Urban Crude, which deals with this subject (and owes much to Frank!) is now online at:

http://www.clui.org/ondisplay/urbancrude/online/index.html

[…] has just launched a new online exhibition, “Urban Crude”, which explores the oil fields of the Los Angeles Basin in intimate and fantastic detail. Oil wells sprout like hardy Ailanthus from cracks in big box […]

The questions of concealing, preserving, adapting, replacing, basically living with infrastructure are fascinating to me. I wouldn’t be against concealment if it makes places more appealing (although this is tough to decide objectively, we can at least do better than the Packard site). Preserving certain places that have become beautiful or meaningful is so important. They can still play useful infrastructural roles, or at least not prevent the development of new infrastructure. I hope it won’t be necessary for infrastructure of the future to replace rare and valuable structures from the past. Jukka Jokilehto’s A History of Architectural Conservation has a lot of interesting background on different approaches to preservation. I should revisit that, because many of the ideas seem relevant to ecosystems and human-made infrastructure as well.

“I wouldn’t be against concealment if it makes places more appealing…”

Interestingly, I think it is fair to say that there is a strain in contemporary architecture — call it the landscape urbanist’s equivalent of the modernist’s dogmatic opposition to ornament — which would be ideologically opposed to concealment, but, I think, you’re right and they’re wrong. (Not that I’m never in favor of revealing infrastructures — I’m probably much more often in favor of it than not — but I see no good reason for an ideological presupposition that refuses to consider any case for concealment.)

and be happy with all the other…

areas of my life that are going right and in balance. focus on the positive, eat well, rest well and be at peace with who you are. remember, that for some, hair grows back as mysteriously as it disappeared. female hair…