You’ve arrived at week two of our reading of The Infrastructural City; if you’re not familiar with the series, you can start here and catch up here — taking particular note of the index of contributing posts for the first chapter, which tracks the sprawl of the discussion across other blogs.

[The lower reaches of the Los Angeles River, via google maps]

Like Barry Lehrman’s chapter on Owens Lake, the second chapter of The Infrastructural City, “Flood Control Freakology” deals with a water-bearing infrastructure. Unlike the aqueduct and the damaged playa the aqueduct produced, though, which exist to bring water to the city, this second hydrological infrastructure, the heavily-channelized Los Angeles River, has been re-constructed to remove water from the city. The chapter’s author is David Fletcher, a Californian landscape architect and one of the contributors to the recent Los Angeles River Revitalization Master Plan. Fletcher describes the Los Angeles River not just through the dominant “narrative of loss”, which focuses on the destructive qualities of its transformation from a perennial “meshwork of meandering rivers, streams, arroyos, and washes” to a “fully-engineered flood-control system”, but also as what Fletcher terms a “freakology”, or hybrid system composed of both infrastructural and natural parts, which supports “a vibrant mix of varied ecologies”:

“The present river ecology is a churning soup of exotic and native vegetative communities that have been introduced since the nineteenth century, some by design, others by accident. Tourism, shipping, rail, industry, agriculture, and ornamental vegetation have brought humans, animals, insects, and seeds, from around the globe to colonize the river’s naturalized reaches. These reaches have established a curious equilibrium with their ecologies, depending on nutrient-rich flows from sewage treatment and urban runoff…”

Fletcher’s description of “freakology” continues on for pages, reading like a whirlwind tour of ignored urban landscapes whose conductor is madly in love with what others would see as malignancies and degeneracies: “thousands of multicolored bags — known as ‘Los Angeles moss’ — hang from trees”; human encampments line the concrete channels, “smoke emanating from well-furnished stormdrain apartments”; “thriving parrot colonies” are composed of “ragtag teams of birds that escaped private homes as well as from the old Busch Gardens amusement park, closed in the early 1980s”; “bridges house bat colonies and swallow nests”, which are “critical to urban disease vector control”.

[A point of transition between concrete-bottom (at right) and dirt-bottom (at left), photographed by the awesome FOVICKS, or Friends of Vast Industrial Kafka-esque Sturctures, for a photoessay on the Los Angeles River]

The purpose of this cataloging, though, is not merely to assemble a wunderkammer of landscape curiosities, but also aimed at describing, through the creation of “new narratives and vocabularies”, a more realistic direction for the future of the river. Recent efforts to transform the river are rooted in bucolic aesthetic expectations, demanding a return to — or at least a simulation of — the pre-urban condition of the river, typically understood to mean restored flood plains, daylighted streams, un-channelized river banks, and re-established populations of native flora and fauna. Fletcher suggests, though, that these expectations are not grounded in an honest evaluation of the ecological potential of the system, constrained as it is by the limited quantities of water available to Los Angeles:

“The future of the river and its infrastructural ecologies depends on water availability and flood-control policy. With prolonged drought conditions and growing pressure on water supplies in the American West, Los Angeles will have to become more self-reliant, turning to conservation and greywater reuse as major sources of water savings… As the city grows rapidly over the next decades — primarily through sprawl and infill densification — and as wastewater is re-appropriated for that growth, the city forecasts that the amount of water reaching the river will drastically decrease. Decreased water supplies due to climate change and increasing water demand for recycled water means that soon there will not be enough water to sustain the river’s ecologies and landscapes…”

This stance, and the provocative suggestion that “restoration” is, whether desirable or not, simply not an option, aggressively counters the received orthodoxy in landscape planning, which tends to see distinctions like “soft infrastructure” versus “hard infrastructure” as not only having functional distinctions, but also as existing in a Manichean moral environment: a river bed encased in concrete is always bad, and a naturalized flood plain is always good.

[The Los Angeles River slips under “the” 105, via google maps]

If we can accept for the moment, as Fletcher asks us to, that “freakology” is, at least at times, the unavoidable result of the interaction of infrastructural and natural systems, then we are left with an important and fascinating question: what is a landscape architecture with freakish rather than bucolic characteristics like1?

[Life in the upper concrete reaches of the Los Angeles River, via FOVICKS]

It obviously involves an alteration of aesthetic priorities and models. The bucolic traditions relies most deeply on Arcadian ideals handed down from the classical and Romantic landscapes of Western Europe, peripherally on the garden traditions of East Asia, and more recently upon the elaborate simulation or re-arrangement of previous local ecologies, a la Jens Jensen and Piet Oudolf. A quick browse through the ASLA’s yearly residental award winners evidences the degree to which these traditions have been assimilated into a single bucolic vernacular favored by wealthy clients and their designers. In comparison to these traditions, a gardened infrastructure may be jarring, prone to odd bursts of coloration and seemingly disorganized, but that does not mean that it will not have a beauty — and an organization — of its own. That organization may be more emergent than it is planned, and that beauty as removed from the bucolic tradition as the favela is from Haussmann’s Paris, but that does not mean that we cannot train ourselves to see it.

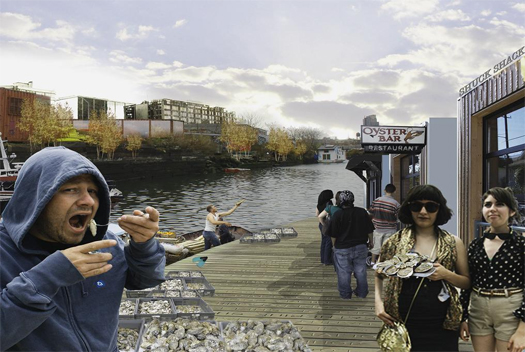

Curating these ecologies may be accomplished less through the traditional tools of landscape design — the bulldozer, the front-end loader, the nursery-grown plant, the concrete pour — and more through the controlled alteration of and experimentation on the processes which input into infrastructural ecologies. This is demonstrated particularly well by two qualities of the SCAPE Studio team’s contribution to the recently opened Rising Currents exhibition at MoMA, “Oyster-tecture”. For that exhibition, each of the five invited teams was given a particular portion of the New York City regional waterfront to respond to. SCAPE’s team was assigned a portion which includes Red Hook, the Buttermilk Channel, and the Gowanus Canal. The Gowanus Canal, which has recently been designated an EPA Superfund site, is an obviously freakish landscape, containing waters so contaminated that their toxicity may actually be of use in researching cancer-resistant and naturally-antibiotic micro-organisms.

[Image from “Oyster-tecture, by SCAPE Studio; via Change Observer]

The first quality of “Oyster-tecture” which seems particularly applicable to designing for “freakologies” is its open-ended-ness. Each of the other four exhibiting teams provides what amounts to a master plan, proscribing particular and desirable potential end states for their sites, though often quite clever in program and form. The SCAPE team, however, proposes to insert a series of programmed architectural objects — an armature for the growth of an oyster-based ecology and economy, whose primary parts are the adoption of the Gowanus canal as an oyster nursery and the provision of a kit of parts on which young spats can grow into a harvest-ready mature reef — into interaction with the existing urban ecologies, both natural and human. While the farming and cultivation of oysters would have a series of anticipated positive effects — biofiltration of contaminated waters, protection against storm surge through accumulation into reefs, cultural and economic revitalization prompted by biological revitalization — and so undoubtedly affect the evolution of both the city and its adjacent waters, the team does not seek to delineate or define exactly what form that evolution will take. This humility (a quality not often ascribed to architectural designers, who have worshipped for decades the cult of the singularly brilliant ego) is entirely appropriate not only for working in the infrastructural city (which, as Varnelis is quick to point out in the introduction, has developed a systemic immune response to the construction of new infrastructures), but also for experimenting with the ecological balance of the “freakologies” our infrastructures have spawned.

[Image from “Oyster-tecture”, via Heroes and Charlatans]

The second quality is captured well by a comment left by Michael Horodniceanu on Mimi Zeiger’s review of Rising Currents for Places:

“SCAPE’s approach to the tide rising is grounded in a sustainable way of adressing environmental changes along New York’s shore line. It allows one to preserve our environment by instituting subtle physical changes along the shore line with the ultimate outcome of reducing the heavy reliance on mega infrastructure investments for protecting our waterfront. While the other solution are imaginative, they rely heavily in a massive infussion of money into infrastructre thus making them less likely to be implemented in the relatively near future. SCAPE provides contemporary, simple yet titilating solutions to protect our environment while pointing towards the implementation of inexpensive and sustainable ways.”

“Oyster-tecture” is, in other words, what FASLANYC has called a “lo-fi landscape”, quickly augmenting an existing ecology at minimal expense, but containing the potentially transformative seeds of a future harbor. Unlike the “mega infrastructure investments” Horodniceanu refers to, which are typically constructed in an interdependent fashion, lo-fi interventions are relatively independent, even potentially experimental in a scientific sense. If we accept that, as Fletcher suggests, the removal of the hard-engineered infrastructural components of “freakologies” is not a reasonable option, then we need effective but flexible ways to hack “freakologies”, and lo-fi interventions offer exactly that.

Finally, objective and scientific measurements, particularly those derived from the field of ecology, are of great utility in approaching “freakologies”, because those instruments can help us shed the cultural baggage which teaches us to consider bucolic qualities indicators of a landscape’s ‘health’ and “freakish” qualities indicators of a diseased state. One useful alternative, drawn from ecology, is the measurement of productivity, which can often occur in surprising places — such as the sewage-rich Lower Los Angeles River. Quoting Fletcher:

“…[running] six miles to the tidal estuary zone, [it] is perhaps one of the most interesting ecologies [along the river]. In this reach, the increased nutrient-rich waters spill out of the low-flow channel, a 1-foot-deep by 20-feet-wide channel running through most of the river. This channel was originally designed to concentrate and conduct silt-laden water out to sea and to allow Steelhead Trout up the river to spawn. But the original design did not anticipate the increased flows from the sewage treatment plants. This effluent-enriched water spreads out across the concrete sills, forming a thriving and vast algal zone, the “Sludge Mat”. Invertebrates have extensively colonized this zone, creating the most biologically productive stopover for migrating shorebirds in Southern California. It has the largest concentration of black-necked stilts in the United States.”

Such assessments, though, must occur at multiple scales simultaneously. It is not enough to know that the “Sludge Mat” is productive and rich, without considering how it affects productivity (and, of course, a host of other measurements, such as diversity) upstream and downstream, and in other ecosystems touched upon by those migrating shorebirds, and so on. This sort of massively interconnected, multi-scalar investigation requires the opposite approach from the lo-fi and experimental models, demanding instead the complex integration and processing of diverse knowledge and data-sets, suggesting that designing for “freakologies” may require a sort of disciplinary bi-polarity, accommodating both radically independent (open-ended, lo-fi) and radically interdependent (ecologically complex, scientifically-tested) working methodologies within the same physical and legal terrain2.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Rob Holmes, dpr-barcelona. dpr-barcelona said: 2nd Week reading The Infrastructural City “the parrot, the weed, and the sludge mat” | http://tinyurl.com/2w6tdmo /at mammoth #mammothbook […]

[…] freakological, at least not in the design or project(ive) sense. The boys at Mammoth in their entry for this week do. They examine the design approaches which could be applied. Or more precisely they […]

I couldn’t agree more with Fletcher about the “narrative of loss” and his focus on historical/cultural narrative is key, in my opinion. I’m working up some thoughts of my own, which you/nam/fad have been informing, and it’s along similar lines. You are right on to make the connection between the freakology and the bukowski-scape, in my opinion.

I really like the leap to Scape’s Oyster-tecture along the lines of eco/cultural narrative, for all the reasons you elaborated on. One of the other important themes there, which Kate emphasized in our interview (though I’m not sure it made the final text) is the historical connection of the project; the project is in some ways a weaving back together of all these narratives that had been frayed by the recent past. In that case, the fact that the Gowanus area used to be famous for its oysters and they used to be a major part of the economy, ecology, and culture was critical inspiration for the proposal. I think that is a key point to add.

Not to stretch metaphors and analogies too thin, but jumping back over flyover country, is there a corollary with LA and the River there???

Gowanus isn’t part of the founding myth of New Amsterdam, while the LA River is part of the myth of Los Angeles. But there are similarities in the loss of public access for much of the length of each waterway and for being ignored for 50 years.

point taken.

but it’s still a part of the historical narrative (according to Kate). And the Gowanus area and its importance stretches back before the revolutionary war.

that historical narrative is not confined to the industrial and post-industrial period.

Maybe the fair thing to say would be that there is certainly an analogy to be made — both the Gowanus and the Los Angeles have mythic dimensions — but that the Los Angeles is more central to the mythology of the city as a whole?

Looking forward to reading the FASLANYC post on this, because I think if there’s any one chapter from the book that is particularly up your alley, this is it.

uh oh.

you had a great point about the “rooted in bucolic aesthetic expectations, demanding a return to — or at least a simulation of — the pre-urban condition of the river, typically understood to mean restored flood plains, daylighted streams, un-channelized river banks, and re-established populations of native flora and fauna.”

actually, one of the things I’m having trouble reconciling is fletcher’s essay and his involvement in the masterplan. i am chalking it up to the fact that a lot more factors/people were involved in making the master plan and that he wasn’t necessarily able to communicate his idea effectively (and this may get back to your point about the term/perspective of freakology).

I think that’s exactly how you reconcile it — I see no reason to think that Fletcher isn’t aware of the conflict between the renderings and his interest in “freakology”, particularly when the plan has fourteen — really, fourteen — teams of primary contributors.

It is probably necessary to have such freakishly large teams to do work on the scale of the entire Los Angeles River watershed, but when your team grows large enough that it could accurately be described as a bureaucracy in and of itself, then it becomes really important that the bureaucracy you create deals with the myriad of public agency-related issues you talked about in your recent series.

My guess, from a superficial reading of the report, is that the Los Angeles River team wasn’t really able to do that, and got bogged down, hence the lowest-common-denominator feel.

I suppose there’s an alternate possibility, too, and that’s that while the plan might be lowest-common-denominator in the ways you identified in your post, it might also be interesting or challenging to the status quo in other places (maybe something related to future water availability, for instance), that don’t necessarily show up in the renderings, but involved pushing hard against bureaucratic inertia? That’s totally baseless speculation, though.

good points, and seeing how good some of the folks on that team are, i am sure they worked to put some teeth into the report, and perhaps the renderings just reflect expectations/preconceptions. that is another strategy, perhaps a good one- push progressive policy while using the renderings as essentially a “marketing” or “visioning” tool to buy some time until policy (new ways of using water, organizing community, etc) can take effect.

Of course, then there is the risk of furthering discontent when things don’t end up looking like a rendering. In all likelihood, the renderings are not that disingenuous, but merely reflect the lcd-effect.

still love the essay though.

[…] home // hide asides // links // index.archive // contact us // about « “the parrot, the weed, and the sludge mat” […]

[…] quote is perfect to go on with the “blogiscussion” around The Infrastructural City orginized by mammoth, that this week is focused on the the […]

Oyster-tecture! I love it!

I love the project. I’ll admit, though, that I rather dislike the name. The constant use of portions of the word “architecture” (and “-scape”) as prefix or suffix for naming architectural projects is kind of a pet peeve. I think it indicates lack of verbal imagination.

second that.

[…] “indigenous” mean in such a thoroughly transformed condition? As Fletcher says in “Flood Control Freakology”: “…the native versus exotic debate is oversimplified: the landscape assemblages should […]

The ecologies that are currently thriving around the LA river reminds me of Mike Davis’ title essay in Dead Cities. A bombed out berlin had fireflowers growing in the ashes, these fireflowers eventually helped to create a new ecology.

I think its silly to think you can go back to some sort of original pure landscape. Its like the asinine arguments of primitivists. That said capital does create toxic environments and its important that we deal with it in some way. The small teams of people going out if not solving the problem, the problem of capital, are at least engaging in interesting experiments.

Theories about the “end of the world” or things like that have been found all over for centuries, though these days the interenet tends to spread them even more. The latest version that has become quite popular is that the world will end on December 21, 2012. Much of this is based on the last date of the Mayan calendar, which is December 21, 2012.Also, the ancient philoshopher Nostradamus predicted disaster around this date as did many cultures also participated in this belief.

[…] But, I would add (and this seems much more important to me): the rise of the performative tree will also be seen in the acceptance and valuation of “crypto-forests”, “cosmopolitan” plant communities, and invasive species. Techentin says: “Wild nature, or what may be left of it, seems all but removed from collective experience.” Despite this collective remove, though, there is wild nature in the city, only it is invasive and post-human, growing in legal and physical spaces of abandonment: a fence on property line, a sliver of land between two properties deemed to have no value as real-estate, the concrete bed of a channelized river. […]

[…] the infrastructural city: a town that excavates itself turning into a series of giant holes, a river that will disappear if its restored to its natural state, the re-watering of a desert lake, and so on. The book’s value in my mind—and what I am […]

[…] ecologies, acknowledging and subsuming lo-fi practices, the D.I.Y. aesthetic, wild urban plants, freakologies, cryptoforestry, ecological performance metrics, labor-intensive restoration practices, gardening, […]

[…] favorite things at the moment, “everyday structures” deals with the quotidian material conditions of landscape, posting both readings from Sanford Kwinter or Henri Lefebvre and snapshots […]

[…] which tilt market dynamics in favor of farming cash crops. Thus Iowa might be said to be an agricultural freakology (the ecoregion it is in is named not for a defining natural feature — like the […]