As I’m gathering projects, proposals, practices, and places to be covered before I wrap up our summer flood-blogging extravaganza (which I expect to do by the end of the month), I thought it worth looking back at a handful of notable posts from mammoth‘s past that concerned flooding. Hopefully some of these, since they are primarily from mammoth‘s first couple months, will be new to readers. In no particular order:

“In 1998, Mexican architect Alberto Kalach and his colleague Teodoro Gonzalez de Leon published La Ciudad y sus Lagos, a bold proposal that examined the potential resurrection ofLake Texcoco, the largest of the lakes which Mexico City’s predecessor Tenochtitilan was founded on. The revitalization of the lake would serve to both benefit Mexico City ecologically and to invigorate the practice of urbanism in Mexico.

The idea behind the Lakes Project descends from a report written by a soils expert and professor, Nabor Carillo, in the 1960s. Carillo held that the centuries of attempts to drain the lakes of Mexico City (intiated by the Spaniards shortly after conquering Tenochtitilan) were in error. Those centuries of efforts — perhaps most impressively represented by the 1789 completion of the Nochistongo ravine and the networks of canals such as Huehuetoca — had left Mexico City lying below the phreatic level (the natural surface of the static water table) and consequently in constant state of war with floodwaters. Carillo’s program was radical because, rather than continuing and expanding efforts to funnel water away from the city, he suggested ‘reconstructing the city’s original lakes as natural detention ponds for controlled flooding and containment of treated wastewater’.”

“Louisiana senator Mary Landrieu, returning from a tour of the Netherlands’ coastal armaments, says America needs to “rethink its entire approach to low-lying coastal areas and adopt an integrated model of water management like that of the Netherlands”…

Landrieu explains that the Dutch system is superior both in its integration into the landscape — as mentioned above, parks and open spaces serve as flood reservoirs, while the more modern portions of the Dykeworks are designed to allow the mixing of fresh and salt water that sustains fragile estuary habitat — and sheer weight of structure dedicated to firming the line between sea and land. Perhaps this seems slightly paradoxical, as this implies at once acknowledgement of the necessity of accepting the ambiguity of the relationship between land and water at the coast (which is not so much a line as an average drawn from unstable data points) and a far more serious effort at crystallizing that line through the construction of megastructures. But the flexibility to hold these two contradictory stances in tension maybe exactly the flexiblity that the Army Corps of Engineers needs to develop. The Dutch example may even suggest that an architecture of flexible insertions that reprogram the radical flux of natural systems and an architecture of mammoth bulwarks against that radical flux are not wholly incompatible.”

3. its prettiness and romance will then be gone

“As long as I’m on the subject of urban parks that serve as components of flood management systems, I ought to mention the recent Buffalo Bayou Promenade in Houston, which is not only an admirable and forward-thinking project from a city not known for its innovative ecological design (though they have built a rather seductive tangle of on and off ramps), but also manages to mash three of my favorite things — urban parks, flood control and freeway interchanges —into the same space.”

4. the new dutch water defense line

“The original Dutch Water Line (whose function and mechanism can be easily dervied from the variables in the English translation, “inundation line” and “water defense line”) dates to 1629, when Prince Frederick Henry, inspired by the successful use of flooding as a defense mechanism during the Dutch War of Independence, began to execute a plan to construct a “line of flooded land protected by fortresses”.

This national defense system of weaponized artificial hydrology proved remarkably successful during the 17th century, halting Louis XIV’s invasion of the Netherlands, but less so in the 18th, when the French took advantage of winter ice to bypass the Water Line.

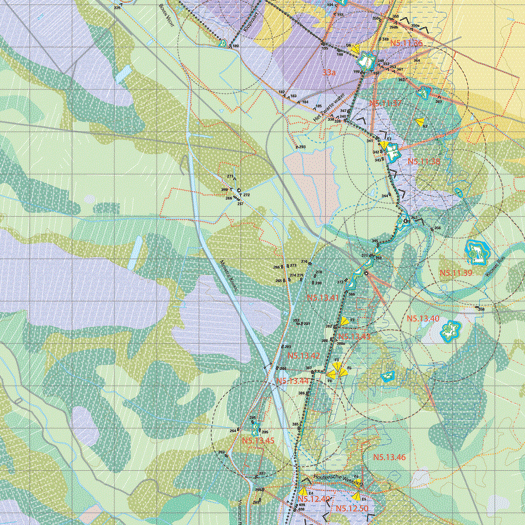

The idea of weaponized hydrology was firmly ensconced in the national consciousness, though, and, after the formation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in the early 19th century solidified national borders, the Nieuwe Hollandsche Waterlinie was constructed to the east of the original Waterlinie. Between three and five kilometers wide, the zone of potential inundationstretched “approximately 70 kilometres from Muiden (situated on the Zuiderzee, currentlyYsselmeer), past the city of Utrecht towards the east, down to the large river district (the Nieuwe Merwede) and the Biesbosch,” at a depth of 35 to 50 centimeters (just deep enough to prevent crossing with artillery, but not deep enough for boats) — approximately one hundred and seventeen thousand cubic meters of ominously empty space, imbued with military potential.”

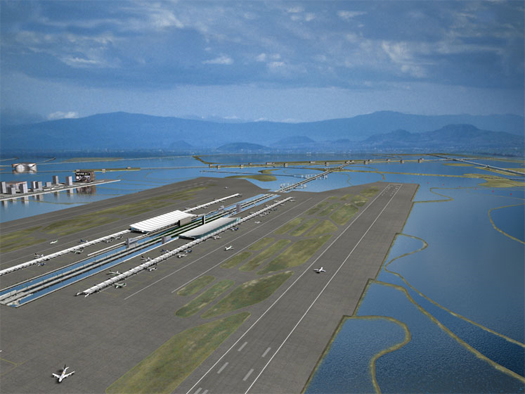

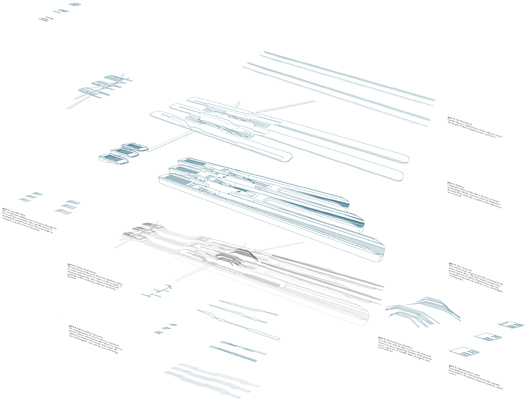

“‘Staging Ground’ is the thesis project of recent Harvard GSD graduate Andrew tenBrink. In it, tenBrink explores a series of topics which make frequent appearances at mammoth: delta urbanism (in this case, the inverted Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta of central California), climate defense systems (here, levees, polders, dikes, and weirs), post-natural ecologies, and, perhaps most pertinently, what tenBrink calls ‘the agency of infrastructure’.”

[Full image credits can be found in each of the referenced posts.]