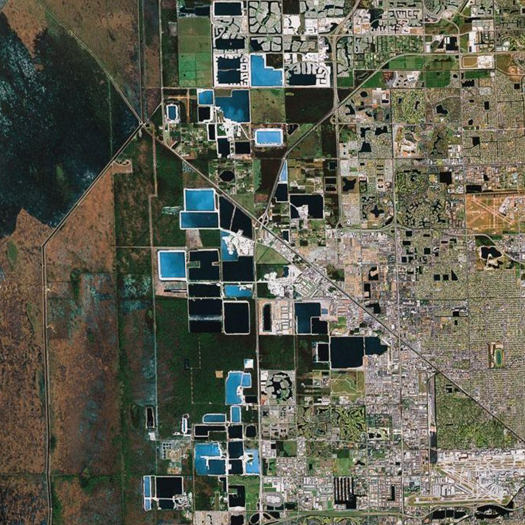

[Miami’s Lake Belt, the zone in which the city of Miami becomes a mirror image of itself — reflected in blue polygons induced by the mining of the limestone rock literally used to construct the city — before it disintegrates into the Everglades.]

I’ve gotten part way through listening to the portions of last weekend’s Landscape Infrastructures symposium that have been posted online, and was particularly struck by comments that Charles Waldheim made in the closing roundtable:

“I was struck by Neil Brenner moderating the second panel [as he] brought it to a close by saying something to the effect of “the idea, the model, that somehow our action around urbanism should concentrate in the cities, is an outdated notion”.

That struck me as correct, and, at the same moment, if that’s true, it has enormous implications for those of us in [the GSD] and in these disciplines. If in fact we should focus on urbanism and urbanization and its infrastructure, not necessarily focused on the city and an opposition between the city and the externality of biological process, it strikes me that there’s an equally profound paradigm shift potentially for us in landscape architecture. I think, you know, for the better part of the last half-century, in our field, we’ve been operating under a paradigm in which nature exists outside of human agency, the kind of classical if not modernist defintion of ecology, in which urbanization was the problem. And having said that, what I’ve heard over the course of the last twenty-four hours, is that we need to fundamentally re-think that paradigm. [In terms of] the practices that we engage in, the models and habits of thought, the tools, the representational tools that we have available, to be able to think through our commitments, both to social and cultural production, but equally to environment and ecology, absent the idea of our extraction from those natural systems.”

This seems a profoundly important point for landscape architecture, in particular: that urban and natural systems are inextricable, not opposed. Indeed, that they have always been, though the scale of that intertwinment is rapidly accelerating. (If that inextricability seems obvious, it is also important to recognize that an understanding in which natural and urban systems are not just in conflict but fundamentally exclusive has been, as Waldheim notes, the primary paradigm within environmental land planning for at least a half-century.)

One consequence of this is that density and urbanism should not be conflated as if they were always one and the same thing. Density, rather than being the primary characteristic that determines whether a place counts as urban or not (a definition which produces endless pointless arguments about exactly how dense a place must be to be urban), is merely one of the important effects of processes of urbanization. It is a peculiarly important effect in any number of ways — economically, ecologically, phenomenologically — but it should not be mistaken for an essential characteristic of urban terrain.

This is supported (as we’ve noted before, after Christopher Grey) by the definition that Ildefons Cerdà provided for urbanism when he coined the term: “the science of human settlements at various scales and times, including countryside networks”. It’s not terribly far from “countryside networks” to “landscape infrastructures”, is it?

Another really interesting thing, related to both Waldheim’s point and the de-conflation of density and urbanism, is what this indicates about where opportunity lies for landscape architecture as a discipline. While much progress has been made by firms like MVVA and Field Operations in finding roles (leading roles, even) for landscape architects on projects within the envelope of density, it seems to me that the more stretched the scale of an urban network becomes, the more it becomes uniquely suited to design by landscape architects. Put concretely, there are vastly more square miles of land in, say, the artificial watershed of Los Angeles than there is spare open land in Boston’s city limits; and what other design discipline is used to working with so much land? An expanded definition of urbanism quite literally has more room for landscape architecture.

I think it strange that this idea wasn’t a part of their thinking before, and actually remembering some of the projects and people that have come out of the GSD in the last decade, this quote from Waldheim strikes me as anachronistic… One would think they aren’t allowed to read Nature’s Metropolis or Steamboats on Western Rivers up there or something…

Nonetheless, I love the admonition that landscape architects move out of the city while remaining in the urban. This is something you and FAD (with his “Corporate Ecologies” work) have been actively doing for a bit now, and one reason that I think the Conservation Ag studio at Nelson Byrd Woltz is so interesting. It’s amazing the amount of work landscape architects have wrung out of the construction of just a few landscape types (park, street, playground, plaza).

But a question- you mention that landscape architects are adept and used to working at scales as large as the modern LA watershed (I believe you put it much more viscerally- “dealing with that much land”- wich I love). Are there specific conceptual tools, techniques, ideas, histories that we seem to generally bring that architects, planners, geographers, or civil engineers might not?

“this quote from Waldheim strikes me as anachronistic”

I think you often find that with Waldheim, but I also think it is deliberate on his part — as he has transitioned into the role of public spokesman for landscape urbanism (and, to some degree, as head of GSD Landscape, for the direction the discipline of landscape architecture as a whole is moving, insofar as it has any corporate vector), he tends to speak in a way that addresses a more general public, both within the discipline and without. Which seems fine, good, and useful to me — this understanding of “urbanism” may have existed for some time in the academy, but it has hardly penetrated popular consciousness (even, I think, within the discipline).

“specific conceptual tools, techniques, ideas, histories that we seem to generally bring”

This is a great, great question, and key to the whole project of designing urbanism at broader scales.

Histories, I have thoughts on, but for another time…

Techniques, the first that comes to mind is “mapping”, which I would say is a set of drawing techniques that differs, both as a mode of representation and as a mode of thought, from “architectural drawing”. (Landscape architects engage in both, of course.) I’m not sure that “mapping” is exactly the right word, because the kind of drawing I’m thinking of is somewhat different from the simple process of “map making”. Maybe there is a continuum from “map making” to “architectural drawing” and “mapping” lies somewhere in between, as a kind of drawing that is more concerned with reading, site, process, generative conditions and externalities than “architectural drawing”, but more intimately linked to the design process and the interfaces between intentionality, agency, and matter than “map making”? Thinking out loud here…

The relationship between density and urbanism were also teased out recently I think by two related(ish) news topics.

Newly released

http://www.scpr.org/news/2012/03/26/31795/census-l-nations-densest-area-passing-nyc/

numbers from the Census Bureau say Angelenos are living in the nation’s most densely-populated urban area. New York still has the highest population, but at 7,000 people per square mile, the Los Angeles/Anaheim/Long Beach area takes the density prize. In light of these new numbers it was I though enlightening to also read about how a some Angelenos are resisting efforts to rezone and allow/encourage TOD and higher density within the city limits.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/29/us/far-reaching-rezoning-plan-for-hollywood-gains-key-support.html

They assumption being that a switch to tall towers, in effect making LA more “urban” in form would ruin the character of their neighborhoods and would be a boon to real estate developers rather than locals.

Too faslanyc’s post I would also totally agree re: the strawman of shorts Waldheim is putting up since he is speaking, although maybe at an academic conference, I think more to the public, non specialist, or even to other professionals but not design/theory academics, perhaps (ie: engineers or other sorts of infrastructural shapers)?

Nam,

Alissa Walker posted an interesting comment on that Times article. (Not that I’m taking sides here — just thought it was an interesting counterpoint.)

The density of Los Angeles is an interesting thing — one of the first things that impressed me about it flying into LAX. A different kind of density — flatter, maybe, with less peaks and valleys? — but even the areas of pure single-family homes on individual lots have a real density to them.

@Rob the irony in that post is awesome… and a valuable counterpoint i would think. Yet, i think the small-mid size towers she shows are I think as much as half a short as the new proposed reqs.