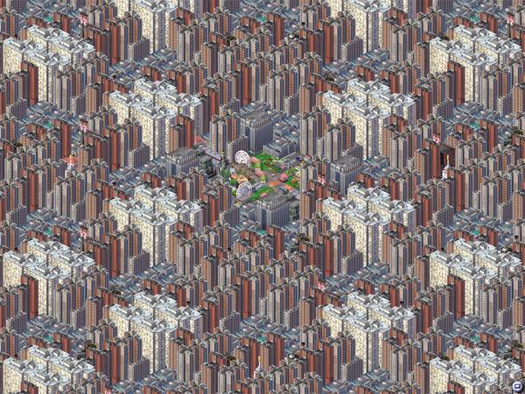

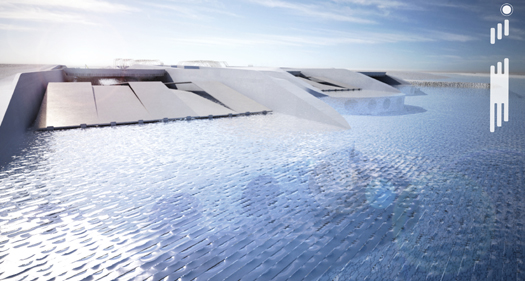

[“Weather Field”; Lateral Office + Paisajes Emergentes for Land Art Generator Initiative]

As we have nearly reached the conclusion of our collaborative reading of The Infrastructural City, we thought it would be interesting to discuss some of the lessons of the text with one of mammoth‘s favorite architectural studios, the Toronto-based Lateral Office. In a series of emails, mammoth spoke with Lateral’s Lola Sheppard and Mason White about why the Economist is more essential reading for architects than Wallpaper, what an “expanded field” for architecture might look like, how to evaluate the performance of a speculative proposal, and, of course, The Infrastructural City.

Readers of mammoth are likely also familiar with Lola and Mason as two of the founders of research-group-slash-blog InfraNet Lab; in addition to Lateral and InfraNet, Lola teaches at the University of Waterloo and Mason at the University of Toronto. The awards that Lateral have received include Canada’s Professional Prix de Rome in Architecture, selection for Pamphlet Architecture 30, finalists in the WPA 2.0 competition, the Young Architects Award from the Architecture League of New York, and the Lefevre Fellowship for Emerging Practitioners from Ohio State University.

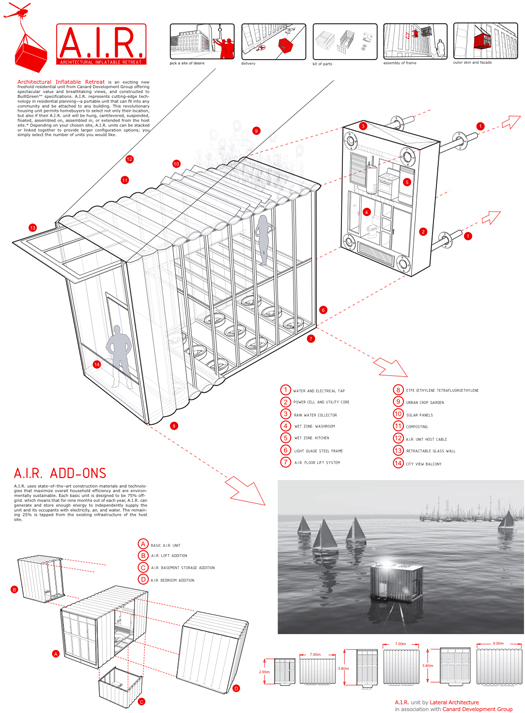

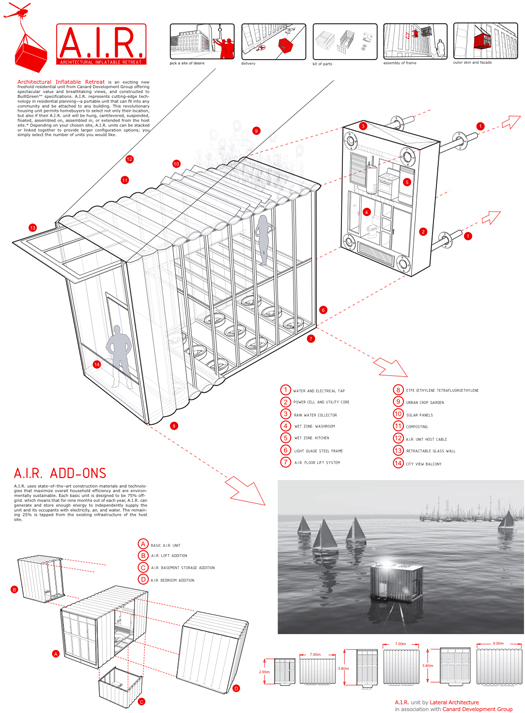

[A.I.R. Unit; Lateral Office with artist Sara Graham]

mammoth: The reason that we thought an interview with Lateral might be particularly appropriate at this time is the overlap between the text that we’ve been reading and discussing this summer — The Infrastructural City — and your work, which has largely been about imagining new typologies for and relationships to infrastructures. Even those projects, like the A.I.R. Unit, which concern more traditional architectural programs like spaces for dwelling show a clearly infrastructural way of thinking about architecture. How did you become interested in infrastructure?

Sheppard: I’m not sure that, initially, we would have identified our work specifically as being about infrastructure as a category. But we would say that we began, even when dealing with single building or public space, with a desire to unpack the systems which underlie a given site or condition. I’d say we were more interested in format than form. There were two early projects which probably changed the way we thought. One was a competition for a dock in Memphis, TN, where we looked at harnessing changing water levels and seasonal flooding to drive the project — and produce sounds. And the second was a research project from 2003, entitled “Flatspace”, which we pursued as Lefevre Fellows at Ohio State University. We were researching the reformatting of expansive retail corridors and ended up generating nine proposals, three driven by program, three by landscape and three by mobility networks. That project sowed the seeds for the strategies and approaches in our later work.

I think also that we have always been interested in rethinking the overlooked parts of our built environment — and much of what organizes these environments seems to fall under the category of logistics and infrastructure.

White: Those early projects, though naive and more searching than strategic, were foundational to our approach to current work. And I really only wanted to add that, regardless of the term infrastructure, we are seeking the limits of an extrinsic architecture, and this often circumstantially addresses infrastructure(s).

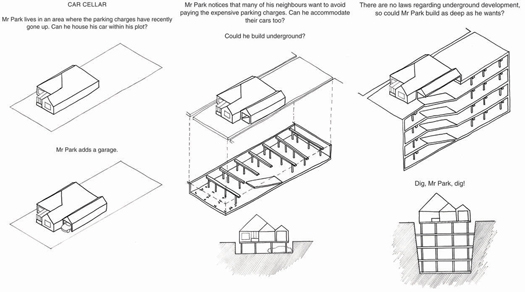

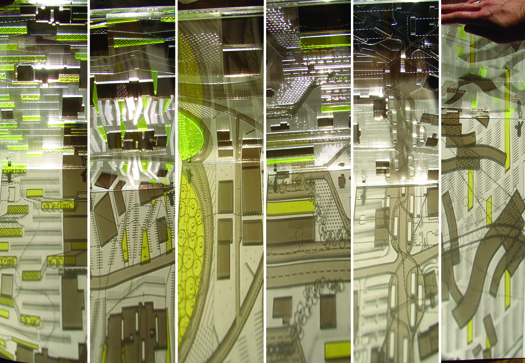

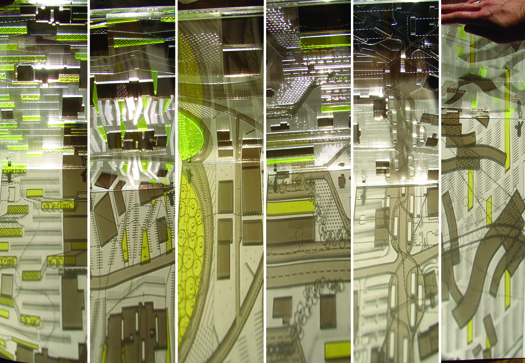

[Models from Flatspace; Lateral Office]

mammoth: We’re glad you brought up “Flatspace”, as it has been on our minds this week — the chapter of The Infrastructural City we read this week deals with the same exurban landscapes of distribution and consumption as “Flatspace”. (It also happens to be how we first learned of Lateral, after it was published in 30 60 90.) We’ll return to it shortly.

But, first: what is ‘an extrinsic architecture’?

White: This is something we are asking ourselves as well. We are finding it to be an architecture that is very aware of its external influence, and maybe more importantly, any opportunities afforded by that awareness. Really, with our work we are seeking an understanding and incorporation of the ever-ricocheting effects and potentials of a work of architecture. Asking ourselves: how deep into its region or environment does a project reach? And quite often, this has taken us out of architecture, and into economics, ecology, energy, and others.

mammoth: An interesting question this raises is the issue of expertise: obviously, as architects, we are not specialists in economics, ecology, energy, and so on. What about being an architect enables us to make useful decisions about the interactions between architecture and these other fields? More specifically, how has Lateral approached investigation into territories — like, say, the logistics of big-box operations you investigated in Flatspace — where you do not have specific expertise?

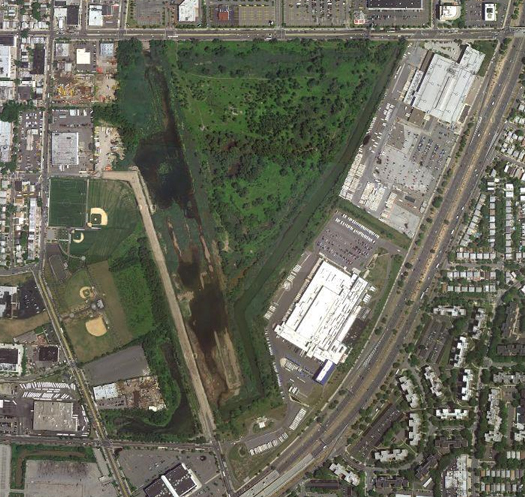

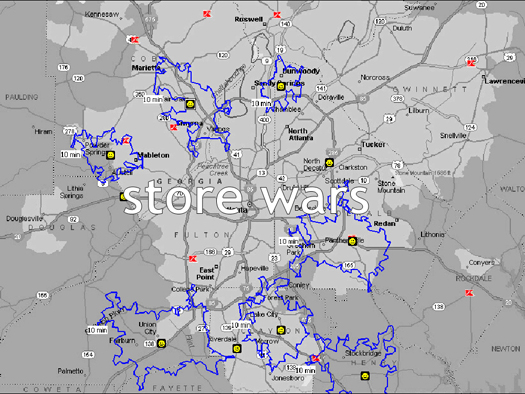

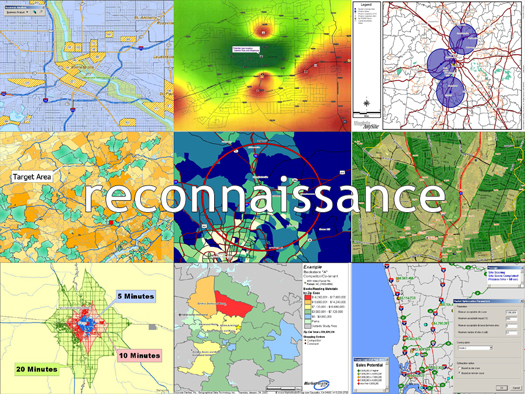

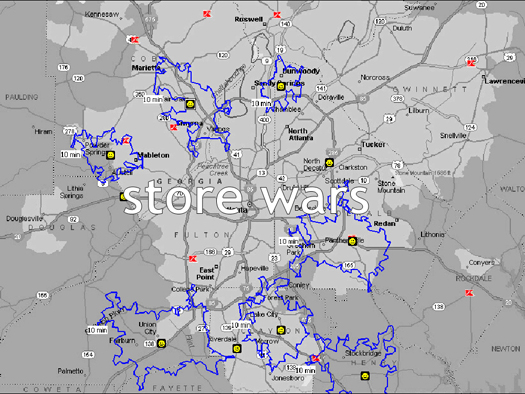

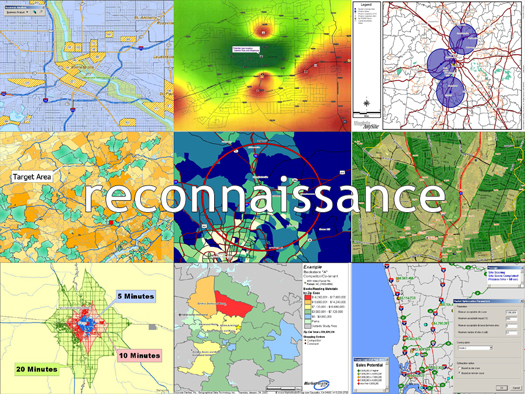

Sheppard: It’s a good question, and one I’d say we grapple with often. We increasingly begin projects with broad and open initial research, to get a sense of the range of issues. For instance in the Flatspace research, we looked at a whole host of issues – the role of GIS, aerial photography, site targeting and the entire militarization of site identification, the notion of ‘branding the land’, the role of zoning regulations, the construction of big boxes…

In this scenario, armed with at least initial knowledge, I think the role of the architect is to read the opportunities. Specialist will have deeper but narrower readings of a specific site or context. As in tunnel vision – it can be sharp but narrow, potentially overlooking issues that aren’t categorizable. I think we try to have 270 degree vision. The architect in this scenario is not simply problem solver, but cultural, environmental and spatial detective, bringing to light the forces (geographic, economic, and cultural) at work within a given geography, and able to look for synergies between issues and opportunities.

[Flatspace; Lateral Office; “the expanded field of retail corridors“]

White: The specialization issue is a prickly one – but I think worthwhile to expand upon a bit. And here I am always reminded of the fox versus hedgehog debate that Isaiah Berlin illuminated. (The fox being an expert generalist, and the hedgehog being an expert specialist.) I think this debate is also one that made us more sheepish about our work in the beginning – thinking that it was not a methodology we should be pursuing for the very reasons you just mentioned, and that we should specialize in something overtly architectural–forms, materials, fabrication. But over time, our position has solidified more as a specialization on phenomenon and opportunities that is between categories and disciplines. For example, I still think the most important magazine to subscribe to as an architect is the Economist, not Wallpaper. Reading the Economist as an architect, you can see things before they become relevant in architecture, with Wallpaper or Dwell you are seeing it after the fact, as a trend.

Really we are most interested in questions of architectural typology and spatial format, and these are often promiscuous interrogations.

mammoth: It’s interesting that you say that, at the outset of your work, you thought you “should specialize in something overtly architectural”, but you’ve since been pulled towards more “promiscuous” work. Was there a particular moment — or project, or set of projects — that produced this shift?

White: It is hard to say that there was a specific moment, but probably some combination of the Flatspace research project at Ohio State University as Lefevre Fellows and a general skepticism of our own professional experiences, as well as the education that brought us to that. More optimistically, it was likely a reaction to a broader position and potential for architecture that lay latent in early work and approaches as students. But, probably hard to identify a particular moment. From early on, we were very influenced by the work and thinking of Keller Easterling, Bucky Fuller, Cedric Price, Constantinos Doxiadis, and others, such as Georges Perec, Paul Virilio, and Luis Fernández-Galiano.

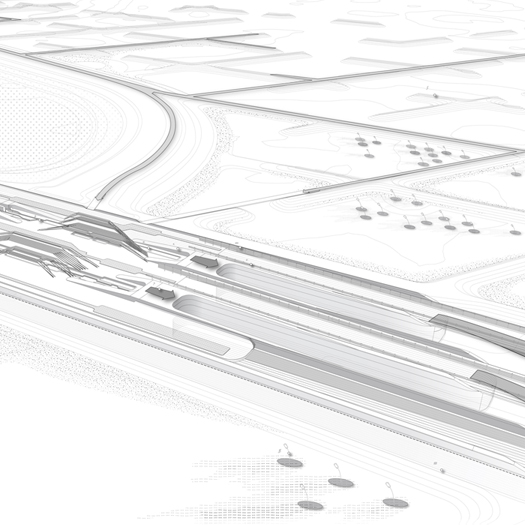

[Farming Salton; Lateral Office for cityLAB’s WPA2.0 competition.]

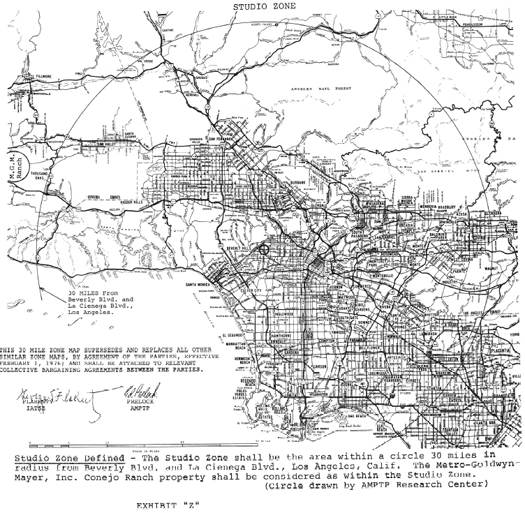

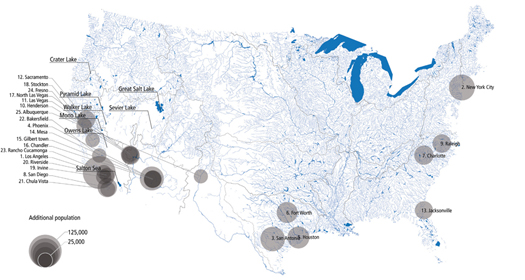

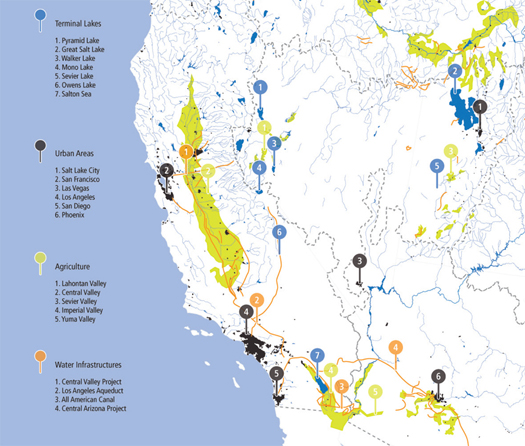

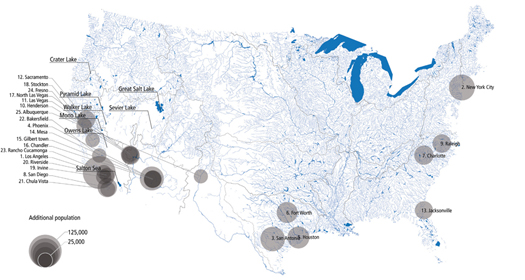

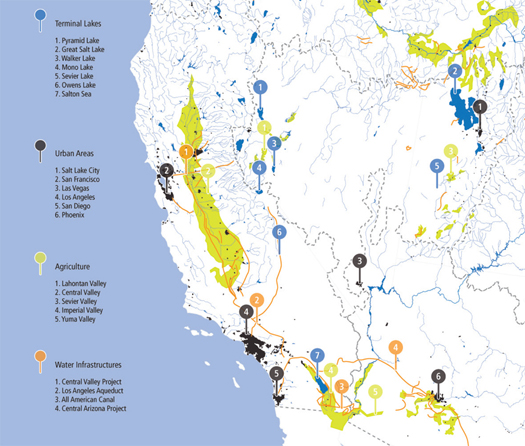

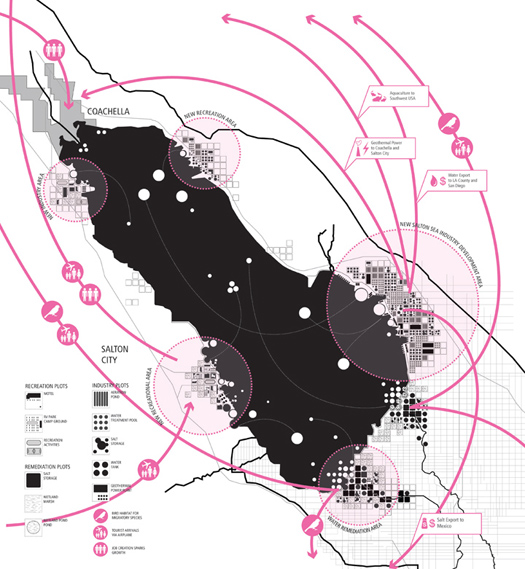

mammoth: The very first chapter in The Infrastructural City, Barry Lehrman’s “Reconstructing the Void”, is about Owens Lake, which is an extraordinary post-infrastructural, post-natural landscape north-east of Los Angeles. South-east of Los Angeles, of course, there is a larger and more famous, but similarly post-natural body of water, the Salton Sea. Your entry to the 2009 WPA2.0 competition, “Farming Salton,” takes the devastated condition of the Salton Sea as an opportunity, proposing a series of new infrastructures to be overlaid onto the Salton Sea and surrounds, with the aim of generating new sustainable ecologies, new economic generators, and new recreational opportunities.

One of the things that you suggest in the project is that these new infrastructures should be “coupled” — that “multiple processes [should be bundled] with spatial experiences”. (Given that “Coupling” is also the title of PA30, it seems fair to say that this is a common theme in your projects.) Why is this important?

Sheppard: We’ve been huge fans of The Infrastructural City because it has served as an original medium for outlining the scope and potential of readings of infrastructure.

The question of ‘coupling’ is interesting to us, because if you look at the history of most infrastructure, it has tended to be mono-functional. It typically consists of engineering projects designed to address a single problem. We’ve recently been talking about “landscapes on life-support,” where infrastructure, in the current condition, serves to simply maintain a failing ecological state. (Owens Lake is such an example, where the state of California spends upward of $415 million on the Dust Mitigation Project simply to prevent toxic dust from spreading.) In projects such as Salton or Icelink, we ask: can infrastructure be more pro-active or more catalytic? Can it serve to support other conditions — ecologies, economies, and public realms?

Our interest in infrastructure really began with an interest in expanding the scope and territory of architecture’s realm beyond the singular building, to include more mutable or contingent conditions. We wanted to embrace questions of economy, logistics, ecology, etc. Infrastructure emerged as a basic precondition for all these questions. Alone, it remains a purely logistical operation. However, in coupling or bundling multiple functions that operate like epiphytes, an expanded territory of intervention emerges. An architecture which responds to opportunities of contingency manifests itself in atypical spatial formats. In a sense, what we’re exploring are these new formats for architecture ‘in an expanded field’.

(We are hosting a topic session at the 99th ACSA Annual Conference next March in Montreal, entitled Architecture’s Expanded Territories, on many of these questions.)

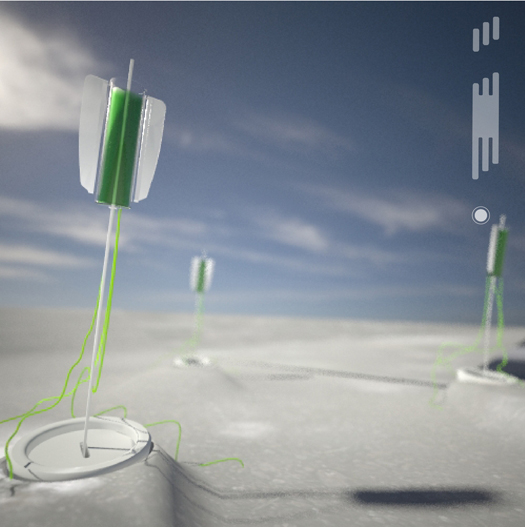

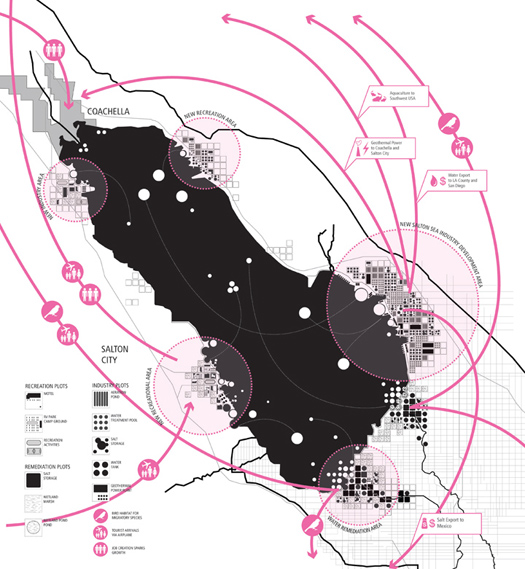

[Icelink; Lateral Office]

mammoth: One theme that recurs frequently in The Infrastructural City is a certain pessimism about new infrastructures on the scale of California’s aqueducts or Los Angeles’ freeways. The primary factors that are pinpointed in being responsible for this are not a lack of architectural interest but deep structural issues: both economic — the current global malaise — and political — a combination of NIMBYism with legal gridlock. This might be described, broadly, as a crisis of “traditional infrastructure”.

Do you share this skepticism about the future of traditional infrastructures in North America? It seems to us that some of your recent work — thinking in particular of Farming Salton, but perhaps also the Emergent North research — could be partially construed (though you may disagree) as a response to this problem, in so far as it is an attempt to describe alternatives to “traditional infrastructure”, where infrastructure might retain its capacity to generate and guide the growth of human settlement patterns, but also become more flexible, more distributed, less mono-functional.

White: We certainly share that pessimism, and much of this came up in a panel session with Kazys earlier this summer as part of the series of discussions on “networked publics.” The discussion led to several questions that we are often preoccupied with: what scale(s) does infrastructure operate at, what does infrastructure respond to, and what form might it take? And we are quite partial to the position of infrastructure as soft, scalable, and market-responsive. And, yes, that is a critique of “traditional infrastructure,” which is hard, big, and a product of its market-time.

Infrastructure should also be entrepreneurial — something that both the Salton Sea project demonstrates and our ongoing work in the Canadian Arctic will seek. The combination of public and private investment is an emerging market (of which the PPIAF is an interesting real-world precedent). But we also share a degree of skepticism about infrastructure as a catch-all realm of practice. The term has increasingly expanded to stand-in for any architecture serving as a process or a system — and this mirrors the post-economic collapse return to function after the heady days of exuberant cultural projects. The attention that infrastructure is getting is further evidence of a shift to processes over objects. Though maybe what we are seeing and how we are positioning our work, is not an abandonment of architecture or a naive fascination with infrastructure so much as a renewed interest in an emergent territory of practice that is between these. We are finding that many of the questions that architecture could be asking are being picked up by others. Architecture is slow.

Through the research at InfraNet Lab, with colleagues Maya Przybylski and Neeraj Bhatia, we are trying to position and qualify our understanding and forecasting of architecture’s potential as influenced by and integrated with infrastructure. Maya brings an interest in computational infrastructure, and Neeraj an interest in social infrastructure. The Lab gives us a space to intersect these interests. Much of this position will be evident in Pamphlet Architecture #30 and the first issue of our collaborative journal with Archinect called Bracket.

We were asked recently if we were a “trans-disciplinary practice,” and although it would be convenient to say yes–and likely with much evidence in the work–I think our preferred answer is that we are anti-disciplinary … or maybe un-disciplinary. The only time I would say being undisciplined is intentional and productive.

mammoth: This contention that “infrastructure should be entrepreneurial” is intriguing — both in and of itself, and also because arguments for a renewed commitment to infrastructure (whether general, like Krugman’s recent op-ed in the New York Times, or specifically architectural, like Nancy Levinson’s editorial piece for Places) so often are explicitly arguments for public work over and against private work.

That said, it’s an assertion that we are broadly in agreement with.

Part of the in-and-of-itself interest is that ‘entrepreneurial’ implies an evaluation of performance — process, not just object, as you noted. This is true of much infrastructural design generally: you need to be able to simulate performance (of economies, or hydrologies, or traffic flows, or structure), and simulating performance is a much bigger component of the design process that it would be for a more ‘typical’ architectural project (like a house).

So maybe the interesting question that arises then is — particularly in a research-oriented context like your work on Salton or the Canadian Arctic — how do we test the validity of the entrepreneurial qualities of our proposals? Do you have a particular example of how the development of entrepreneurial qualities (or some other objective tangentially related to a project’s explicit function or performance) fed back into the design process as a whole in a given project?

Sheppard: It’s interesting — this question of how does one evaluate performance. In most cases the economic and ecologic proposals we are leveraging are common, even proven models, such as job creation or remediation. Maybe what makes them unique for us is that they can be positioned in tandem rather than as oppositions.

Large infrastructure projects, such as those of the WPA 1.0, created jobs during their construction that ceased once the projects were built. (Although one could argue that long-term benefits were skills training, and the creation of large arts and literacy projects.) The TVA (Tennessee Valley Authority) is perhaps the more interesting model. It too was a major employer during the depression, on the construction phase of projects. However, it continues its relevance today through economic development, job creation, education, and research. Rather than simply providing an energy resource, its role is more diverse, tentacular and long-term.

In the example of the Salton Sea, there are existing (engineered) proposals that are coming with price tags of over $8.9 billion, with an additional $140 million each year. And this is largely to maintain a status quo, and prevent further decline. Something is going to be built there, and the question is what does the public get in return for that bill? In our proposal for a project that could be built incrementally, the intention is to engage a different thinking about investment. But more importantly, the project seeks to generate ongoing economic benefits, through new industries that might dovetail into the infrastructure, and through restored ecologies that in turn reinvigorate recreation and tourism (once the lifeblood of the region). The intention is that entrepreneurial economic returns have a much longer life.

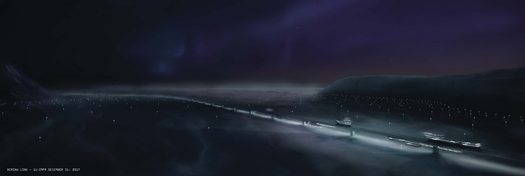

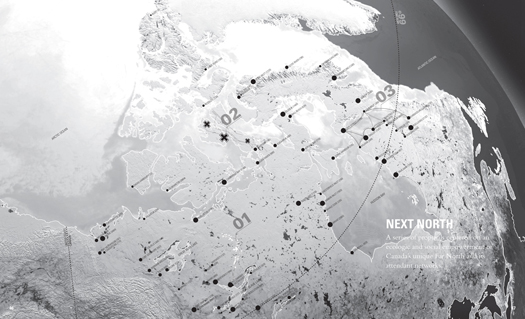

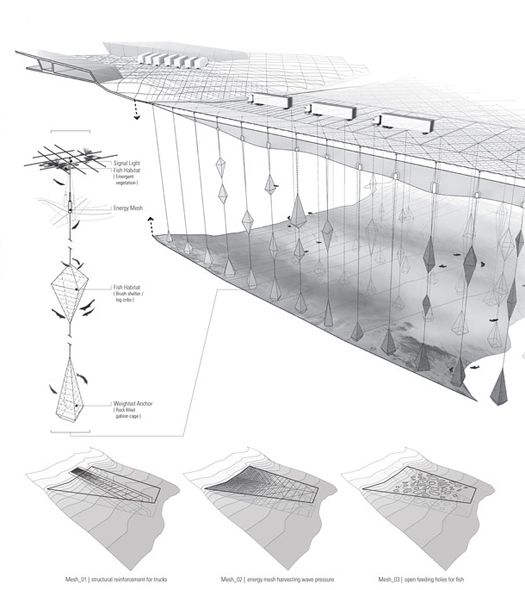

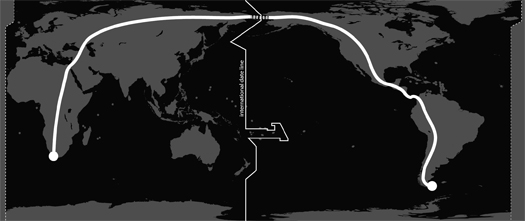

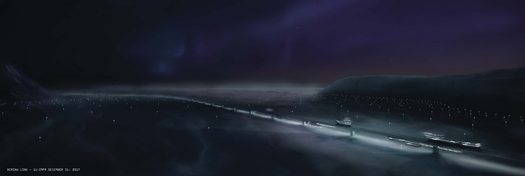

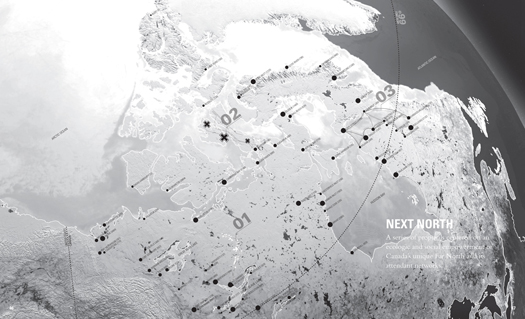

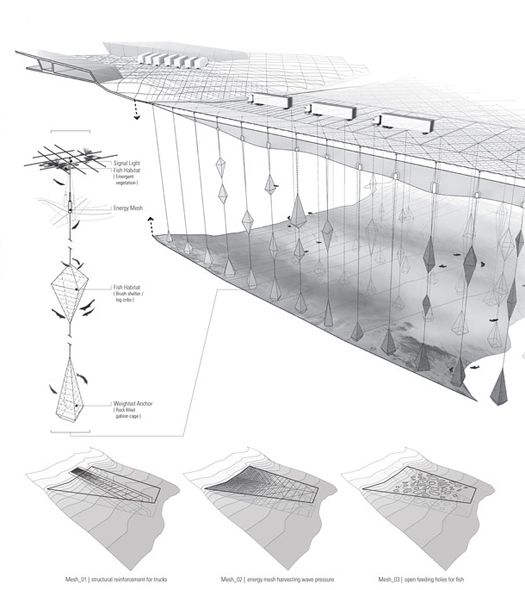

In a project such as the augmented Ice Roads (near Yellowknife, Canada), our criticism is that the engineered ice roads have a short operational season and serve one use for an average of 67 days a year. We’re asking how can one extend the operating season, stimulate the ecology (through fish hatcheries), and aggregate other programs — in this case recreational fishing and adventure camping — to generate increased returns.

In all these projects, the underlying question is how might design address the integration of these various operations.

[Project map (top) and augmented ice roads (bottom), from Emergent North; Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab]

mammoth: We very much like this idea, that explicitly describing the various tangential economic benefits of a proposed infrastructure becomes a part of the design itself — rather than, as is probably too often the case, being seen as something that is extrinsic to the work of design. A close parallel to this might be the research of Roger Sherman, whose chapter in The Infrastructural City (“Count(ing) on Change”) seeks to demonstrate that the negotiations required for the implementation of a project not only do not necessarily detract from the project, but can often be a productive enterprise leading to otherwise unforeseeable solutions. In both cases — you, integrating and aggregating programs, particularly economic; Roger Sherman, exploring the possibilities produced by processes of negotiation — something which is often thought of as prior to and even antagonistic towards the process of design is wrapped into design, enriching it.

In a recent interview at Places, the landscape architects Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha were asked to describe their model of practice, which they have referred to as “activist practice”. For them, this means that, rather than pursuing clients and commissions, they have sought to do projects — often taking the form of publications and exhibitions — which question cultural understandings of landscape, which provoke questions. They break “conceptual ground”, rather than physical ground. This idea — that practicing landscape architecture or architecture means much more than just building buildings or planting landscapes, as obviously important as those things are — is not new, but it does often seem to be perennially lost in the distinction that is made between “real” and “paper” architecture.

One kind of “conceptual ground” that Lateral is explicitly engaged in breaking is this work of developing an “expanded field” for architecture, which would obviously include the sort of additions to the process of design that we’ve been discussing. But, more broadly — yet thinking specifically of things architects do — what does “practicing architecture” mean to Lateral? Since we’ve already been dancing around this question (and phrased that way, it’s perhaps a bit broad), perhaps one way to think about this might be to tell us about what you think or hope the future might hold for Lateral.

White: We are not very good at forecasting in the mirror, but I can say that the combination of writing, research and design has helped to chart our thinking within the field. As for how this might define a practice, we are willing to let this take place naturally as and when opportunities arise. But I think we are ultimately interested in reformatting an architectural practice – we aspire to the design of ideas and idea of design, though we don’t think this precludes building. However, we have turned down the model of a boutique practice in order to pursue projects in the public realm from the outset, rather than ‘graduate’ into that kind of work.

As for your comment on the expanded field, architecture will continue to oscillate between bouts of autonomy and transdiciplinarity for some time. This has been evident in the last decade or so, and we have made our allegiances to transdisciplinarity apparent. But as this debate has swung internally, there continues to be a lack of practices and design strategists that have staked a claim at the seams of where architecture meets environment. This is where we would align ourselves (and Bracket has become a useful venue for curating practices and thinkers within that position).

And just to qualify a bit, we don’t see ourselves as (nor would we want to be) economists or ecologists. We prefer being architectural strategists – only we sometimes radiate outside traditional notions of the profession to more fully understand a context or a condition. And in that process, we don’t limit ourselves to a superficial treatment of the subject.

To return back to your reading, we are certainly sympathetic to Roger Sherman’s criticism of planning’s inability to respond to certain urban change, his call for architects to assume risk, and the power of entrepreneurial local anomalies to catalyze successive development. And being sympathetic to design incorporating new models of planning, we share his claim that “design strategy operates hand-in-hand with a business plan” (from Sherman and Dana Cuff’s forthcoming Fast-Forward Urbanism). For us, this is the difference between operating tactically and operating strategically. We like chess player Savielly Tartakover’s saying that “tactics is knowing what to do when there is something to do. Strategy is knowing what to do when there is nothing to do.” This ‘nothing to do’ can be interpreted as either 1) seemingly nothing possible to do; or 2) seemingly nothing needed to do. Both interpretations necessitate a more expanded understanding of the brief or context that precedes architecture. We prefer working when there is nothing to do.