Kazys Varnelis follows up his recent interview of Joseph Tainter (author of The Collapse of Complex Societies) by himself being interviewed, at Triple Canopy (whose last two issues on urbanism are indispensable):

Triple Canopy: You’ve argued that it’s no longer possible to rebuild existing infrastructures or, for that matter, to build better ones. And you’ve proposed “social engineering” and “human hacking” as keys to changing how we think of and how we use infrastructure. On the other hand, a quarter of the counties in Michigan are converting paved roads to gravel to save money. Do you still believe in the prospect of technology enabling us to salvage our increasingly chaotic, dilapidated built environment?

Kazys Varnelis: I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately. On the one hand, I still believe that a government initiative to bring infrastructure into the twenty-first century by opening data to everyone—not just leaving it in the hands of the technocratic elite—would make things better for everyone. We can see this in the ability to monitor traffic conditions in real time on Google Maps. If there is a jam in a certain area, our navigation system should route us around it.

But as I’ve been studying such possibilities over the past year, it’s become clear to me that there’s a danger to putting too much faith in the bottom-up model. During the past decade, there’s been a lot of fascination with bottom-up forms of organization. If these work at certain levels, they don’t work at others. In particular, they are unable to provide adequate structures of authority. This has been the typical lesson of revolutions: In the process of creating new governments, the revolutionaries fail or resort to authoritarianism…

I think we’re reaching that point [at which societal complexity becomes so “frustrating” and “unrewarding” that people walk away from it] rapidly. NIMBYism and legal constraints make much new hard infrastructure unlikely. One of the few projects that might get built, the high-speed rail line between LA and San Francisco, will take twenty years, assuming there are no delays. In contrast, the first transcontinental railroad took seven. We aren’t going to build our way out of this highly congested world. It’s going to choke us. This is a danger with any information-sharing mandate: It could build more complexity into the system! Does a light post need to share information? How about a traffic bollard? Probably not. But if you engineer them to do so, you add complexity and cost.

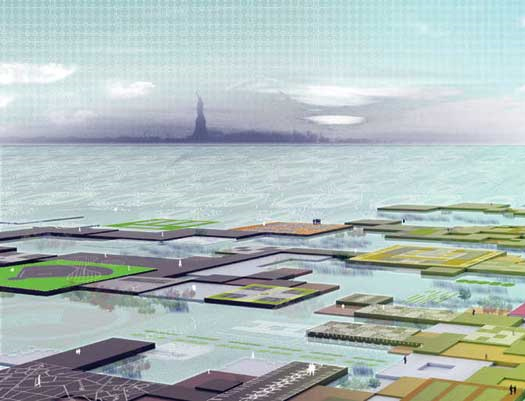

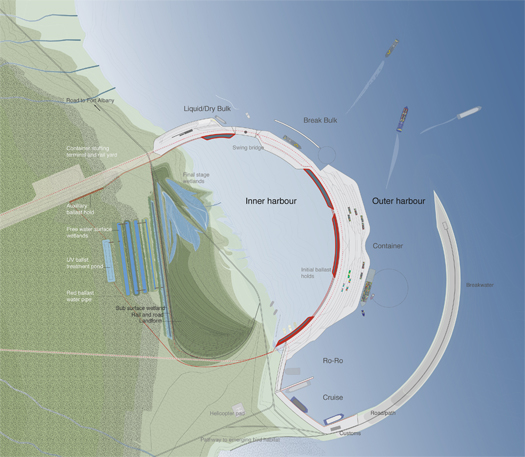

Read the whole interview for more on planning as megalomania, why architects ought to look to the Renaissance and postmodernism for clues on how to operate in the current economic climate, and the danger inherent in conceiving of architecture as an essentially technical discipline. I mentioned in the last post that a large box of reading material arrived last week, along with the Landscape Infrastructures DVD. I’m not certain what the appropriate balance is, but there’s something very interesting (and, I think, helpful) about reading the Varnelis-edited Infrastructural City (one of the items in that box and one which, to be simplistic and reductive, might be described as infrastructural pessimism) along with Landscape Infrastructures (which, to again be simplistic, might be described as infrastructural optimism).