[The Large Hadron Collider]

The end of a decade inspires a lot of list compiling; in that spirit, mammoth offers an alternative list of the best architecture of the decade, concocted without any claim to authority and surely missing some fascinating architecture. But we hope that at least it’s not boring, as this was an exciting decade for architecture, despite the crashing, the burning, and the erupting into flames.

The unfortunate thing about year-end lists is that they often devolve into self-congratulatory displays of one’s good taste. With that in mind, allow us to state at the outset that the purpose of this list is not to preen the superiority of our taste (we’re well aware that the critics who pen those boring lists have visited far more of the relevant architecture constructed this decade than we have), but rather to share a handful of the reasons that we’re genuinely excited about the future of architecture, and to hopefully engender a bit of that excitement in a reader or two. To that end, the items on this list have been selected to represent some of the most hopeful trends which impinge upon the territory of architecture (and, occasionally, landscape architecture, as the constant and intentional conflation of the two disciplines which is a mammoth trademark continues). You’ll discover that our criticism of boring lists consists primarily in their being confined to (a) buildings and (b) things built by architects, though our list includes both buildings and things built by architects.

In fact, “favorite” might be a better way to describe this list than “best”, but we’ve stuck with “best” because it’s more fun, as you can’t argue about “favorites”. With those disclaimers out of the way (and hopefully conveniently forgotten), in no particular order, mammoth‘s best architecture of the decade:

ORANGE COUNTY’S GROUNDWATER REPLENISHMENT SYSTEM

[Image of the reverse osmosis cylinders, which remove “viruses, salts, pesticides and most organic chemicals” from water being treated by Orange County’s wastewater reclamation plant, via Wired’s photo gallery]

With apologies to Matt Jones, whose piece for io9, “The City is a Battlesuit for Surviving the Future”, spawned great conversation last year, you might say that the Groundwater Replenishment System is a small step towards a new way of thinking about urban hydrology: the city is a stillsuit for surviving the drought. Intended to halt the traditional mass flush of urban effluent and wastewater into the ocean, Orange County’s latest addition to its wastewater infrastructure is “the world’s largest, most modern reclamation plant”, capable of turning “70 million gallons of treated sewage into drinking water every day”, according to the LA Times.

This capability, a staggeringly futuristic feat of engineering and technology, has unfortunately been derided as “toilet-to-tap” by opponents of wastewater reclamation, who fear the contamination of drinking water supplies. As a result of this short-sighted political opposition, the plant’s treated water is injected into the bedrock beneath the county, counteracting saltwater intrusion and replenishing underground reservoirs, rather than forming a closed loop of water use and reuse, but the potential for that closed loop is there, and there’s no doubt that the closing of water use loops will become an increasingly central infrastructural tactic for municipalities and governments facing decreased water supplies and rainfall in the coming decade. Closed water loops may even become as integral and expected a part of architecture as air conditioning is today (as a recent article in Landscape Architecture said, in what I thought was an unexpectedly beautiful phrase: “buildings are the new aquifers”); until then, we have the Groundwater Replenishment System.

Watch an eight-minute explanation of the function and purpose of the GWR System from the Orange County Water District, or scan the Orange County Water District’s headquarters in Fountain Valley on google maps; read a short overview of global efforts to utilize recycled sewage, at National Geographic.

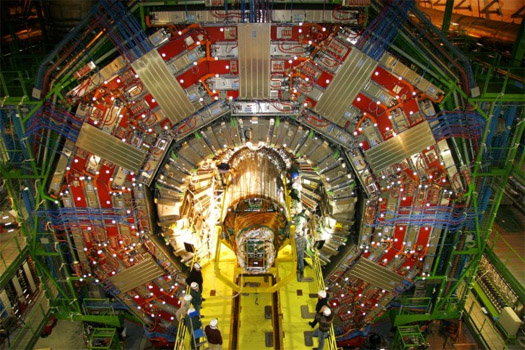

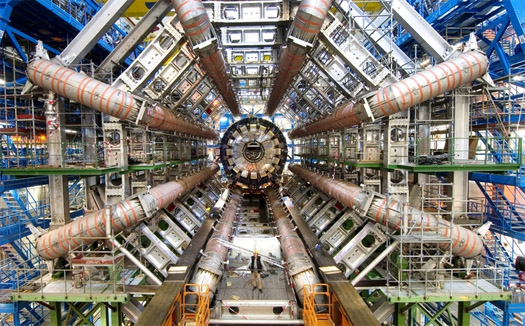

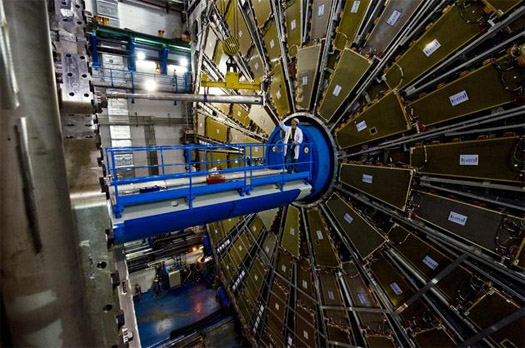

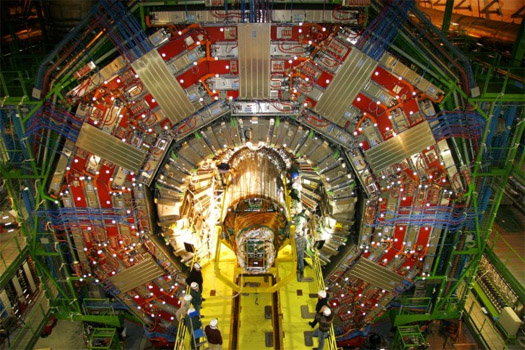

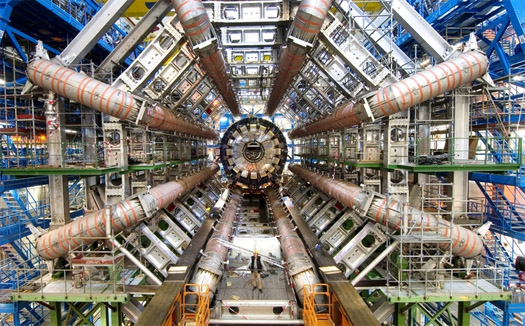

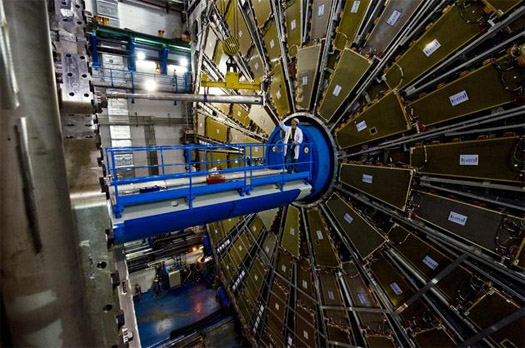

LARGE HADRON COLLIDER

[images of the LHC and CERN via Wired Science]

This recent Vanity Fair feature provides a succinct overview of the reasons that the LHC was the first and most obvious candidate for this list:

The L.H.C., which operates under the auspices of the European Organization for Nuclear Research, known by its French acronym, cern, is an almost unimaginably long-term project. It was conceived a quarter-century ago, was given the green light in 1994, and has been under construction for the last 13 years, the product of tens of millions of man-hours. It’s also gargantuan: a circular tunnel 17 miles around, punctuated by shopping-mall-size subterranean caverns and fitted out with more than $9 billion worth of steel and pipe and cable more reminiscent of Jules Verne than Steve Jobs.

The believe-it-or-not superlatives are so extreme and Tom Swiftian they make you smile. The L.H.C. is not merely the world’s largest particle accelerator but the largest machine ever built. At the center of just one of the four main experimental stations installed around its circumference, and not even the biggest of the four, is a magnet that generates a magnetic field 100,000 times as strong as Earth’s. And because the super-conducting, super-colliding guts of the collider must be cooled by 120 tons of liquid helium, inside the machine it’s one degree colder than outer space, thus making the L.H.C. the coldest place in the universe.

The Large Hadron Collider is an excellent example of a theme that runs through this list, ably described by BDLGBLOG‘s Geoff Manaugh in his book (and quoted here with apologies to dpr-barcelona, who I borrowed the use of this quote from):

“Architecture schools and publications today seem almost desperate for a new avant-garde –even for a “new Archigram”– but they seem only to be looking within the field of architecture to find it. For the sake of argument, let’s say that BP, with its offshore oil rigs, or the U.S. military, with its rapidly deployed instant cities, or private space tourism firms are the new Archigram. They, too, are experimenting with spatial technologies and structures. Is it possible that the “new Archigram” won’t involve architects at all –but will be, say, rogue engineers from the construction wing of an international oil-services firm?”

As we see it, the LHC falls easily into the long tradition of Architecture without Architects, but with scientists, engineers, and miners standing in for, say, traditional Saharan construction technologies and the vernacular architecture of the Mediterranean coasts; instead of timeless ways of building, a building that may have altered time itself.

Various blog coverage of the Large Hadron Collider of note includes Pruned’s post on the descent of the last of the LHC’s more than seventeen hundred magnets into the subterranean complex, BLDGBLOG’s speculations generated by the necessity of freezing an underground river in place in order to construct the complex, and the Large Hadron Collider tag in Wired Science‘s archives, which covers the birth and life of the LHC in exhaustive detail.

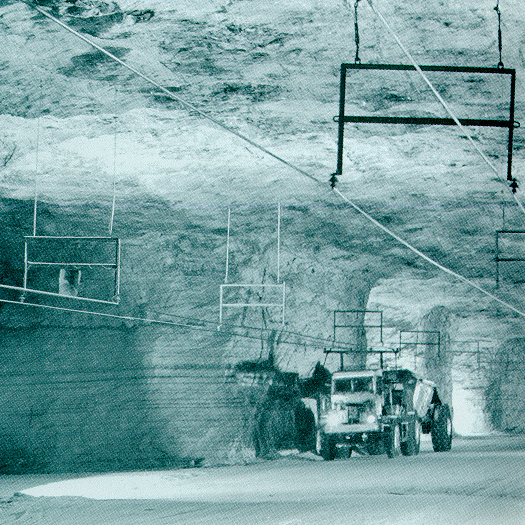

SVALBARD GLOBAL SEED VAULT

[images via SEED magazine slideshow]

A doomsday vault for when it all goes terribly, terribly wrong? Well, yes, but that’s not all the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is. Located in the Norwegian village of Longyearbyen, one of the world’s northernmost towns, the vault is a bank dedicated to the preservation of variety and dynamism, itself a seed for the regeneration of complexity in ecosystems. Ironically, given that mission, everything about the structure strives toward stasis: political and geographic locale; ownership and maintenance of the seeds; interior and exterior climate conditions; technology and construction. Like the LHC, Svalbard’s Seed Vault is sublime because of purpose and engineering, not aesthetic or theoretical vision — though the structure, again like the LHC, does not lack in aesthetic wonder.

Norway owns the Vault, but not the seeds it contains. The majority are varietals of staple crops from around the globe, sent by local seed banks across the globe to take advantage of the Vault’s offer of free storage. Unlike these local banks, the Vault is not meant for regular access. These seeds will only be reclaimed in situations of dire need. But those situations are not post-apocalyptic scenarios in which survivors begin a trek to Svalbard to salvage seeds, as rebuilding after catastrophic collapse, while perhaps a romantic scenario, is not the primary disaster which SGSV guards against. Rather, the Vault stands as a bulwark against the creeping (and probably inevitable) extinction of various crop strains and their valuable genetic data – perhaps even before we have had time to examine their potential.

Cary Fowler, director of the Global Crop Diversity Trust, identifies Svalbard’s mission in an interview with C-Lab in Volume 17, “Content Management”. He describes a crop called ‘Lathyrus,’ or Grass Pea, which is easy to grow, requires little water and fertilizer, and could “easily be the only crop you need to provide food for yourself and your family.” However, it is also toxic, and if you eat enough to ward off starvation, you have also eaten enough to paralyze yourself:

It’s an awful choice that the most unfortunate people on earth have, which is to starve to death or become paralyzed. That is where I think the seed vault comes in. Within this crop there is a fair amount of diversity, and some varieties have less toxin than others. We use the collections to breed new varieties that have all the great qualities I just mentioned without the bad quality. If we can do that, we can provide the poorest people on earth with a great insurance policy. In a sense, I know the attraction of the doomsday vault is doomsday, but I really see the whole see vault as something remarkable and positive

iPHONE

[Image from Urban Omnibus’s write-up on the “Museum of the Phantom City”, a fantastic iPhone application which lets the phone owner navigate the history of architectural proposals for the (paleo-)future of Manhattan as an extension of their experience of the physical city]

Much has already been written about the iPhone as an extension of both city life and architecture, by persons with better understanding of both the technology and its import, but we’d be extremely remiss if we failed to include a device with the capacity to so thoroughly transform the urban experience. Perhaps the most fundamental aspect of that transformation is the capacity of the smart or ‘app’ phone to serve as a window into additional layers of data on the city — often described as ‘augmented reality’ — while tying smart phone users into the network that maintains those layers of data. Smart phone users are not merely passive observers of the augmentation of the physical infrastructure of the city by networked data, but participate in the active construction of that data.

The interface between place and network appears likely to grow stronger, as the linking of network participation with location which first gained mass effect through the iPhone is strengthened and deepened by hardware and software advances, such as hyper-local trending topics on twitter, google goggles, wikitude, collective memory models, and the tools being developed by MIT’s Fluid Interfaces Group. Public utilities can utilize the collective intelligence of a city’s citizens to detect system malfunctions; citizens can develop tools to gather reports of failure within the urban system, collate those failures geographically, and pressure government to react using the collected data. And as the network becomes increasingly tactile, immediate, and geographically relevant, it can be expected to develop more direct interfaces with buildings.

If you doubt that the iPhone is appropriately considered an act of architecture, we suggest considering the argument discussed our recent post object fixations: urban systems are “defined most fundamentally not by structure and infrastructure, but by practice, action, and thought-process”; what act has more signficantly altered the practices and thought-processes of urbanites in the past ten years than the mass distribution of smart phones?

QUINTA MONROY

[images via Elemental]

Quinta Monroy is a center-city neighborhood of Iquique, a city of about a quarter million lying in northern Chile between the Pacific Ocean and the Atacama Desert. Elemental’s Quinta Monroy housing project settles a hundred families on a five thousand square meter site where they had persisted as squatters for three decades. The residences designed by Elemental offer former squatters the rare opportunity to live in subsidized housing without being displaced from the land they had called their home, provides an appreciating asset which can improve their family finances, and serves as a flexible infrastructure for the self-constructed expansion of the homes.

The first challenge that Elemental faced was a strict budgetary limit of $7500 (USD), the standard Chilean per-family housing subsidy. This subsidy would have to purchase the land, architecture, and infrastructure of the development, yet is only enough — at market-rate construction costs in Chile — to buy thirty square meters (322 square feet) of built space on such a center-city site. Because of this, social housing in Chile tends to be produced as outlying sprawl, where land can be bought more cheaply, allowing a greater percentage of the subsidy to be devoted to the architecture. Unfortunately, for reasons that are not fully elucidated in Elemental’s project description (though I am led to believe those reasons are the low value of the land social housing is usually built on and the low quality of the construction), social housing in Chile tends to depreciate in value, rather than appreciate, further miring families in poverty, as the housing subsidy is the largest single sum of aid that most impoverished families will receive from the Chilean government. If that movement could be altered — if the housing could be designed so that it appreciates rather than depreciates — it might be the difference between long-term poverty and a gradual climb towards sustainable familial self-sufficiency.

[The Quinta Monroy site in urban context, via google maps]

Elemental’s first decision was to retain the inner city site, a decision which was both expensive and spatially limiting: there is only enough space on the site to provide thirty individual homes or sixty-six row homes, so a different typology was required. High rise apartments would provide the needed density, but not provide the opportunity for residents to expand their own homes, as only the top and ground floors would have any way to connect to additions. Elemental thus settled on a typology of connected two-story blocks, snaking around four common courtyards, designed as a skeletal infrastructure which the families could expand over time:

We in Elemental have identified a set of design conditions through which a housing unit can increase its value over time; this without having to increase the amount of money of the current subsidy.

In first place, we had to achieve enough density, (but without overcrowding), in order to be able to pay for the site, which because of its location was very expensive. To keep the site, meant to maintain the network of opportunities that the city offered and therefore to strengthen the family economy; on the other hand, good location is the key to increase a property value.

Second, the provision a physical space for the “extensive family” to develop, has proved to be a key issue in the economical take off of a poor family. In between the private and public space, we introduced the collective space, conformed by around 20 families. The collective space (a common property with restricted access) is an intermediate level of association that allows surviving fragile social conditions.

Third, due to the fact that 50% of each unit’s volume, will eventually be self-built, the building had to be porous enough to allow each unit to expand within its structure. The initial building must therefore provide a supporting, (rather than a constraining) framework in order to avoid any negative effects of self-construction on the urban environment over time, but also to facilitate the expansion process.

Finally, instead a designing a small house (in 30 sqm everything is small), we provided a middle-income house, out of which we were giving just a small part now. This meant a change in the standard: kitchens, bathrooms, stairs, partition walls and all the difficult parts of the house had to be designed for final scenario of a 72 sqm house.

In the end, when the given money is enough for just half of the house, the key question is, which half do we do. We choose to make the half that a family individually will never be able to achieve on its own, no matter how much money, energy or time they spend. That is how we expect to contribute using architectural tools, to non-architectural questions, in this case, how to overcome poverty.

[Quinta Monroy shortly after construction of the initial framework and living space, but before the families have begun self-construction, via Elemental.]

Elemental, in other words, have exploited the values and aims of ownership culture (which mammoth has suggested understands the house to be first a machine for making money and only second to be a machine for living) not to support a broken system of real estate speculation and easy wealth, but to present architecture as a tool that can be provided to families. While the project is embedded with some of the assumptions of the architects (such as that faith in the potential of ownership culture, for better or worse), this tool is primarily presented as a framework, a scaffolding upon which families are able to make their own architecture. This seems like an important step — made visually apparent by the strong contrast between the simple lines of the initial framework and the colorful and varied familial additions — in the direction of what Lebbeus Woods describes as offering architecture as “the rules of the game”, or, the thinking he described behind a “capsule” which could offer architectural aid to people living in slums:

From the side of the slum dwellers, it might seem an unwelcome intrusion from outside, just another quick fix imposed by the economically advantaged on the desperately poor, serving the interests of the rich by transforming the slum according to their well-intentioned but—to the slum dweller–necessarily opposed values. It is especially important, then, that the transformative capsule enables the slum-dwellers to achieve their goals, serving their values, and does not reduce them to subjects of its designers’ and makers’ will. Inevitably, the values, prejudices, perspectives and aspirations of the designers and makers will be imbedded in the capsule and what it does. Therefore the slum-dwellers should, in the first place, have the right of refusal. Also, they must have the right to modify the capsule and its effects as they see fit. It cannot be a locked system, capable of producing only a predetermined outcome. The implication of these freedoms is that the capsule, whatever its capabilities, could be used to work against the intentions of its designers and makers. Because the effects of the capsule would be powerfully transformative, its possession would involve risk for all the groups, and individuals, involved.

Take a video tour of Quinta Monroy or watch a documentary about Quinta Monroy (in Spanish); construction photographs of a similar project by Elemental in Monterrey, Mexico; a brief article at Dezeen; a bit of commentary on the project as well as the stories of two of the inhabitants of the houses, at The Incremental House, a research blog by one of the 2008 Branner fellowship recipients.

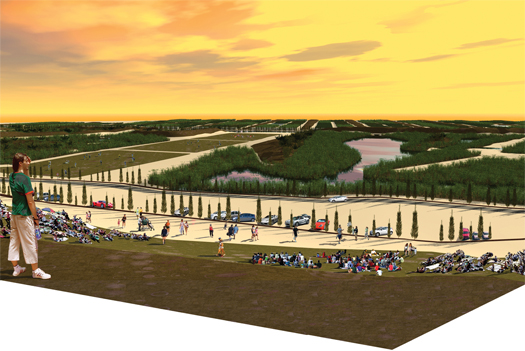

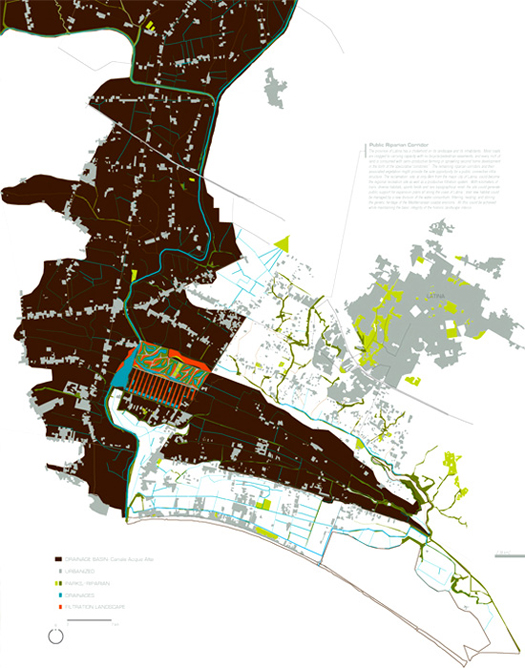

PONTINE SYSTEMIC DESIGN

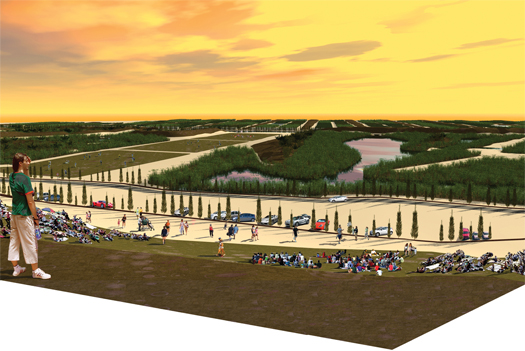

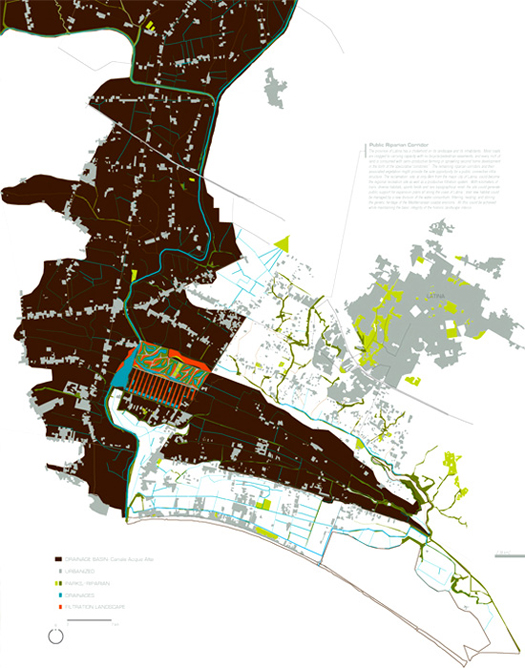

[Perspective view of P-REX’s proposed “wetland machine”, the regional master plan, and a factory and agricultural land within the watershed of the masterplan; images via P-REX, Pruned, and Google Maps, respectively]

The IBA Emscher Park — most famously symbolized by Peter Latz’s Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord, a fantastic recreational park that recycles the industrial past for contemporary recreation without losing the melancholy charm of the “natural decay and dilapidation of the site”, but as a whole, “[embraces] more than 120 distinct projects” scattered through out the Ruhr — is perhaps the exemplary global example of how a systematic program of landscape and architecture can combat regional decline in the wake of de-industrialization. If this list were a list of the best architecture of the previous decade, the Emscher Park would be the first item on the list. However, while the Emscher Park is a good and kind way of dismantling an industrial region in response to global economic trends, incorporating the repair of the damaged ecology of that region into the construction of new spaces for recreation and provision of the physical infrastructure for cultural programming, it is nonetheless fundamentally a deconstructive program. It is only intended to preserve the industrial infrastructure of the past as museum, not to re-purpose that infrastructure as the foundation of new production economies and new industries.

Which is why projects such as P-REX’s Pontine Systemic Design, a regional master plan which proposes the transformation of a portion of Italy’s drained Pontine Marshes into a wetland machine which serves to repair and maintain ecological balance in an industrial and agricultural region while that industry and agriculture remains vital, are so important. A 2008 NYTimes article explains the intentions of Alan Berger, the landscape architect who founded P-REX:

[Berger] is recommending a radical solution: not so much to restore the environment as to redesign it.

“It is so ecologically out of balance that if it goes on this way, it will kill itself,” said Alan Berger… who was excitedly poking around the smelly canals on a recent day… You can’t remove the economy and move the people away,” he added. “Ecologically speaking, you can’t restore it; you have to go forward, to set this place on a new path.”

Designing nature might seem to be an oxymoron or an act of hubris. But instead of simply recommending that polluting farms and factories be shut, Professor Berger specializes in creating new ecosystems in severely damaged environments: redirecting water flow, moving hills, building islands and planting new species to absorb pollution, to create natural, though “artificial,” landscapes that can ultimately sustain themselves [emphasis ours].

The Pontine Systemic Design represents exactly the sort of “reformulation” of the “historically suppressed” “biophysical landscape” “as a sophisticated, instrumental system of essential resources, services, and agents that generate and support urban economies” which Pierre Bélanger called for in his recent article in Landscape Journal, “Landscape as Infrastructure” (PDF). P-REX’s website describes the elements of the wetland machine which lies at the heart of the regional master plan:

Choosing a gigantic, consolidated wetland site will likely be more viable in the complex patchwork of land ownership. Given Latina’s situation, distributed treatment areas would be both enormously complex to purchase and ineffective to manage. The Wetland Machine’s dimensions are directly related to the amount of wetland area needed to treat the amount of water in the Canale Aque Alte—the major collector for this highly polluted zone. At 220 l/s, with a load around 50+ mg/l of N, at least 2 square kilometers of treatment wetland will be required. The design retro-fits and widens existing canals to serve as flow distributors. Furthermore, soil cut/fill operations are used for terraforming shallow ridges and valleys to hold/treat water and make raised areas for new public space and program. At 2.3 sq. km., the new wetland machine will drastically improve the regional water supply and provide needed open space for recreation. At only 6 km from Latina, the site could house programs and environments almost completely lacking in the region—large open landscapes with diverse vegetation. Extensive edge habitat diversity or programs—shallow shoals for juvenile fish and swimming, starker edges for fishing and water storage.

The landscape, in the form of a constructed wetland, becomes the central hydrological infrastructure of this polluted agricultural and industrial watershed, a transformation firmly situated within the understanding of landscape infrastructures as the key component of “urban ecologies”, which Bélanger delineates in “Landscape as Infrastructure”:

Endogenous and exogenous processes, such eutrophication, combined-sewer overflow, sediment contamination, invasive flora, exotic fauna, depleted water reserves, and seasonal floods can no longer be perceived as isolated incidents, but rather as part of large, constructed hydrological ecolog that is entirely and irreversibly connected to the process of urbanization. The slow, yet large-scale accumulated effects of near-water industries and upstream urban activities once considered solely at the scale of the city, are now more effectively understood at the scale of the region.

Insofar as the P-REX’s design represents a step in the direction of this regional consideration of landscape infrastructures, it provides hope that architecture and landscape architecture may yet have some agency in addressing in what Berger has described as “the larger-scale environmental issues that are currently affecting urbanized regions”.

Though the project is not yet built, as far as I am aware P-REX and the provincial government are still collaborating on the planning and design of the project, with every intention of seeing it through construction; and, at any rate, mammoth has no distaste for entirely speculative projects. Pruned has an excellent summary of the project, which includes higher-resolution images of the project provided by P-REX. I wrote a brief piece two years ago attempting to situate Berger’s design within the cultural landscape history of the Agri Pontini, though the efficacy of that effort was surely inhibited by my lack of knowledge of Italy; at any rate, I still think the contrast/parallel between the early 20th century pump machinery which drains the Pontine Marshes and the wetland machine proposed by Berger is fascinating. Abitare did an excellent recent interview with Berger touching on the Pontine Marshes but dealing primarily with Berger’s research techniques, methodologies, and thoughts on the discipline of landscape architecture.

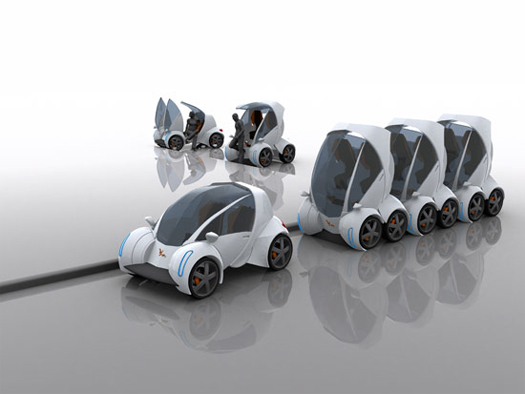

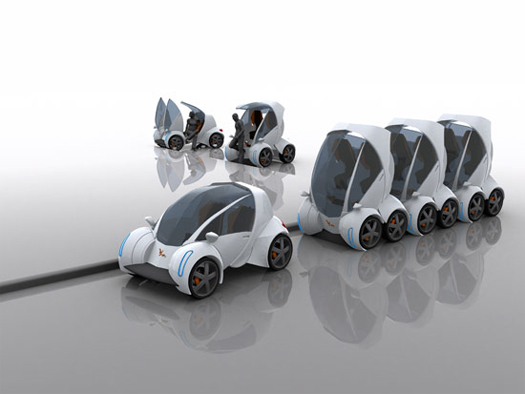

CITYCAR

[Images via CNET]

Developed by MIT’s Smart Cities group, headed by William Mitchell, CityCar is:

…a foldable, electric, two-passenger vehicle for crowded cities. It uses Wheel Robots—fully modular in-wheel electric motors—that integrate drive motors, suspension, braking, and steering inside the hub-space of the wheel. This drive-by-wire system requires only data, power, and mechanical connection to the chassis of the vehicle. Wheel Robots have over 120 degrees of steering freedom, allowing for a zero-turn radius and 90-degree parking (sideways translation); they also enable the CityCar to fold by eliminating the gasoline-powered engine and drive-train. Folded, the CityCar is very compact (roughly 60” or 1500mm), with an on-street parking ratio of at least 3:1 to traditional cars. It is also lightweight (1000lbs) and modular, and automatically recharges when parked, reducing battery needs and excess weight. The CityCar has two use models: private (traditional ownership), and shared (Mobility On Demand, high-utilization, one-way shared systems like Paris’s Vélib’ bicycle-sharing program).

While the technology behind CityCar is interesting in and of itself, architecturally the most interesting aspects of CityCar are the dynamically-priced markets for electricity and roadspace which Smart Cities envision developing around the second, shared use model. Through GPS systems embedded in the cars, congestion pricing could be altered in real-time in response to the flow of traffic through a city’s streets, achieving a far more perfect market reflection of the urban condition than could be imposed by any top-down model. Similarly, CityCars — being essentially mobile batteries — would be tied through their recharging stations into a city or region-wide smart grid, purchasing electricity at cheap rates during off-peak hours from the grid and selling it back to the grid at higher rates during peak hours, at once exploiting the market potential of the smart grid and becoming an essential component of the grid. The CityCar, then, is not merely a vehicle traveling across fixed infrastructures (or a smaller version of today’s cars), but is itself a distributed infrastructure, resilient, flexible, and responsive to input from the city.

A Boston Globe article highlights some of the pragmatic and regulatory difficulties that will be faced in attempting to bring the CityCar to mass realization; interestingly, this CNET article notes that Hawaii — where residents often travel from island to island without their cars — has shown interest in CityCar as a mass transit system; read a roundtable conversation between William Mitchell and Robin Chase (founder of the car-sharing service ZipCar) at the Next American City; read a feature on Chase at Urban Omnibus; this Places article discusses the notion of “fracture critical” infrastructures, and how their potential for disastorous failure suggests the necessity of resilient and flexible infrastructures.

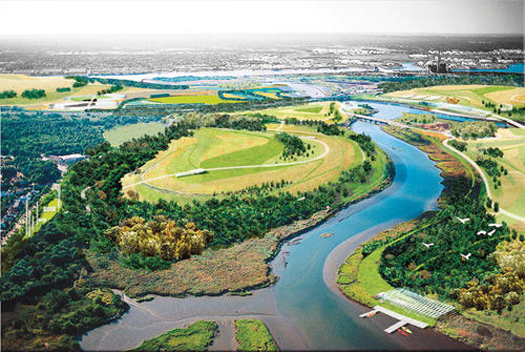

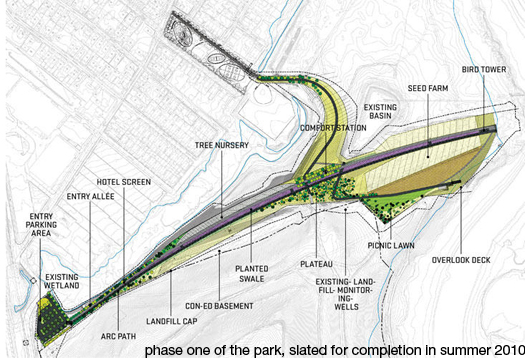

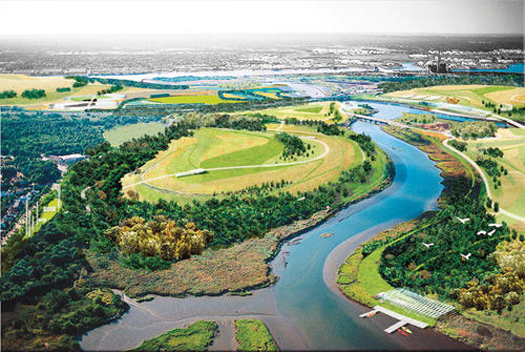

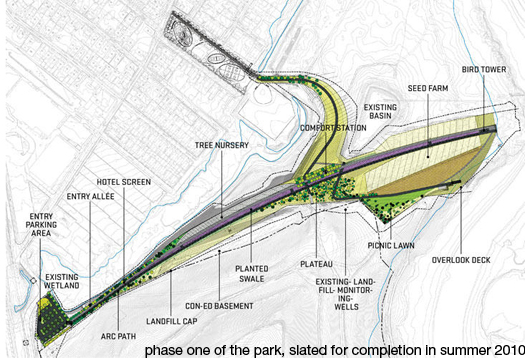

FRESH KILLS

[images via Metropolis slideshow]

There was a lot of talk in the past decade about how landscape architecture — whether in the slightly older guise of landscape urbanism, or in the more fashionable and current guise of landscape infrastructure — would come to dominate urban design practice. Both architects and landscape architects, from Koolhaas to Corner, noted that the contemporary city is dominated by flatness, that the singular architectural object is powerless to overcome the conditions of that flat city, and that landscape architects are seemingly well-equipped, being situated at the boundaries of ecology (with its emphasis on process and flow), architecture, and urban planning, to operate on flat yet incestuously complicated cities.

Yet that potential has been largely unrealized. Designers, even in competition and academic endeavors (to say nothing of what has been built) stuck with what they knew: overtly formal, often beautiful, but ultimately stale master-planning exercises. The influx of data-based and algorithmic methods of indexing has done little to shift this paradigm; if anything, it has reinforced the tendency to resort to the beautiful drawing because of the ease with which it can be created, and the veneer of systemic complexity they grant a project. What use is the diagram when the plan is indistinguishable from it?

New York City’s Fresh Kills competition and the on-going work by Corner’s Field Operations, the competition winners, is one of the few examples that buck that trend, demonstrating the ability of an office led by a landscape architect to produce a synthesis of ecological, urban, social, and infrastructural processes on a large scale within an extremely complicated urban system. This kind of work, of course, operates intentionally on long time scales, and so it is perhaps not surprising that even Corner, probably the best-known of the landscape architects who joined the first wave of landscape urbanists, has only completed one major landscape (at least as far as I’m aware), the rather disappointing High Line.

What is particularly exciting about Field Operations’s Fresh Kills for landscape architects is that this massive new park isn’t being built so much as it is being grown and cultivated, thereby realizing a firm reliance on the flow and flux of ecologies as not just inspiration for design, but as the tool of design, as is explained in Andrew Blum’s 2008 article for Metropolis on Corner:

Corner saw [Fresh Kills] as a proving ground—not just as a park but for landscape architecture as a whole. It stacked up all the challenges he had been wrestling with: contaminated lands, exhaustive environmental reviews, competing community interests, glacially slow (if not totally absent) funding, and the opportunity to create an aesthetic unencumbered by Romantic landscapes. (In all of this, Corner was influenced by the landscape architect Peter Latz’s Landscape Park Duisburg-Nord, which was mostly completed by 1999.) “It was: Look, this is a landfill, it’s a regulated landscape, the soil is atrocious, how can you imagine a park here?” Corner says, describing his initial thought process. “It’s not an exercise of trying to design a fantastic park; it’s an exercise of trying to design a method to get from what it is now to something that is green, public, and safe. And that process would then produce a park that had very unique spatial and aesthetic experiences and properties.”

Corner called his scheme Lifescape, and the notion at its heart, part ecological and part poetic, came out of the earlier thinking: to grow the park, to reengineer the site as a “self-sustaining ecosystem,” an “autopoetic agent”—like a cell. One of the biggest challenges at the site was covering the mounds with at least four feet of soil, to make them safe for picnicking; Lifescape imagined the park growing that soil. “It’s easy to sit and dream up fantastic things,” Corner adds. “The trick is to dream up fantastic things that are smart with regards to the realities at stake.”

There’s still a lot to prove in this, um, proving ground — but mammoth suspects that landscape architecture will need more projects like Fresh Kills, not less, if it is to flourish in the next decade.

Of further interest might be this critique of Fresh Kills from Mario Ballestros, as well as this response to that critique from the official Fresh Kills blog and another response to the same critique which I posted a while ago at Eatingbark.

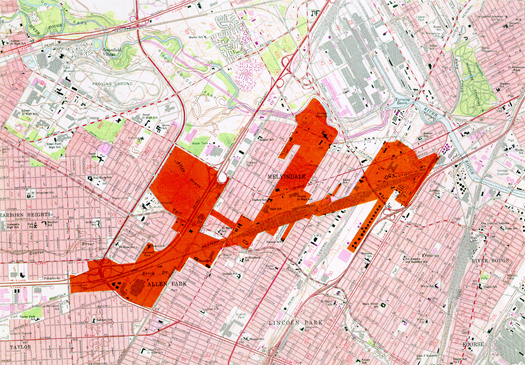

CHINA’S HIGH SPEED RAIL NETWORK

[image via Wikipedia]

The massive network of rail-lines, including conventional rail but particularly high speed rail, now spanning vast portions of China (and growing exponentially through the coming decade) is perhaps the best example of the continued relevance of the infrastructural “superproject” to emerge in the past decade. Nonetheless, we debated whether or not it belonged on this list and, rather than assemble our points into a coherent argument, thought we’d share that debate directly. You’ll note that we’ve entirely skipped over the question of whether a rail network can or should be considered architecture at all.

Stephen: I’m not yet convinced China’s high-speed rail belongs on the list. It’s not terribly different from any other high speed rail system in how it affects the country, how it came to be, or (as far as I know) any particularly impossible engineering condition which needed to be overcome. It’s not a triumph of project management or marketing, of building a massive infrastructural project despite difficult political or economic circumstances, because China is $loaded$ and, as a single-party state, doesn’t face the sort of political entanglements which make rail so difficult to build in the United States.

You mentioned earlier that it is an example of the continued relevance of the infrastructural superproject… in what way? As economic stimulus? As a nation-building ‘look at us’ project? Some other fashion? I am concerned all we learn from this project is that China can do whatever it wants – at which point, its just a Pretty Cool, Really Big Project.

Rob: I think that definition of “continued relevance” is too narrow. Sure, it’s most definitely not an example of an infrastructural building program which could be duplicated in a modern western state – but most states aren’t modern western states.

Stephen: Most states aren’t China either.

Rob: No, but it’s tremendously relevant to the future of China, and one in five people in the world lives in China.

Stephen: True. You know I’m as big of a high-speed rail supporter as anyone, considering its ability to act as both near-term and sustained economic generator.

Rob: And while it’s true that most states aren’t China, there are other big, functionally-single party regimes – Russia, for instance.

Stephen: This project serves largely the same function as other HSR networks around the world. Does it qualify as a best-of project just because it exists? Does China building the rail system prove a massive infrastructure project is relevant to Russia?

Rob: If it proves that it is (a) possible and (b) will have important effects on urbanization in that country, then, yes.

Stephen: Maybe a new, enormous pipeline is more relevant to Russia… so the question is, what exactly is China’s HSR proving? That HSR projects in particular are worthwhile, or that any large infrastructural project is – as long as it is fine tuned to the needs of a region, with the political and economic conditions present to enable its creation? And if it’s the latter, I’m inclined to say “Well, of course that’s true!” But then, maybe you and I operate in a bubble where the value of the Big Infrastructural Project is taken as a given, and outside that bubble, reinforcing the relevance of the Big Infrastructural Project isn’t a bad idea, however disappointing it may be that they are only possible in select conditions.

Rob: I’m more convinced now than I was at the beginning of the conversation that it belongs. At the beginning I was ready to throw it out, but now I’m convinced it represents a major trend in infrastructure which we’re otherwise ignoring. I think the last point you make as a devil’s advocate is key: while the acceptance of the continued value of large infrastructural projects may be a current idea within our circles, I doubt that it is so widely agreed.

[Map of China’s current and proposed high-speed rail connections via the excellent Transport Politic]

Stephen: Right. China’s HSR is a best-of-decade project because of its function as a signifier for the relevance of many types of large infrastructural projects, even if they are only possible in select areas. It’s in because it’s important in defining the urban future of China, as other sorts of projects might be for their respective countries. I think it’s instructive to contrast it against some other projects on this list which are better able to integrate themselves into areas without the benefit of a powerful centralized authoriy, like the Orange County Wastewater system or CityCar. Projects which are smaller, lend themselves toward incremental expansion, and minimal disruption of current systems, especially land-ownership. Those projects are often geared toward the remediation of damaged or obsolete infrastructures, whereas the Chinese HSR system is being introduced in as near a blank-slate condition as is possible in the twenty-first century. Not only do projects in non-authoritarian regimes need to be smaller and nimbler, but they are generally reactive. The fear of a broken system must exceed the fear of an angry mob of NIMBYs before action is taken. Appealing to the prospect of a better future is — unfortunately — quite often impossible.

Newsweek has an article about China’s High Speed Rail network here; images of the network can be found here at Treehugger; map of existing rail lines here; discussion of the scale and importance of this project relative to China as compared to HSR endeavors by other countries, here.

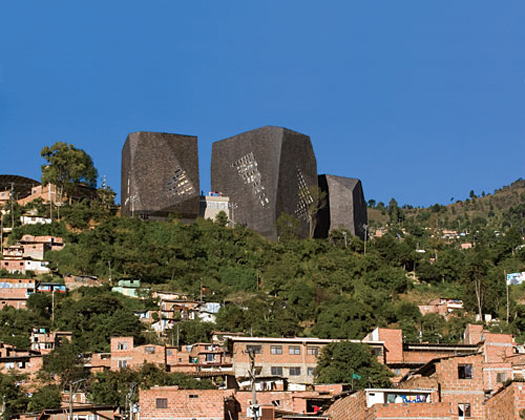

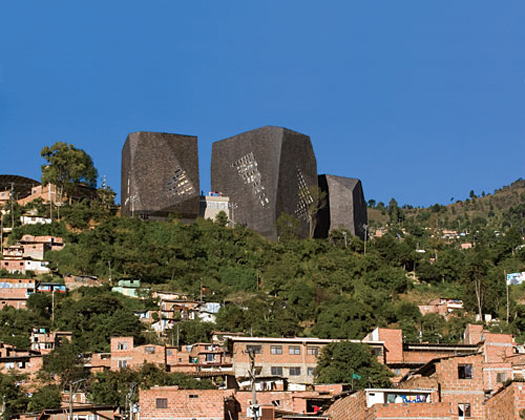

PARQUE BIBLIOTECA ESPANA

[images via Architectural Record]

Parque Biblioteca España is one of a number of notable projects built in the past decade in Medellin, Colombia, whose exceptionally progressive mayor, Sergio Fajardo, is using infrastructure, landscape, and architecture to spark renewal and combat systemic poverty. Much as Elemental’s Quinta Monroy made architecture a legible toolset for the residents of one city block in Iquique, the program of infrastructural development in Medellin has deployed architecture and landscape across the entire city, providing the city’s residents — and the inhabitants of the mountainside “comunas”, in particular — with an infrastructural toolset to rebuild their city and neighborhoods. Once the headquarters of Pablo Escobar, wracked by corruption and violence, and described as “the murder capital of the world”, Medellin has been transformed by an emphasis on public culture, shared spaces, and transparency. The Metro de Medellin was extended into the comunas by the construction of Line K, a public-transit cable car which replaced tedious and slow two-hour bus rides down the steep mountain side with a fast and comfortable twenty-minute ride, sparking the growth of community businesses in the comunas. A botantical garden located in the dangerous neighborhood of Moravia was renovated to remove walls, symbolically opening the garden to the community, and upgraded with a striking new central pavilion under which cultural events are organized and attended. The additions are both as small as the introduction of staircases connecting mountainside homes and as large as the system of five library parks, which includes Biblioteca España, providing safe and open places for meeting, playing and learning in the heart of the comunas.

[Passengers ride Line K, via the NY Times]

I highly recommend this slideshow from Medellin, taken by Quilian Riano (formerly fruitful contradictions, now @quilian on twitter and one of the two people behind DSGNAGNC), as well as Riano’s post at his Archinect school blog after visiting Medellin; the New York Times ran an article a couple years ago on Fajardo and Medellin; an Architectural Record article describes Parque Biblioteca Espana.

KIVA

[Modesta Tabanao in her general store in the Philippines. She received a loan of $225 “to purchase additional inventory and working capital” and is on-track to repay the loan over its nine month term.]

If the recent flury of projects in Medellin shows how traditional infrastructure tactically deployed can revitalize a city, Kiva shows how a non-traditional monetary infrastructure can do the same:

In 2004, Matt Flannery and Jessica Jackley witnessed the power of microfinance firsthand while on a trip which would become a life-changing experience. Visiting East Africa – Jessica conducting impact evaluation surveys for Village Enterprise Fund and Matt filming interviews with small business entrepreneurs – they were able to see and hear firsthand how small grants of only $100 – $150 had been used to build small businesses which could then support a family. They heard stories of people who were able to sleep on mattresses instead of dirt floors, afford to take sugar in their tea daily instead of occasionally, and buy fresh fish for their families a few times every week rather than once a week. Instead of meeting the poor and helpless, they found themselves meeting successful entrepreneurs who had generated enough profits from their small businesses to create a real impact on their standard of living.

Kiva is an infrastructure for distributing relatively small amounts of money to entrepreneurs, particularly in developing countries. Its brilliance is the realization that people would rather give to individuals — other people — than to an organization. Rather than sell you on a particular charitable mission, Kiva’s website engages donors by encouraging them to become stakeholders in the economic future of specific recipients. It displays their stories and, importantly, their business and repayment plans. Kiva, like those networks of physical structures more commonly understood as urban infrastructures such as roads, sewers, and powergrids, is fundamentally characterized by the properties of connection and transmission, which enables it to have widespread effect on cities across the globe.

Mammoth has written frequently about the city as it is constructed by complex interactions between systems, economies and societies, and argued that architects should engage this context. If one accepts this set of relationships as not merely descriptive of the processes within a city, but as the fundamental material of the city, more basic to the nature of urbanity than skyscrapers or freeways, how can the invention and deployment of Kiva not be considered an act of urban design? Kiva is infrastructural urbanism at its purest: unconcerned with directing the formal evolution of the city, focused instead on generating the financial mechanisms which enable citizens to participate in reshaping the city. These qualities make it n effective agent in some of the most informal urban conditions on the globe, conditions which confound traditional architectural response.

[PLOT’s “Clover Block” scheme, an unsolicited proposal for public housing in the city of Copenhagen which generated enough public interest to provoke a competition for the design of public housing on the site, via rory hyde dot com blog]

Kiva also suggests hopeful and alternate models of architecture practice, perhaps beginning to incorporate or co-opt a similar infrastructure in place of the traditional financier-client-architect funding model. Studies like the Office of Unsolicited Architecture and this post by FASLANYC begin to hypothesize what such a model might look like. They compliment financial experimentation found in projects such as these documented by Rory Hyde, architectural outfits like Supersudaca, and practices like Parking Day. We’re not sure how (or even if) the infrastructure Kiva has developed for financing entrepreneurs is scalable to the development of an architecture or landscape project. But mammoth believes that the dynamic between client, financier, and designer provides fertile ground for experimentation, and we hope lessons learned from Kiva can be applied to architecture in the coming decade.

[This post was co-authored by Stephen and Rob; we’d love to hear what we’ve gotten wrong (and why!), as well as what we’ve missed; we’ve got a handful of near-misses for this list in hand that we’ll hopefully get around to writing about soon.]