[A water tank stands in Brooklyn, festooned with cellular antennas, photographed by flickr user Dreamer7112.]

From the Franklin Stove, and the Stetson Hat, through the Evinrude outboard to the walkie-talkie, the spray can, and the cordless shaver, the most typical American way of improving the human situation has been by means of crafty and usually compact little packages, either papered with patent numbers, or bearing their inventor’s name to a grateful posterity…

True sons of Archimedes, the Americans have gone one better than the old grand-daddy of mechanics. To move the earth he required a lever long enough and somewhere to rest it — a gizmo and an infrastructure — but the great American gizmo can get by without any infrastructure… The quintessential gadgetry of the pioneering frontiersman had to be carried across trackless country, set down in a wild place, and left to transform that hostile environment without skilled attention. Its function was to bring instant order or human comfort into a situation which had previously been an undifferentiated mess…

At this point we have seen enough of the basic proposition to formulate some generalized rules for the American gizmo, and examine its consequences in design and other fields. Like this: a characteristic class of US products — perhaps the most characteristic — is a small self-contained unit of high performance in relation to its size and cost, whose function is to transform some undifferentiated set of circumstances to a condition nearer human desires. The minimum of skill is required in its installation and use, and it is independent of any physical or social infrastructure beyond that by which it may be ordered from catalogue and delivered to its prospective user.

– Reyner Banham, “The Great Gizmo”

A handful of recent posts (Life Without Buildings, Markasaurus, Robert Sumrell) have noted that the iPhone may be the single industrial product which best exemplifies both the continuance and the evolution of Banham’s notion of the peculiarly American gizmo. Perhaps the most important piece of that evolution is the move away the independence of the gizmo, which Banham’s repeated definitions, quoted above, hammered home as one of the defining characteristics of this class of industrial products.

The iPhone, however, is not only dependent upon highly developed systems in its production, as Banham acknowledges all such objects have always been, but is also now equally dependent in its operation upon a vast array of infrastructures, data ecologies, and device networks. Even acknowledging this, though, and realizing that its operative value comes from its ability to tap those data ecologies and attendant socially-constituted bodies of knowledge, it is still possible to miss the landscapes that it produces. Until we see that the iPhone is as thoroughly entangled into a network of landscapes as any more obviously geological infrastructure (the highway, both imposing carefully limited slopes across every topography it encounters and grinding/crushing/re-laying igneous material onto those slopes) or industrial product (the car, fueled by condensed and liquefied geology), we will consistently misunderstand it.

Take a single instance of iPhone use — Jimmy Stamp’s afternoon of coffee-shop sleuthing in Brooklyn, for example. Think what a vast array of landscapes are tenuously tethered to that single moment:

A. PRODUCTION: THE GIZMO AS A GEOLOGIC EXTRACT

First, we might consider the iPhone as a geologic extract, tracing backwards from the gizmo-in-hand to the direct effect of the gizmo on the surface of the earth, using two of the most prominent links in that chain of effect, mines and factories.

MINES (EXTRACTION)

A single iPhone is composed of 135 grams of material, including stainless steel, plastics, glass, a lithium-ion battery, and, perhaps most crucially for the tactile experience of iPhone ownership, a touch-screen display weighing in at 12.5 grams, just under one-tenth of the total weight of the device (PDF). To capture the motion of the user’s fingers, that touchscreen employs a technology known as “Project Capacitive Touch” sensing, which registers movement and pressure with electrically-charged strips of the transparently conducting solution indium tin oxide (In2O3 and SnO2). The key and most expensive component in that solution is the rare metal indium, which is not mined directly, but typically produced as a valuable by-product during the processing of zinc ores (though, owing to increasing demand and limited supply, it is increasingly recycled from manufactured products).

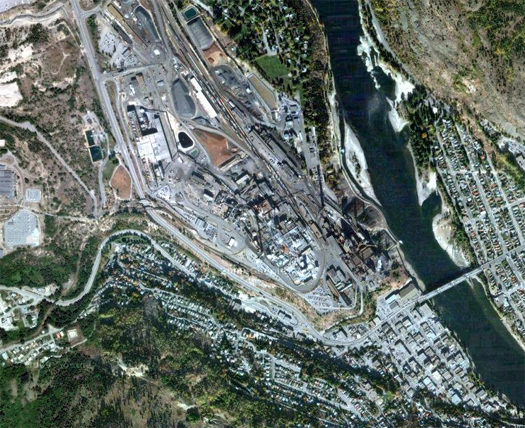

Canada is one of the world’s leading producers of indium, producing approximately fifty tonnes a year, a quantity which is exceeded only by China (330) and Japan (60). Within Canada, the single facility producing the greatest quantity of indium is Teck Resource’s refinery in Trail, British Columbia, which processes zinc ores hauled from the Red Dog pit mine in northwestern Alaska. Such mines and refineries, scattered across the globe in the aforementioned countries, as well as South Korea, Belgium, Russia, and Peru, are the iPhone’s landscape of extraction.

FACTORIES (ASSEMBLY)

While Apple is notoriously secretive about the iPhone’s supply and manufacture chains, reports from both Reuters and the Wall Street Journal indicate that the iPhone is manufactured in Hon Hai Precision Industries’ enormous Shenzhen plant, the Longhua Science and Technology Park, which employs over a quarter of a million people behind its walls and security gates. The facility’s factories, dormitories, hospital, restaurants, bank, basketball courts, executive offices, and cafes cover a square mile of terrain, at once company town and infrastructural city.

B. OPERATION: THE PHYSICAL TRACE OF INVISIBLE INFRASTRUCTURES

Second: while the act of locating a trio of Brooklyn coffee-shops does indeed depend on the operative ability of the iPhone to tap what Life Without Buildings describes as a series of “invisible infrastructures — locative data, telecommunications networks, reviews, news, images, information” — these invisible infrastructures do not lack traceable landscape impacts1.

SERVER FARMS (COLLATION)

It’s nearly impossible, of course, to say which servers caught those mapping requests for Cafe Pedlar, Marlow & Sons, and Blue Bottle Coffee. But we can query representatives.

As Google is, like Apple, quite secretive about the details of the physical loci of its immaterial product, the locations of less than half of Google’s American data centers are known, with those known centers spread between California (five centers), Oregon (two), Georgia (two), Virginia (three), Washington, Illinois, Texas, Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina, Oklahoma, and Iowa.

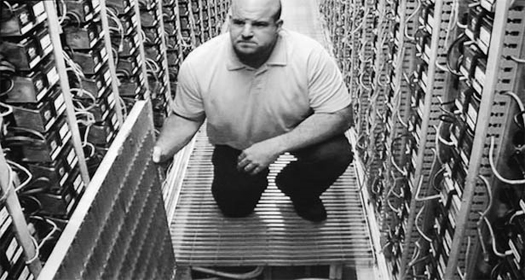

The first of these data centers to be constructed is in The Dalles, Oregon, and “includes three 68,680 square foot data center buildings, a 20,000 square foot administration building, a 16,000 square foot ‘transient employee dormitory’ and an 18,000 square foot facility for cooling towers”. Like Google’s other data centers, the Dalles facility consumes enormous quantities of electricity (estimates range from 50 to 100 megawatts — somewhere between a tenth and a twentieth of the capacity of an average American coal-fired power plant), generating similarly large quantities of heat, which necessitates locating the centers by significant water sources for the chillers and water towers which cool the servers.

Inside, the data centers are filled with standard shipping containers, each container packed with over a thousand individual servers running cheap x86 processors: anonymous, modular data landscapes, the nerve centers of America’s conurbations, their standardization and dull rectilinearity indicating extreme placelessness, but contradicted by the logistical logic of water bodies, energy sources, and transmission distances which governs their placement.

CELL TOWERS (TRANSMISSION)

With the materials extracted, the object assembled, and the data collated, the final step in this abbreviated tour is the transmission of that data from the server farms to the individual gizmo, a step which is enabled by ubiquitous cell towers and antennas. A quick query at AntennaSearch.com, a database of transmission tower and antenna permits and registrations, locates six hundred and seven antennas and seventy-nine towers within two miles of the neighborhood (Park Slope) where this particular search began2.

Again, it is nearly impossible to say which of these transmitters served as the “base station”, or central transmission point for the cell the search occurred within — all cellular coverage areas are divided into mapped cells, with the low power and range of transmission of the cellular phone allowing many phones in differentiated cells to occupy the same frequency without interference, by the extraordinary means of a legal fiction which compartmentalizes the air itself — but it is not difficult to pick out the sort of structures which might have done so: prosthetic antenna arrays, clinging to rooftops and water towers, or (much more rarely within Brooklyn) the tall and familiar standard cell tower, its silhouette looming over baseball fields.

Amazing piece, Rob. Have you see Ben Millen’s iPhone diagrams? Does a similar thing with cultural context:

http://www.benmillen.com/portfolio/?p=155

nice post.

i assume you’ve been keeping an eye on what andrew blum is working on? looks interesting, too, though perhaps slightly different.

the key difference is you are talking about the entire logistical system, from the infrastructure to the gizmo.

anyways, it is strange that we still maintain the dichotomy between the final link (the gizmo) and the rest of the system. the gizmo is just as much a status symbol as what Banham describes (essentially utilitarian).

also, it sounds like you are saying the iphone is not the american gizmo, but a hi-tech archemedian gizmo (since it requires an infrastructure), or some weird blend of both? i dunno. now i question whether it is applicable or if in fact it is something else?

Fasla: I would say that the gizmo is returning to a pre-electrical separation, with increased mobility and wireless technology. Before plumbing and electricity, the networks were purely commercial or social. Now, they’re a bit more hidden.

Also, the cables around the water tower in the first image is a wonderful expression of mathematics in architecture.

uarbchitect– good point. and to bring that full circle, perhaps when the network can be hidden the social status aspect of the gizmo can assert itself more clearly?

great post! was an absolute pleasure to read. Also loved the

…spatialization of the production into a exploitable geography of networks…on a totaly different note I wonder if somali Pirates use iphone (?) :)

[…] a preliminary atlas of gizmo landscapes ? mammoth" Until we see that the iPhone is as thoroughly entangled into a network of landscapes as any more obviously geological infrastructure (the highway, both imposing carefully limited slopes across every topography it encounters and grinding/crushing/re-laying igneous material onto those slopes) or industrial product (the car, fueled by condensed and liquefied geology), we will consistently misunderstand it. Take a single instance of iPhone use ? Jimmy Stamp?s afternoon of coffee-shop sleuthing in Brooklyn, for example. Think what a vast array of landscapes are tenuously tethered to that single moment…"(tags:eco phone comms ) […]

Fred: I had not seen Ben Millen’s diagrams, but those are fantastic. (Oddly similar to something Stephen and I tried to do in that Baltimore project which brought us together and which I think I’ve mentioned to you before, except we failed spectactularly.)

faslanyc: (a) Yes, I’m really looking forward to reading Blum’s book when he finishes it and (b) I suppose I would say that the iPhone is not Banham’s American gizmo, but it’s about as much an American gizmo as any contemporary thing, with the obvious caveat being that it’s assembled in a factory in China owned by a company based in Taiwan using materials extracted from mines all over the world, including the Canadian example above. But given that the role of globalization in shaping contemporary urbanism is quite widely noted, that’s not a stunningly original observation on my part.

цarьchitect: Great spot with the cables — I hadn’t noticed that.

saurabh: I don’t know about Somali pirates, but one of my favorite things about the iPhone is its rapid adoption by low-income communities (underserved by the traditional internet) — this report at NPR, which I think without taking the time to listen to it again discusses the use of iPhone applications to reach low-income Latino communities in Los Angeles for the census, being one small piece of evidence of that.

Also: just so its on the record that I’m speaking out of ignorance, I don’t have an iPhone.

This post brings together so many interesting topics. It seems that cities are made possible by infrastructure, so new forms of infrastructure could mean new forms of cities, both virtual and physical.

If traditional infrastructure is structure that expands human capabilities from below or within (based on the roots of the word and drawing upon your cyborg post), then new forms might be called something like parastructure (via Alex Schafren, para as beside, beyond, even faulty at times, but also expanding human capabilities). A parachute could be a good example, in combination with the planes, airports, satellites, and computer systems that make it possible for someone to jump from 14,000 ft and survive.

In a way, the earth is both infrastructure (under, within) and parastructure (beside, beyond), some parts human made, some not. And gizmos seem to be portable extensions of infrastructure, or possibly mobile parastructure?

By the way, I love that photo of the camouflaged cell array. :)

[…] all be playing with gadgets like the Electronic Tomato, that perhaps would not have given the iPhone a run for its money but was a “mobile sensory stimulation device,” nonetheless. We […]

[…] but all functioning in concert to support a heavily developed urban region. Much as mammoth has recently argued that the iPhone cannot be understood without understanding its participation in a diverse series of […]

[…] for their operation, Rob Holmes’ “mind-boggling update to I, Pencil“* looks at the landscapes of extraction, assembly and operation modern gadgets create. As Google is, like Apple, quite secretive about the details of the physical loci of its immaterial […]

[…] a preliminary atlas of gizmo landscapes – mammoth // building nothing out of something […]

[…] a preliminary atlas of gizmo landscapes – mammoth // building nothing out of something (tags: iPhone ecosystem) […]

I’m really loving the theme/design of your website. Do you ever run into any browser compatibility problems? A couple of my blog visitors have complained about my site not operating correctly in Explorer but looks great in Firefox. Do you have any recommendations to help fix this issue?

A key location involved with the movement of Red Dog material from Alaska to Trail, B.C. is located at Vancouver Wharves in North Vancouver, just east of the Lion’s Gate Bridge.

There are five Berths, numbered from west to east. At Berth 1 there is a moving Unloader crane which is primarily used for unloading Red Dog shipments for trans-shipment into railcars for transfer to Trail. The short shipping season from Alaska due to ice means that the crane is in high demand for a short period of time each summer. Annual production is stockpiled in Alaska and then shipped rapidly to get the product moved.

[…] "A Preliminary Atlas of Gizmo Landscapes" [Mammoth] (tags: geography) […]

[…] lifestyle we’ve become accustomed to is based on an extremely long supply-chain. Think of the support required for an iPhone to exist. (h/t Futurismic) You have mines, factories, server farms, copper an optical […]

Major thankies for the blog article.Really thank you! Really Great.

[…] Mammoth: “A preliminary atlas of gizmo landscapes” […]

[…] — they are, in fact, associated with specific landscapes of extraction, much like any other product of contemporary society. For the greater Los Angeles region, Irwindale is the locus of that extraction, a small city […]

[…] a useful reminder of the inescapable materiality of the city, a reminder which is often needed as technologies and thinkers tempt us to believe that cities can elude the gravity of material […]

[…] a preliminary atlas of gizmo landscapes – mammoth // building nothing out of something […]

[…] Ballet of iPod City”, ably connects two items that mammoth has recently written about, the iPod (and iPhone) factory-city in Shenzhen and Benjamin Schwarz’s critical essay on post-Jacobsian urbanists in the Atlantic Monthly: […]

[…] depends on a networked web of infrastructure to function at all. Consider Mammoth’s excellent preliminary atlas of gizmo landscapes. Consider the gap in the digital […]

[…] Atlas of iPhone Landscapes”, begins with the subject matter of a post from last year, “a preliminary atlas of gizmo landscapes”, but will spiral outward from “the spatial trace and organizational logic of patterns of […]

[…] classic architectural texts, one of which was Banham’s. Architect Rob Holmes, who has blog called mammoth, was struck by Banham’s description of “the most characteristic” of US […]

[…] our talk at Infranetlab’s Pamphlet Architecture launch at Storefront, a long update to the Preliminary Atlas of Gizmo Landscapes that Rob presented at MediaLab Prado, another student project or two, some excellent guest posts, […]

[…] written on the topic before, but I do highly recommend listening to and watching the talk today over Sunday […]

[…] and imaginary. The geologic lives in our bones (as calcium) and our cell phone screens (as indium tin oxide). The geologic “now” in which we live, and for which we design urban spaces and […]