In a recent back and forth between myself (Stephen) and Rory Hyde in the comments of On Finance, Rory noted:

To zoom out even further, are we just talking about ‘context’? To understand the context in architecture normally means literally to understand the site context – the two terms are used interchangeably – but as all of these other factors are now just as unavoidable as the site, they therefore warrant their own techniques (even personal styles) for dealing with them.

I think that’s right. ‘Context’ is probably a useful term around which we can catalyze discussions problematizing the relationship between architecture, financing, politics, marketing, culture. Last week, Rob and I were talking a bit about how engaging these issues explicitly, during the design process, results in a different understanding of the design professions. Here is a portion of it, heavily edited to make us sound smarter:

0Obviously this depends on one’s definition of ‘effective’ – I’d define it, casually, as an ability to effect certain changes, an ability to act as an agent.

Stephen: Is the effective architect of the future more than a vigilante lobbyist with a penchant for design?0 I’m reading The Infrastructural City right now, which provides an excellent mapping of the current infrastructural condition of LA, its historical development, and some of the consequences. Considered against that background, and what we know about how cities develop, ‘designer’ seems a remarkably inefficient career choice, at least when acting in isolation. Most of the urban projects we would love to see implemented sound a hell of a lot more plausible when pushed by a politician or lobbyist, with some solid PR backing. Can we say that agency isn’t attained through design solutions anymore?

This isn’t just about implementing Landscape Urbanist public works projects, but applies to virtually any work an architect wants to do – which is why architectural tactics (like those Rory and I were discussing above) which challenge typical design-focused boundaries by expanding our understanding of context are so interesting.

Rob: I’m not sure that it was ever any other way. What made Olmsted, for instance, such a formidable figure was that he operated in all these realms simultaneously — design, politics, logisitics, etc. In getting Central Park built (which was, of course, also much the work of his partner, Vaux, though Vaux is much less remembered), he dealt with a highly political competition jury, put pressure on politicans who opposed his vision through the press (such as an article in the Atlantic Monthly), and dealt with both design decisions and logistical problems (in his appointed role as superintendent), all of which is rather fascinatingly recounted in Witold Rybczynski’s biography of Olmsted. Being able to operate in so many realms at once, though, is obviously not something that very many people are going to be able (or want) to do.

Stephen: Right. Which reminds me of an interview (by Jesse Seegers and Jean Choi) with Marc Simmons, of facade consultancy FRONT, in a recent issue of Volume, Content Management (unfortunately not available online). Simmons talks about creative financing measures undertaken to allow the sort of glass within the structural facade they and OMA felt the Seattle Public Library called for, which wasn’t afforded in the budget:

The Seattle Library […] was an unequivocally public project entirely funded by the raising of a public bond. They decided that the building would cost $160 billion [sic – I’m pretty sure he means million]. That’s how much they allocated, and that was what we had as a budget. Our desire to use metal mesh glass wasn’t possible within the budget, so Josh Prince-Ramus and Rem asked for permission to raise funds independently. The client would only provisionally approve that option based on proven support from the Seattle elite, and it’s an interesting idea that a donor can buy the quality of light in a building as opposed to putting his or her name on a room. They were paying for natural light, because otherwise the building would have had dark grey glass and been very different.

Rob: That’s an excellent example of how expanding the role of the architect into another realm (in that case, financing) can make a better project. But no matter how much designers might like to, they can’t control every aspect of a project (and, I should note, Prince-Ramus/Koolhaas weren’t trying to — they made a small, carefully targeted intervention into one particular aspect of the project’s financing in order to obtain a specific architectural result). A lot of historical accident goes into being a designer, too. I’m perfectly comfortable with that, in part because I’m fascinated by historical accidents.

So while in one sense, yes, the role of the designer maybe should get bigger — in that very good work seems to be coming now and probably will continue to come from expanding the context of architecture1 —

Stephen: Or at least, operating on the context to prepare it to accept architecture (if we want to maintain a narrower, more precise definition of architecture).

Rob: — in another sense, I’d like to see designer learn to be happier with smaller roles — more willing to accept that our work exists in a world of accidents outside our control, less determined to control not just the project but the space our projects operate in, because, as ego-boosting as it is to think that being (or being trained as) architects, or landscape architects, or whatever, gives us a peculiarly great understanding of things have value and what things don’t matter, that’s actually an insidious and dangerous way to start to think (though I don’t think architects are any more prone to that kind of thinking than any other set of specialists)2.

2 Which ties into the idea that Geoff Manaugh

frequently repeats (hopefully I’m not mis-representing him): that the use of a building by a janitor, for instance, is every bit as interesting architecturally as the use of a building by a trained design critic.

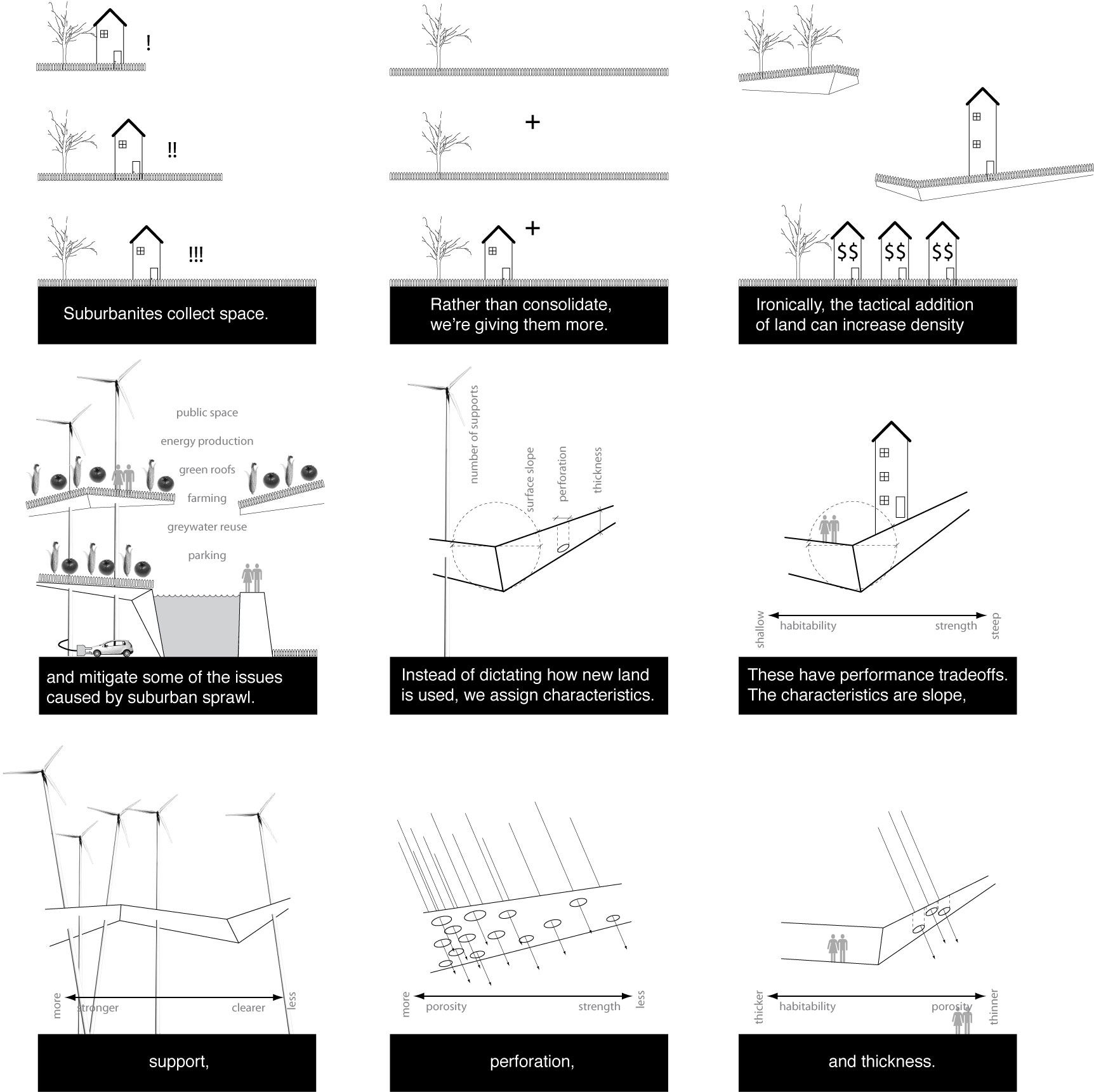

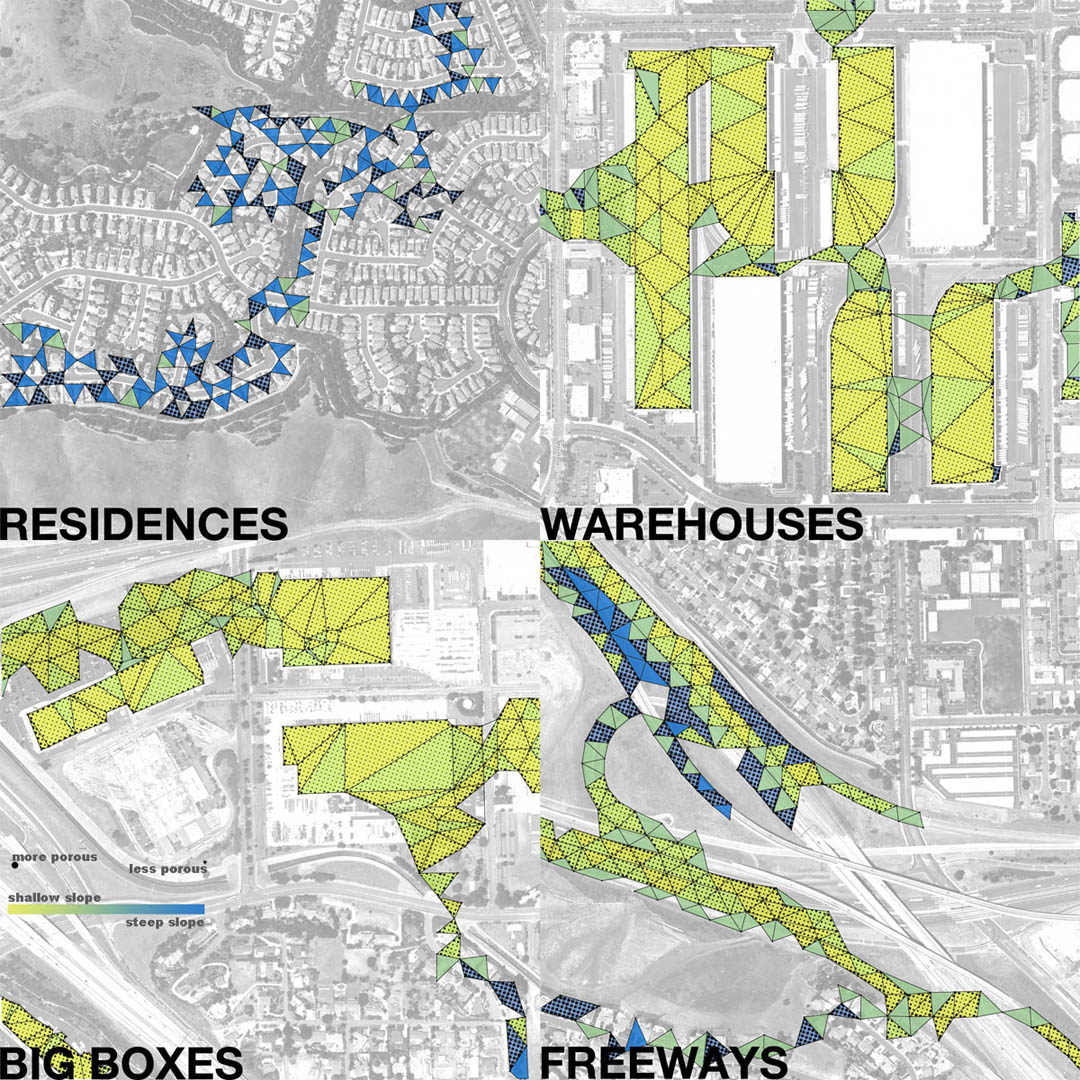

Stephen: To clarify, I’m not arguing that a successful practice necessitates some meta-designer-lobbyist-financier simultaneously managing these intertwined, extraordinarily complex facets of the evolution of a city (or even a single work of architecture) to effect significant, sweeping change. That modernism on steroids would certainly fail. My concern is that the context of architecture in such a complex world does not render architects impotent; that we learn to operate in this networked condition. This will probably involve targeted, incremental projects heavily rooted in an understanding of their existing context, similar to what I noted toward the end of this post. Kazys Varnelis, in The Infrastuctural City, his online writing such as On Informality, and some studio courses, has studied complexity in advanced societies from the perspective of architect and urbanist. A key point is that ‘informality’ is not the savior many believe it to be; that it’s ability to adapt to rapidly changing urban and societal conditions is matched by its inability to engage them in any substantial way. Complexity overwhelms: “even if architects turn toward a radical humility, that doesn’t mean that all of a sudden complex systems somehow unravel themselves. Just as rigidity was the failure point for fordism, complexity is the failure point for post-fordism.” It is simultaneously too humble and too ambitious.

Where does this leave us? In The Infrastructural City, we see the immense complexity of Los Angeles mapped out before us – yet, to the chagrin of the informalists, we also see its ossification. I think we need to go small. Incrementality, while necessarily limited in scope at any single place, has a much greater potential for implementation than does the Landscape Urbanist’s Giant Plan; and provides ample opportunity for re-evaluation over time. Varnelis calls for “an entirely new set of tools” for urban theory – we and others have argued that these tools must include financial and political tactics. This is where an expanded notion of context becomes useful. It’s ironic that Landscape Urbanism initially invested in massive public-works infrastructural projects, but that it’s greatest legacy might be seen in significantly smaller, reduced-scope projects.

Rob: I’m pretty sure that there’s actually no disappointment at all in small victories and incremental change — that their smallness and incrementality is not just a description of the kind of victory that they are, but essential to their positivity.

A rough outline for a narrative history of contemporary urbanism might go like this (note that I’m quite aware that this is vastly oversimplified, but sometimes oversimplification can be helpful, as long as its conscious):

3I’ve found landscape urbanism tremendously interesting, personally, but now I start to wonder if that isn’t because it offered a way to keep Making Giant Plans, even as it offered a critique of modernist planning that suggested that Making Giant Plans is the problem. (An example: Fresh Kills, which is nothing if not A Giant Plan. Actually, I have trouble naming a landscape urbanist project which is not essentially a Giant Plan). Making Giant Plans, though, is inherently appealing, which is why I have a hard time getting away from the desire to do it. An example: the only single-player computer games that really appeal to me have been those that offer the opportunity to remake worlds in both giant swathes and exacting detail — Civilization, SimCity, etc.

1. Architects and planners try to control too much — modernist urbanism, with Pruitt-Igoe as the obvious and notorious example of what that means, and Mike Davis’s Los Angeles or gated suburbia as less obvious but no less notorious examples. Most everyone agrees that this is not positive.

2. The diagnosis is that urbanists didn’t sufficiently understand the complexity of the systems they were operating on.

3. One solution is offered by the Landscape Urbanists3: understand those systems better, accept that they contain some capacity for flux, emphasize process, time, horizontality, and ecology in the design process — but fundamentally (particularly in the case of AALU, which is admittedly a special case and somewhat distinct from the North American/Australian strands of Landscape Urbanism), still seek to affect goals at a very broad level within the city (seek fundamental change).

4. This is problematic, though, for reasons such as the inertia of the urban system or the impossibility of achieving adequate understanding of the forces acting on a given project within the timeframe available to the designer.

4 An alternate (and, in my opinion, scary) path would be the alignment of architecture and autocracy, for reasons similar to those Tom Friedman gave in his

op-ed pining for an American autocracy — the authority to get. things. done.

5. One possible solution, then4: hack small things, instigate small changes and watch them develop. Alter your tactics or continue to implement, as you see results unfold. Maybe this even suggests that the study of landscape/architecture ought to be re-understood — as an inculcation into a way of thinking with a very broad and loosely-defined set of applications, rather than apprenticeship in a particular set of skills (and, yes, I’m aware that there’s a potential conflict between asserting that designers don’t have a “peculiarly great understanding” and that greatest value of a design education might be the development of a way of thinking, but I think the two can be reconciled).