Pruned asks: “Has there ever been an ideas competition of any kind for Mexico City and its water crisis?”, in response to this post at the Guardian outlining that crisis. While I’m not aware of a competition, the unrealized project that immediately comes to mind is Kalach and de Leon’s The City and the Lakes, which I first read about in Megan Miller’s article “In the Nature of the Valley”, published in Praxis: Mexico City. Unattributed quotes in the following piece are from that article. I don’t use twitter (poll: should I? Now that I’m blogging something I read on twitter, maybe I have to reevalute my distaste for twitter), so I’m blogging this.

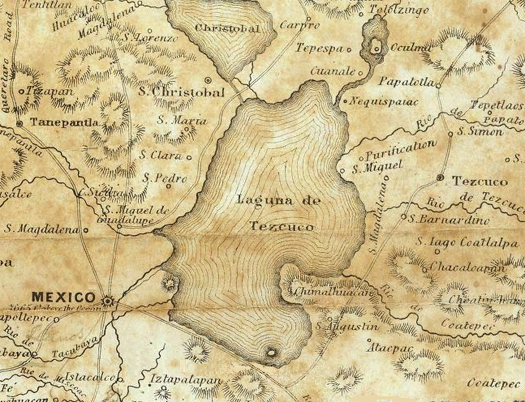

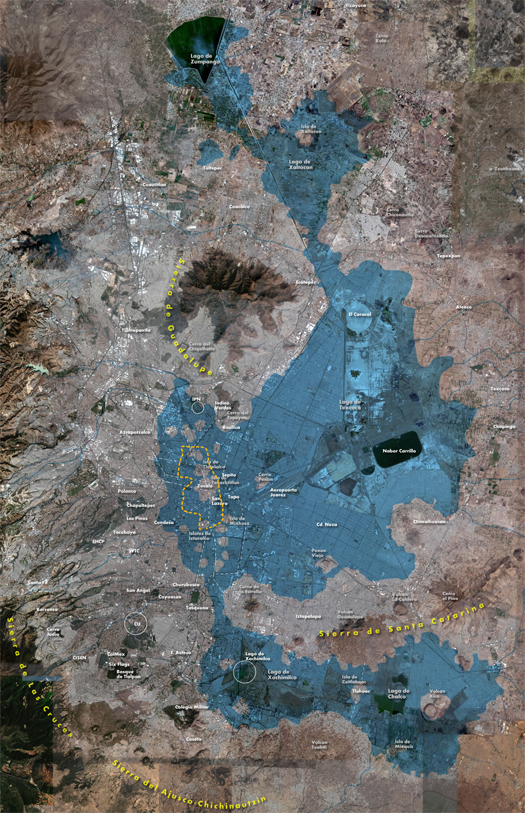

In 1998, Mexican architect Alberto Kalach and his colleague Teodoro Gonzalez de Leon published La Ciudad y sus Lagos, a bold proposal that examined the potential resurrection of Lake Texcoco, the largest of the lakes which Mexico City’s predecessor Tenochtitilan was founded on. The revitalization of the lake would serve to both benefit Mexico City ecologically and to invigorate the practice of urbanism in Mexico.

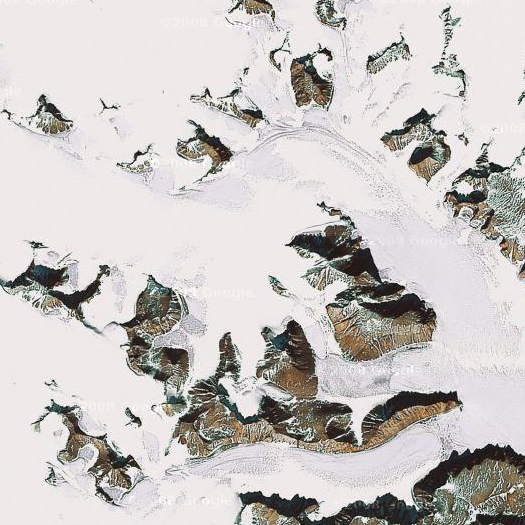

The idea behind the Lakes Project descends from a report written by a soils expert and professor, Nabor Carillo, in the 1960s. Carillo held that the centuries of attempts to drain the lakes of Mexico City (intiated by the Spaniards shortly after conquering Tenochtitilan) were in error. Those centuries of efforts — perhaps most impressively represented by the 1789 completion of the Nochistongo ravine and the networks of canals such as Huehuetoca — had left Mexico City lying below the phreatic level (the natural surface of the static water table) and consequently in constant state of war with floodwaters. Carillo’s program was radical because, rather than continuing and expanding efforts to funnel water away from the city, he suggested “reconstructing the city’s original lakes as natural detention ponds for controlled flooding and containment of treated wastewater”.

Unfortunately, Carillo’s proposal was, in addition to being rather ahead of its time in seeing stormwater and wastewater as resources rather than problems, rather ignored. Mexico City pressed ahead with the construction of the Drenaje Profundo, a network of sixty miles of deep underground drainage tunnels, which were completed in the 1970s and ominously dubbed the “final solution”. Until Kalach and Gonzalez de Leon dusted off Carillo’s work to inspire their own, Carillo’s primary and somewhat ironic legacy was that the artificially-sustained shallow pool of water that is all that remains of Lago Texcoco has been named Lago Nabor Carillo.

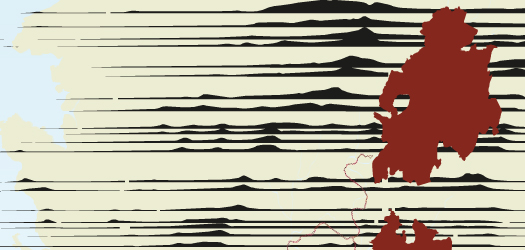

Kalach and Gonzalez de Leon adopted Carillo’s suggestion, but developed it further. Their proposal reorganizes the Drenaje Profundo into a recycling system that recharges Mexico City’s aquifers, rather than conveying water away to the Gulf Mexico, as the current system does. The proposed system would recharge the aquifer with filtration from rain as well as treated wastewater collected in new lakes, adding moisture to Mexico City’s notoriously polluted air and ameliorating water supply and soil subsidence problems that currently plague the city. Vegetated ravines would be preserved on the perimeter of the lake, providing for the cleansing of stormwater and rainfall making its way down the slopes into Texcoco.

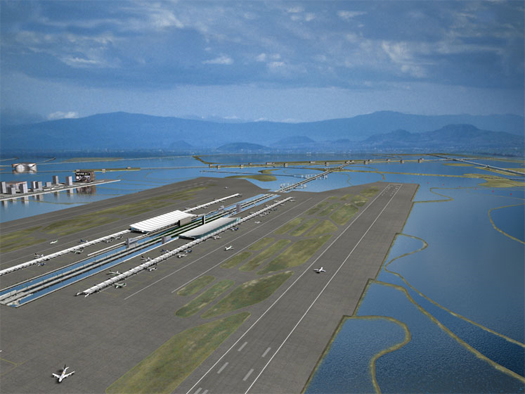

The revitalized Lake Texcoco would be the largest of the new lakes (just as it was once the largest lake in the valley). From its position on the periphery of Mexico City’s rampant, disorganized growth, the lake would serve as a powerful ordering mechanism, redirecting growth to its edges. It would also provide “a literal and operational platform for new transportation infrastructure, including expressways, transit lines, and a much needed new airport”. Kalach explains the urban potential of the project:

“We are proposing a new airport on an island in the Texcoco Lake, twenty-two kilometers from the historic center. This would function as the new entrance to the city. The proposed airport and associated rapid-transit systems would stimulate urban growth on the low hills to the east of the city, which an area well-suited for urbanization. Concurrently, growth would be slowed on the shores of the lake and on the forested side to the west, which is now an area for the natural recharge of the aquifers. The project really functions at two scales. At the metropolitan level it deals with access roads and the airport. At the local level it addresses the area around the lake, revitalizing the low-income settlements that are currently there. In this way the larger project would foster both a local and metropolitan connection between the city and its lake”.

The Lakes Project exemplifies the potential for the design of infrastructures to function on two levels, the first of which would be the immediate functional potential of the infrastructure (the thing which the infrastructure enables) and the second of which would be the potential for the infrastructure of affect the growth of the urban entity it is embedded in (the infrastructure’s potential to generate the city). Kalach’s proposal treats the enabling function of the regenerated Lago Texcoco (its ecological and hydrological function) equally with its potential to generate a more positive urbanism for Mexico City. Moreover, though Kalach claims the project develops out of geography, not history (a claim which might be criticized for creating a dichotomy between two intimately intertwinned ways of understanding), the poetic impact of rebuilding a piece of Tenochtitilan within Mexico City’s limits is not difficult to discern. As Kalach states:

“I have always felt that Mexico City somehow lost its reason for being. The city had been founded here for specific reasons, but no longer responded to its origin. It seemed that, through the Lakes Project, the basin could recuperate its lacustrine character, and life and sense could be returned to a place that had lost its form or transformed itself to the extreme”.