The following piece is a guest post from Peter Nunns. Peter is a recent graduate of the University of Auckland, with a MA in Political Science; mammoth readers may be familiar with him from his contributions to last summer’s discussion of the Infrastructural City. His current research interests include shelter and urban development challenges in developing-world cities, the rescaling of political economies, and the reconstitution of citizenship rights within the city. Peter hails from California, but now lives in his ancestral homeland of New Zealand.

The filmmaker Prahlad Kakkar, the auteur of the toilet documentary Bumbay, told a startled interviewer that in Bombay “half the population doesn’t have a toilet to shit in, so they shit outside. That’s five million people. If they shit half a kilo each, that’s two and a half million kilos of shit each morning.” (Mike Davis, Planet of Slums: 142)

In India, where distance from one’s own excrement can be seen as the virtual marker of class distinction, the poor, for too long having lived literally in their own shit, are finding ways to place some distance between their waste and themselves. The toilet exhibitions are a transgressive display of this fecal politics… (Appadurai, Arjun, “Deep Democracy: Urban Governmentality and the Horizon of Politics” in Public Culture: 39)

1 cf. Mike Davis’s Planet of Slums (2006)

2 UNDESA 2008, 2009

“Slum” is a word with a weighty and questionable history, but in the last decade it has been “operationalized” into a small set of criteria by housing agency UN-Habitat. Although it has become commonplace to talk of “a billion slum-dwellers” globally1 , it would be more accurate to discuss the infrastructural and legal shortcomings of developing-world cities. For example, in 2010 the UN’s Global Urban Observatory estimated that 185 million Indians, or 50.7 percent of the country’s urban population, lived in slum conditions2. Actual living situations are highly diverse, ranging from Kolkata’s pavement-dwellers to Mumbai’s chawls, or run-down former factory housing, but one thing that most slums have in common is a profusion of shit.

3 World Bank 2011

4 Burra, Patel and Kerr 2003

According to the World Bank, in 2008 46 percent of Indian urbanites – or nine out of every ten living in a slum – lacked “improved sanitation facilities”, meaning that people living within them lack sewerage and public toilets3. Where community toilets do exist, poor maintenance and overuse often render them unsanitary before long. For example, a survey of 151 slum settlements in Mumbai conducted by Mahila Milan/NSDF found that there were 3,433 municipal toilet seats, 80 percent of which were not working, to serve one million people – a ratio of one toilet for every 1,488 people4. Likewise, a 1993 survey of half a million slum-dwellers in Kanpur found that 66 percent had no toilets. Lacking facilities, they shit in the open or in waterways.

5 Appadurai 2002: 39

6 Davis 2006, Burra, Patel and Kerr 2003, Bapat and Agarwal 2003

As a result, residents of slums face a disproportionately high disease burden, with high incidences of cholera and diarrhea. “One macabre joke among Mumbai’s urban poor is that they are the only ones in the city who cannot afford to get diarrhea. Lines at the few existing public toilets are often so long that the wait is an hour or more, and of course medical facilities for stemming the condition are also hard to find”5. But in addition to being a public health crisis, the lack of sanitation is especially concerning for women, who are most severely affected by the lack of privacy when defecating6. In public toilets, they are frequently harassed. Defecating in the open in the absence of toilets is even more risky; as a result, most women choose to do so at night or in the early hours of the morning, which in turn leads to gastric disorders.

7 UNDESA 2010

8 Burra, Patel and Kerr 2003: 20

9 McFarlane 2008: 102

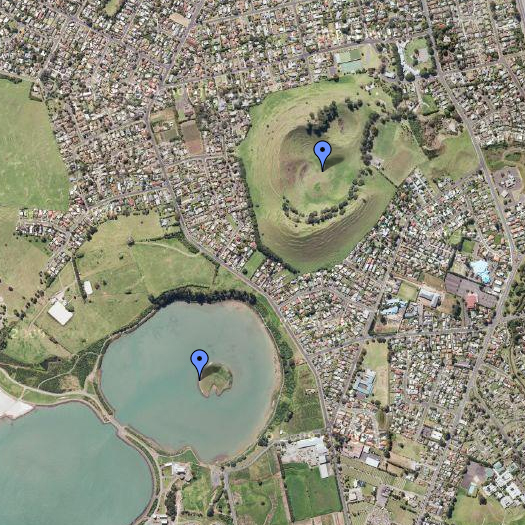

There is no obvious solution to this particular infrastructural shortcoming. Because many slum settlements are illegal or informal, occupying the margins of railway lines and airports and other undeveloped land, city governments are not keen to extend sewers and other utilities into them. Funding and building public toilets is often problematic for the same reason. When the Indian government allocated money for toilet block construction in the 1990s, most of it went unspent due to city governments’ disinterest in upgrading slums. In Pune (population: 4.4. million in 20057), a municipal initiative resulted in the construction of only 22 toilet blocks between 1992 and 19998. The toilets that were built often became unusable relatively quickly due to overuse and a lack of maintenance or cleaning. Even in cases where projects were completed and maintained, the “focus on cost recovery from the poor means that sanitation is often provided not according to those who need it most, but according to how many people can pay a contribution”9.

10 Burra, Patel and Kerr 2003: 19

11 Burra, Patel and Kerr 2003: 20

I’d argue that sanitation in Indian cities is not just a challenge for urban planning and architecture; it’s also an essentially political problem. One of the most successful programs of community toilet construction involved not just new design elements but the development of what Arjun Appadurai describes as “fecal politics”. After the failure of Pune’s city government to deliver toilets, its municipal commissioner invited NGOs to bid for construction and maintenance contracts. A national shelter activist group, the Alliance between the Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC), the National Slum-Dwellers Federation (NSDF), and Mahila Milan (or “Women Together” in Hindi), won a contract to build 320 toilet blocks with 6,400 seats throughout the city10. As a result, “between 1999 and 2001, more toilets were constructed and more money spent than in the previous 30 years”11. Equally important, the new toilets were designed and constructed by those living in the slums, resulting in lower building costs and several important architectural innovations.

12 See Appadurai 2002, Patel and Mitlin 2001, Patel, Burra and D’Cruz 2001

The Alliance’s success in sanitation is a result of its particular model of political activism, which is rooted in the everyday experience of slum-dwellers but diffused among national and global networks. Its “politics of shit,” tested in Pune and subsequently replicated in Mumbai and other cities, is a response to the infrastructural and legal dilemmas facing its members. Others have written at greater length on the organization and operation of the Alliance12. Rather than duplicating all of their work, I’d like to discuss its technique of employing the knowledge and expertise of the urban poor.

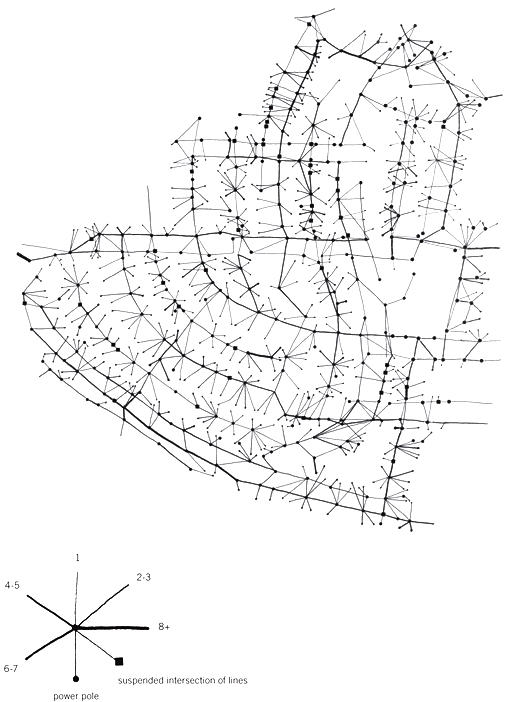

Fecal politics relies upon information generated by and for slum-dwellers, testing and legitimizing new or existing uses of urban space. Appadurai describes it as “a politics of show-and-tell”, in which slum-dwellers “claim, refine, and define certain ways of doing things in spaces they already control and then use these practices to show donors, city officials, and other activists that their ‘precedents’ are good ones and encourage such actors to invest further in them.” The Alliance’s projects invariably employ community knowledge of the daily challenges of slum living – particularly in terms of housing quality and access to water and sanitation – to devise ways of improving their lives. As Burra, Patel, and Kerr note, this is appropriate given that slum-dwellers are the people who actually build cities:

People are the best experts. A long-established myth is that experts with advanced degrees are needed to plan improvements in slums. But the realities of life in India’s slums are best understood by slum dwellers themselves. If experts had a better track record, their expertise might have more credibility – but the deplorable state of infrastructure in Kanpur or Bangalore suggests there are serious holes in this “expertise”. The slums in India are home for most of those who actually build cities: masons, pipe layers, cement mixers, brick carriers, shuttering designers, stone cutters, trench diggers and metal fabricators. The poor, as they construct their own homes and neighbourhoods, are already the designers and implementers of India’s most far-reaching systems of housing and service delivery. The systems they use are not ideal, are largely “illegal”, and often inequitable, but they reach down to the poorest groups and cover far more ground and affect far more lives than any government programme could ever achieve.

Quite often, the “people” Burra et al are referring to are women. Although women still face a number of structural barriers to participation in the public sphere, as suggested by their low rate of labor force participation (in 2009, 81.1 percent of men were in the workforce, compared with only 32.8 percent of women), they are often the most knowledgeable about living conditions in slums. Most women in urban India labor in the home, performing unpaid domestic work or various types of subcontracted homework, and they are most heavily affected by the lack of water and sewerage. As a result, women play an important role within the Alliance: they are strongly represented in its leadership and are responsible for much of the financial side of slum upgrading through Mahila Milan’s savings collectives.

13 Burra, Patel and Kerr 2003: 11

14 Appadurai 2002: 41

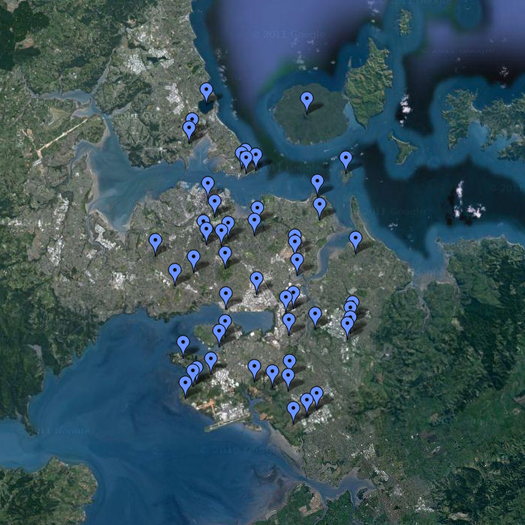

The politics of shit is, of course, an intrinsically local thing. What could be more intimate, more deeply particular to an individual place, than defecation? But at the same time, the lack of toilets and sewers is a problem shared by most slum communities, irrespective of their own particularities. As a consequence, the Alliance’s work tends to cross geographic scales: it integrates local struggles into national (the 750,000 members of NSDF across 52 Indian cities13) and international (Slum/Shack Dwellers International (SDI), a federation of shelter groups from Latin America, Africa and Asia14) networks. This gives the Alliance scope to scale up projects and precedents that have proven successful at a local level. This process facilitates “horizontal learning” through the exchange of slum upgrading methods, critical debate, and solidarity among shelter activists and slum-dwellers.

15 Patel 1999a: 11-12, Burra, Patel and Kerr 2003: 15

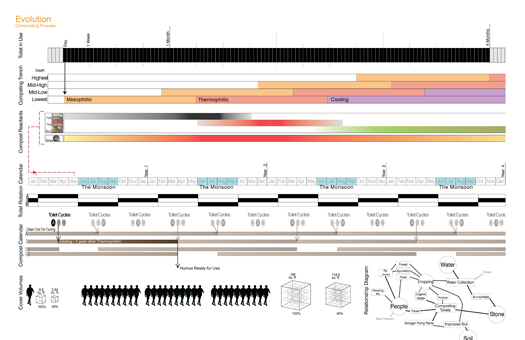

Practicing fecal politics has delivered concrete gains for Indian slum-dwellers. In Pune, the Alliance ultimately constructed 400 toilet blocks with roughly 20 seats apiece, which are capable of serving roughly half a million people a day provided that they are kept clean. They were designed, built, and managed by community members, those who “actually build cities”, rather than by outside contractors as is normal for such projects. In doing so, Pune’s slum-dwellers were able to draw not just upon their own experiences but on knowledge developed within the Alliance as a result of smaller-scale projects carried out in Mumbai, Kanpur, Bangalore between 1988 and 1996 with funding from the UK charity Homeless International and from slum-dwellers themselves15.

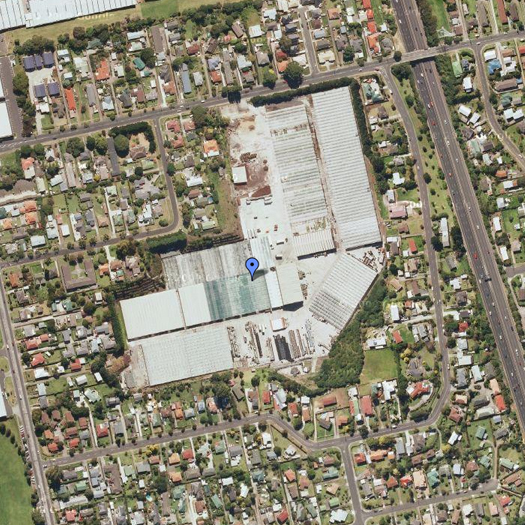

“Photo 1: Aundh toilet block built by the community in Bangalore.Credit: Photo provided by the UK charity, Homeless International”; from Burra, Patel and Kerr (2003)

16 Burra, Patel and Kerr 2003: 22, see also Burra and Patel 2002, Bapat and Agarwal 2003

The result was better toilet facilities constructed at a lower cost – 5 percent under municipal cost estimates, according to Burra and Patel. Design innovations made them well-lit, better-ventilated and easier to clean, important considerations given that public toilets in Indian cities have a history of becoming rapidly fouled. For example, storage tanks were increased in size to ensure that there was sufficient water for washing up and keeping facilities clean. Input from women, who are particularly vulnerable to the lack of appropriate toilet facilities, resulted in several simple but important new features. Toilet blocks were designed to reduce harassment by including separate entrances for men and women, and seats that did not directly face each other. And, recognizing that children are generally shunted aside in latrine queues, blocks of children’s toilets were also constructed. As the picture below shows, these were specifically designed to be easy for children to use, with handles, smaller openings, and child-friendly decorations16.

17 Appadurai 2002: 39, Burra, Patel and Kerr 2003: 24-25

The Alliance recognized from the start that constructing a toilet isn’t sufficient to improve sanitation in the slums, as they must be cleaned and maintained in order to be usable. Collecting the money to do so is challenging, as it must balance usability with accessibility. “User-pays” fees for public toilets are unaffordable for many residents. They are usually set at one rupee per month – a small amount that adds up quite rapidly. Families living at the official urban poverty line of 20 rupees per person per day would strain to pay even that. Consequently, the Alliance has relied upon community organization and a system of affordable collective payments from slum households – roughly 20 rupees per month – to pay for maintenance17. In order to hold maintenance costs down, caretakers and their families are provided with a room in toilet blocks as part of their compensation.

18 Appadurai 2002: 39

19 Satterthwaite, McGranahan and Mitlin 2005: 5

20 Burra 2005: 84

In keeping with its principles, the Alliance has actively shared the knowledge it has developed, both within its own network and with other interested groups. Communities have put on “toilet festivals” to celebrate and publicize their new facilities, thereby reinventing “this private act of humiliation and suffering as the scene of technical innovation, collective celebration, and carnivalesque play with officials from the state, the World Bank, and middle-class officialdom in general”18. This has helped to stimulate interest in community-built and -maintained toilet blocks among city governments, other NGOs and CBOs, and the World Bank. As a result, Pune’s toilets have set a precedent for future sanitation improvements in Indian slums. For example, in 2000 the World Bank and the Mumbai Municipal Corporation funded the Alliance to construct 320 similar toilet blocks in that city19. In 2001, the Alliance’s successes in Pune and Mumbai encouraged the national government to provide subsidies for similar public toilet construction programs20.

There are many more things that could – and should – be said on fecal politics. I’ve hinted at a few of them here. Obviously, there is a lot more to say about the architectural practice that it might generate. But speaking for a moment as a political scientist, what I find fascinating about the work of the Alliance is the way that it alters the meaning of citizenship. If the politics of shit is a way for slum-dwellers to “place some distance between their waste and themselves” – both literally and figuratively – it is also a way for them to claim the right to live in the city. When Bapat and Agarwal interviewed slum-dwellers in Pune and Mumbai about water and sanitation issues, a recurring complaint was about their own invisibility to politicians and planners. By building their own toilets, and then showing them off in toilet festivals, they reclaim some of the legitimacy denied to them by governments.

Click through for references and tables.

Read More »