This is week seven of our reading of The Infrastructural City; if you’re not familiar with the series, you can start here and catch up here. With our delayed posting of the previous chapter, we didn’t get around to posting an index, but you can read FASLANYC’s contrarian take on the chapter here and Peter Nunns’ look at telecoms, the future of air travel, and de-globalization here.

[Powerline pruning, photographed by flickr user Justin Berger]

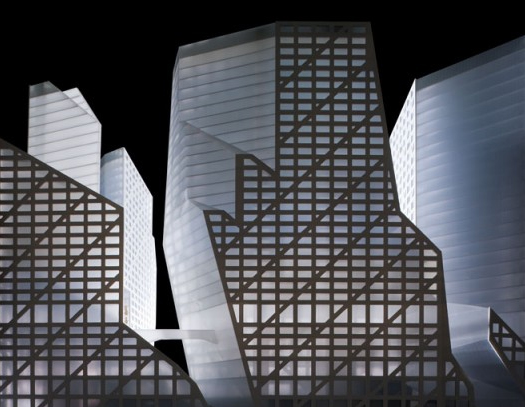

In the seventh chapter of The Infrastructural City, “Landscape: Tree Huggers”, architect Warren Techentin discusses “landscape as a foundational infrastructure” in Los Angeles. (By landscape, it’s worth noting, Techentin means specifically ‘plants’, usually ‘trees’, and quite often ‘cultivated trees’, though “accidentally imported” plants make the occasional appearance, as well.)

Techentin begins by describing the initial entanglements of Los Angeles with trees: the council tree near which the Gabrielino Indians built the village of Yangna, Los Angeles’ immediate predecessor; the orange groves, which brought both economic vitality and the ever-increasing demand for imported water to the basin; and, most recently, imported ornamental trees.

The most iconic of these imported trees, the palm, was particularly vital in constructing the image of Los Angeles. Real estate developers — such as Venice Beach’s Abbot Kinney — planted rows of them to demarcate plots, botanical markers of future urbanisms. The palm was particularly valued for its exotic effect, which suggested to the prospective resident that Los Angeles was not just a place of economic opportunity, but a paradise of tropical (or, at the very least, Mediterranean) leisure.

LANDSCAPING

[Landscaping, idealized and extreme; photographed by flickr user Anna Verlet]

The palm, though, is only one early tool in the kit of plants used to alter the image of the city, a kit which has been refined and expanded as Los Angeles developed its extensive and signature car culture.

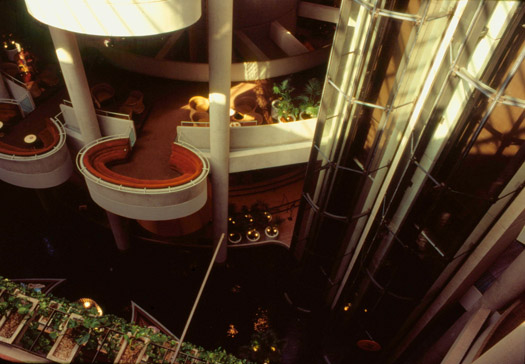

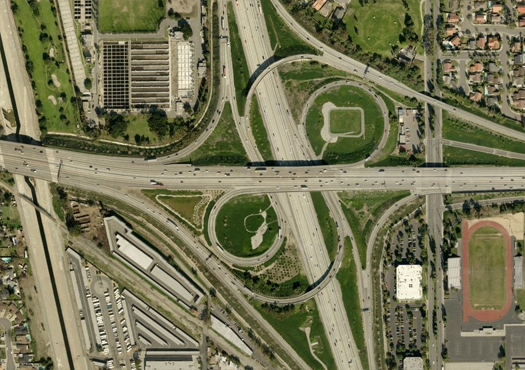

“After people moved in, so did businesses, and trees and plants were again used to raise the value of commercial properties. The front doors of many businesses in Los Angeles are accessed through parking lots so the effective use of landscaping to provide relief from the acres of asphalt is important for business. In a city built around cars, new forms of landscaping comprised of edging, hedging, containment, concealment, signage, embankment, topiary, and decor emerged simultaneously with the developing car culture. When the pedestrian space of the sidewalk disappeared amidst the spaces of strip malls and parking lots emerged between the street and the building, landscape again helped to soften the deleterious effects of the quickly erected, often bland commercial architecture. Particularly at fast food restaurants, new concepts of landscape were deployed exuberantly, often monstrously, to enhance the meal. Images of the pastoral suburban landscape of the Garden City, the exotic landscapes of Eden, and the topiary gardens of France and Japan were marshalled to screen the growing proliferation of urban artifacts: trash cans, electrical transformers, water meters, building edges, air conditioning condensers, and the sidewalk or roadway itself. All of these objects disappear through carefully selected plantings, thus allowing patrons to enjoy an authentic indoor-outdoor eating experience a few feet away from their automobiles. At any drive-through of a fast food restaurant, a country road is evoked as drivers circle their way between the speaker and pick-up window amidst plants that beautify the wait for food with a pleasing, planted environment that has grown over the stains, graffiti, garbage, insects, and dust of the city”

Landscaping — distinguished from other cultivated landscapes and gardens by its ubiquitous presence and banal qualities — is landscape as a real estate amenity. This is the landscaped iteration of the ‘equity urbanism’ that we described in our essay, “The Shelter Category”, that was published in MONU #12:

“…ownership culture [and ‘equity urbanism’ are] ultimately not founded on the rationales of personal responsibility, security, or stability, but upon the notion that the home is an asset for the cultivation of personal wealth. Architecturally, this is a strange notion —the home as a wealth generator, not shelter – but it does a great deal to explain the dominance of the primary architectural forms of contemporary America, the cheaply built urban condo and the even more cheaply built suburban home. The notable thing about both these architectural forms is how un-engaged architects are with them: both in that most critical discourse is unconcerned with mass-produced housing and in that mass-produced housing is produced with very little input from architects.”

Like architects who are essentially un-engaged with mass-produced housing, landscape architects are essentially un-engaged with car culture landscapes, even though, as many critics have noted, landscape is the primary medium constituting the automotive city. (We, at least in my experience, tend to shrink from the suggestion that there is any connection between what a ‘landscaper’ does and what a ‘landscape architect’ does.)

Techentin notes, though, that the palms are dying — many of old age, some of fungal and other diseases. The city, eager to replace these exotic trees with native species, has no plans to import replacements, indicating, to Techentin, that the era of landscape as image in Los Angeles is ending (though, it should be said, there is no apparent end in sight for landscaping as a mass amenity, and part of the reason that the city is not replacing palms is that their use in luxury developments in Florida and the southwest has driven up prices).

PERFORMATIVE URBAN FORESTS

[Mullein — Verbascum thapsussm — via Peter del Tredici]

The question we are left with, then, is: what are future urban natures like? Techentin argues that, as the palms die out — and, with them, perhaps also the idea that the landscape exists primarily to create an image — urban forests will become performative:

“While the city may be in the process of abandoning the palm as its foremost icon, trees continue to be enlisted as supplements to urban life… This relationship has become more symbiotic as we have come to an understanding of the importance of trees in the urban ecosystem. Taken in conjunction with plant life everywhere, trees collectively function like a giant machine — an enormous oxygen-producing and pollutant filtering infrastructure for the city. Urban forests generate oxygen, absorb airborne and ground toxins, beautify, shade, create privacy, reduce water run-off into storm systems, stabilize soil to prevent erosion, mitigate reflected heat off roads and sidewalks, produce “curb appeal” thereby increasing real estate values, provide wind control, animal habitat, and a source of food and flowers.”

“If, however, trees in the city have traditionally been appreciated because they were useless — removed from their non-urban cousins, which exist to provide us with lumber and fuel — they are increasingly becoming machines, bits of living infrastructure. The fall of the palm — that vapid, high-maintenance Hollywood starlet — is tied to this idea of trees moving from being merely ornamental to more performative organic machines — walling us in, generating the air we breath, shading our cities.”

One possible way in which forests might become performative, suggested by Techentin, is that they may be “hybrid mechanic-organic systems”:

“With the Frankenpine [cell phone towers which mimic tree forms] thriving, it is possible to speculate on an urban future in which thousands of artificial trees might be deployed throughout the city: on streets, in malls, and in our office landscapes. In the next generation of office or mall equipment, we may see new tree-machines proliferating amongst this landscape–providing wireless communication, video monitoring, air filtration, security, and space for storage, digital or otherwise. One can imagine a whole forest of imitative, performative, and embedded artificial “trees” deployed amongst real trees or, for that matter, prosthetic systems that would augment living trees, providing necessary features that we otherwise would find disagreeable to look at, some of which may provide a solution for some of today’s urban ills such as the reintroduction of animal habitats, methane gas venting, hazmat, and security monitoring systems, and so on.”

This, I suppose, might seem far-fetched and a stretching of the ‘tree’ metaphor until it becomes very thin indeed, but I’m not so sure that it is entirely ridiculous. What are these carbon storage structures, if not cybernetic trees (the engineers even refer to them as “artificial trees” configured in a “forest”), and what are the Voltrees (elaborated upon here by Pruned), if not prosthetic trees?

[Fall Panicum grows in pavement, via Peter del Tredici]

But, I would add (and this seems much more important to me): the rise of the performative tree will also be seen in the acceptance and valuation of “crypto-forests”, “cosmopolitan” plant communities, and invasive species. Techentin says: “Wild nature, or what may be left of it, seems all but removed from collective experience.” Despite this collective remove, though, there is wild nature in the city, only it is invasive and post-human, growing in legal and physical spaces of abandonment: a fence on property line, a sliver of land between two properties deemed to have no value as real-estate, the concrete bed of a channelized river.

I’m reminded of the fantastic new field guide, Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast, which is written by Peter del Tredici, who is both a botanist and researcher at the Arnold Arboretum and a lecturer for Harvard’s landscape program. Wild Urban Plants, though it is first and foremost a guide to the identification and characteristics of what del Tredici calls “cosmopolitan plants” — those plants which are adapted to the contaminated soils, frequent disturbance regimes, and harsh growing conditions which characterize urban ecologies, and so are able to survive and even thrive without maintenance or care in cities — is also an opportunity for del Tredici to make the argument that we ought to begin to value these plants (many of whom are often lumped together under the derogatory rubric of “invasives”) and the communities that they form, because they provide ecological services at a uniquely low cost.

Quoting at length from del Tredici’s recent article in Natural History (PDF):

“The ecology of the city is defined not only by the cultivated plants that require maintenance and the protected remnants of natural landscapes, but also by the spontaneous vegetation that dominates the neglected interstices. Greenery fills the vacant spaces between our roads, homes, and businesses; lines ditches and chain-link fences; sprouts in sidewalk cracks and atop neglected rooftops. Some of those plants, such as box elder, quaking aspen, and riverside grape, are native species present before humans drastically altered the land. Others were brought in intentionally or unintentionally by people, including chicory, Norway spruce, and Japanese knotweed. And still others, among them common ragweed, path rush ( Juncus tenuis), and tufted lovegrass (Eragrostis pectinacea), arrived on their own, dispersed by wind, water, or wild animals. Such species grow and reproduce in many American cities, especially cities with faltering economies, without being planted or cared for. They can provide important social and ecological services at very little cost to taxpayers, and if left undisturbed long enough they may even develop into woodlands.

There is no denying that most people consider many such plants to be “weeds.” From a utilitarian perspective, a weed is any plant that grows on its own where people do not want it to grow. From the biological perspective, weeds are opportunistic plants that are adapted to disturbance in all its myriad forms, from bulldozers to acid rain. Their pervasiveness in the urban environment is simply a reflection of the continual disruption that characterizes that habitat—they are not its cause. [Emphasis mine.] …

In general, the successful urban plant needs to be flexible in all aspects of its life history, from seed germination through flowering and fruiting; opportunistic in its ability to take advantage of locally abundant resources that may be available for only a short time; and tolerant of the stressful growing conditions caused by an abundance of pavement and a paucity of soil. The plants that grow in our cities are a cosmopolitan array of species that somehow managed to survive the transition from one land use to another as cities developed. The sequence starts with native species adapted to ecological conditions before the city was built. Those are followed, more or less in sequence, by species adapted to agriculture and pasturage, to pavement and compacted soil, to lawns and landscapes, to infrastructure edges and environmental pollution—and ultimately to vacant lots and rubble…

Based on the extensive literature on the ecosystem services provided by native and cultivated plants, one can easily generate an impressive list of the ways spontaneous vegetation makes cities more habitable for people as well as animals: temperature reduction, food and habitat for wildlife, erosion control on slopes, stream and riverbank stabilization, excess nutrient absorption in wetlands, soil building on degraded land, improved air quality, noise reduction, and, of course, carbon sequestration.”

Notably, that list of ecosystem services is virtually identical to that Techentin recites for ‘landscape’ in general. This does not mean that every ‘invasive’ plant needs to be welcomed in every context, of course, but it does suggest, as mammoth has argued before, that this derogatory classification can prevent us from rationally weighing the relative ecological merits of species.

LANDSCAPING AS INFRASTRUCTURE

[CMG Landscape Architecture’s “Crack Garden” — unfortunately planted rather than spontaneous, but you get the idea.]

Each of these possibilities involves a common element: the expansion of the agency of the landscape architect. (Expansion, though, should not be an egotistical moment, but an opportunity to engage in new forms of collaboration.)

Those two primary possibilities (the rise of the performative urban forest and the engagement of landscape architects in the design of ‘banal’ landscaping) might even merge, not in landscape infrastructures, but in landscaping as infrastructure. To borrow the terminology of Stephen’s previous post: landscaping is currently culturally and financially performative, but it could become ecologically and infrastructurally performative. (To do so, though, may involve difficult re-framings of the cultural expectations it performs for.) This, I think, begins with prosaic shifts like the introduction of curb-side rain gardens or front lawns that are variously xeriscaped and edible, but I don’t think it can end there.

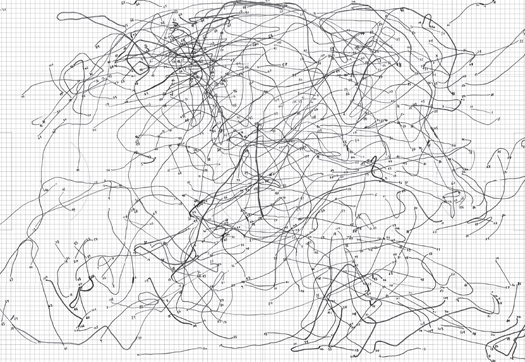

I also suspect that, if landscape architects are involved in such a change, it will require assuming a somewhat different set of roles and design methodologies than those we have traditionally employed: there may be some amount of employment to be found in designing edible estates and cosmopolitan succession regimes for a mass market, but first that mass market must be persuaded of the value of such landscapes.

The need for such persuasion — a change in what might be termed vernacular landscape norms — reminds me of an article in the April issue of Metropolis, which described the recent work of Build Change, a non-profit organization that works in areas affected by earthquakes to help locals build in ways that are more seismically sound. “Careful seismic engineering”, author Karrie Jacobs notes, “can be broken down into simple rules that can be followed at relatively low cost”. In Haiti, Build Change designed sample housing plans and built a pilot house that meet those criteria using local materials and building techniques, but — most interestingly for our discussion of landscaping norms — “also distilled their design into ‘six simple rules’, which appeared on posters as dos and don’ts”:

“… at least 6,000 homes in Indonesia and China [which Build Change worked in after earlier earthquakes]… have been built following the rules developed… What [Build Change] does is exactly the opposite of an architectural competition. It’s not about coming up with a signature solution but disseminating a set of rules that if truly effective, disappear into the venacular.”

The posters that Jacobs describes are a fascinating architectural act. Architecture, here, is not a building, but a viral meme, infecting the genetic code of a country’s building practices. This, obviously, is relatively necessary and efficacious after a disaster, when the traditional practices of architecture may be ineffective, too expensive, and too slow, but it also suggests something about how landscape architects might look to induce a shift towards ecologically and infrastructurally performative landscaping. The employment of such alternative practices — I’m thinking of a landscape-centered design advocacy organization, for instance, akin to the Center for Urban Pedagogy, publishing pamphlets of landscape tactics akin CUP’s Making Policy Public series — may yet offer the opportunity to influence the future forests of the infrastructural city.