This is week five of our reading of The Infrastructural City; if you’re not familiar with the series, you can start here and catch up here.

[Traffic cameras in Los Angeles, photographed by flickr user Puck90]

“Blocking All Lanes”, Sean Dockray, Fiona Whitton, and Steve Rowell’s contribution to The Infrastructral City, opens by questioning the various meanings of “traffic”:

“If Los Angeles evokes sunshine, flashy cars, and movie stars, it also instantly brings to mind traffic. But the word “traffic” is always a little slippery, one of those words that escapes us when we try to pin it down. For engineers and the dictionary alike, “traffic” refers to the movement of vehicles along a roadway. For the rest of us, however, traffic has come to mean the exact opposite: that phenomenon of vehicles crowding a roadway until everything slows down to a frustrating crawl…

…We are traffic… Of course, we don’t talk that way: we say that we are “in traffic”, but we never admit to being traffic… our need to remove our own culpability from congestion, our need to speak of being “stuck in a jam”, is an expression of our profound ambivalence to driving. The automobile, the capitalist vehicle par excellence, promises freedom while the often-frustrating experience of driving leaves us feeling quite out of control. We hold onto the idea that although we might be stuck now, there is a way out. But what if our agency were underpinned by an organizing, computational mechanism? We stop. We go. We turn. We yield. What if these were not simply rules to follow (code as law), but instructions to follow (code as program)…”

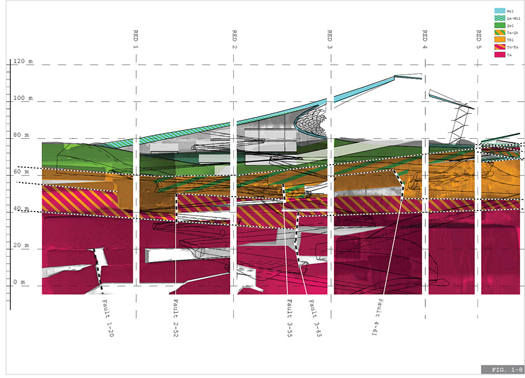

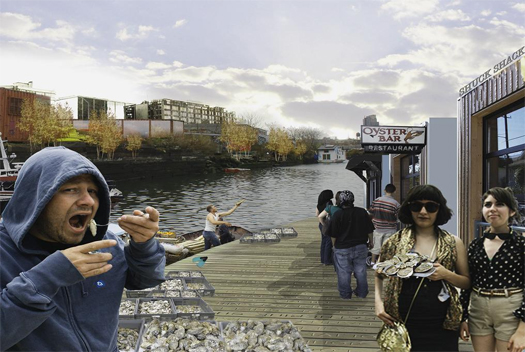

After detouring through a (rather fascinating) history of the evolution of traffic control (a history which reminded me of a recent tweet from the excellent Lost Angeles: “at the turn of the century, speed limits for the new cars were 8 mph in residential districts and 6 mph in business districts”), the authors turn to a discussion of the contemporary means of traffic control in Los Angeles, which they split into two categories, physical systems and virtual data. The former are described thusly:

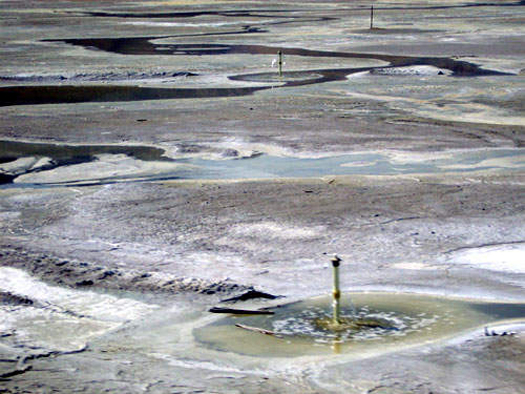

“…over 50,000 buried loop detectors — the insulated wire loops that passively detect subtle magnetic field changes from vehicles — combine with over 700 weatherproofed video cameras, some of which are remotely controlled to pan and zoom, to monitor and control traffic flow. Loops automatically trigger software in switching boxes linked to intersection signals, but also send data to TMCs that allow traffic engineers to monitor flow patterns and adjust timings remotely. A simple click of mouse button [in the control centers “ATSAC” (Automated Traffic Control and Surveillance) and “TMC” (CALTRANS’s Traffic Management Center)] can start or stop the flow of movement on the grid.”

Of course, as that description makes clear, the virtual and physical aspects of the modern traffic control apparatus are materially inseparable, as the data has neither host nor eyes without its physical appendages and the physical appendages are dead and useless unless the streams of information they host flows and is interpreted. If there is a real distinction to be drawn between the physical and the virtual aspects of traffic control, it is, as the authors note, that the physical appendages are persistent and static, moving only when maintenance workers crack open their housings, while the data the system hosts is “ephemeral and dynamic”.

[Inductive loops in Los Angeles pavement; photograph via CLUI]

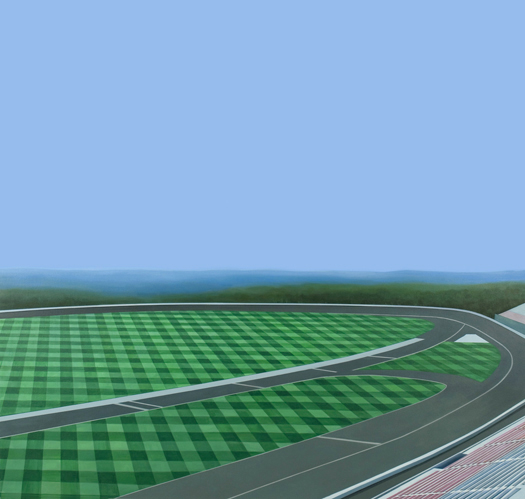

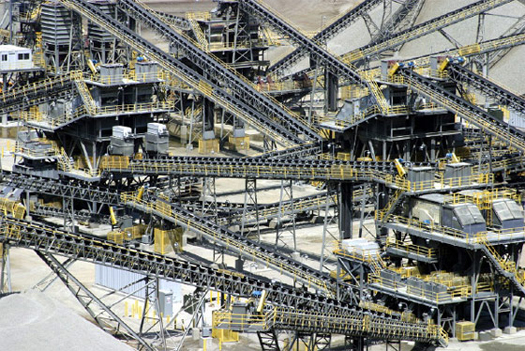

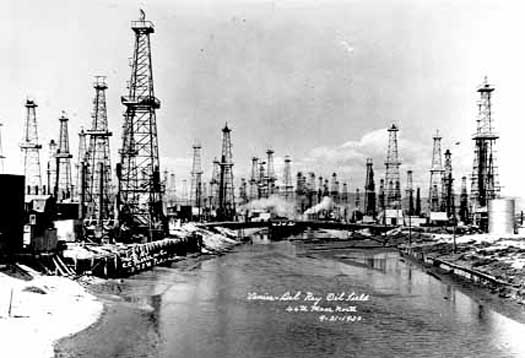

The final portion of the chapter discusses “incidents”, which are described as the re-introduction of the corporeal and embodied into the virtual system of traffic control – the smooth flow that the virtual seeks to enable is interrupted, human errors literally pile up on freeways and in the streets. This feedback between traffic control system and human agents, though, is not at all one way. Traffic (remember, “we are traffic”) and traffic control systems are functionally cybernetic: the driver’s foot on the gas pedal moves up and down in rhythm with the dictates of a city-spanning central nervous system, communicating as surely with the driver through the code of yellow, red, and green as the brain does with the arm. The traffic control system is extraordinarily complex, existing as networked ecologies do, at a multiplicity of scales. At some scales, it is easily experienced directly — the traffic light — while others can only be experienced through mediating systems or summaries, such as the traffic diagrams the authors have drawn. An inductive loop, for instance, can be understood both as a series of strangely beautiful markings in hot-poured asphalt (above) and as a single neuron in a massively complex system. Stepping back further, that massively complex system only functions a part of the irreducibly complex urban whole: without pit mines to produce aggregate, there would be no roads for traffic to fill; or, without the individual people who commute on the roads, there would be no need to coordinate signal timings.

The interesting fact that arises from the complexity of these co-evolved systems (and, as noted in Varnelis’s introduction to The Infrastructural City, from the primacy of individual property rights in L.A.’s political culture) is that, “as the possibilities for adding new highways — or even lanes — dwindle in many cities, most new progress is made at the level of code”. This shift which the authors identify is a part of a systemic shift in the methodology of urbanism, from plan to hack, that we’ve been fascinated with for some time now. In a mature infrastructural ecology, like Los Angeles, the city has developed such a persistent and ossified physical form that, barring a radical shift in the city’s political culture, designing infrastructure becomes more a task of re-configuration and re-use than a task of construction.

[The interior of ATSAC, via Swindle Magazine’s feature on ATSAC]

Initially, this may seem an extraordinarily frustrating condition for urbanists, who have of late been so interested in the possibility that the design of infrastructures might offer an alternative instrument for shaping cities, combining the intentionality and vision of the plan with the vibrancy and resilience characteristic of emergent growth. Infrastructures, we’ve noticed, can be a stable element which mold and manipulate the various flowing processes of urbanization which produce cities: economic exchange, human migration, traffic patterns, informational flows, property values, hydrologies, waste streams, commutes, even wildlife ecologies. Historically, governments and private developers have sought to harness this potential, whether by profiting from the sale of land along a new infrastructure or by supplementing existing infrastructure to reinforce growth and density in a locale (the initial growth of Los Angeles along privately-owned streetcar lines being one of the classic examples of the former sort of infrastructural generation). But if, as the authors of “Blocking All Lanes” suggest (and, I think it is fair to say, The Infrastructural City suggests as a whole), opportunities to plan and design new infrastructural frameworks are likely to be extremely rare in mature infrastructural ecologies, should urbanists abandon their interest in infrastructure as an instrument for shaping the city?

[Signal vaults in a traffic island, via CLUI]

I don’t think so, for two primary reasons.

First, the rarity and scarcity of those opportunities does not mean that they should not be seized when they are realistically presented. And when opportunities for the construction of new infrastructures within a mature city do occur, they are likely to appear in hack-like guises: concretely, like Atlanta’s Beltline, which utilizes a defunct rail right-of-way as the foundation for a new commuter rail line1, or Orange County’s Groundwater Replenishment System, which redirects the flow of cleaned wastewater in Orange County from ocean to aquifer; speculatively, like Velo-City‘s Toronto bicycle metro (which, as it happens, has a less-speculative southern Californian counterpart, the Backbone Bikeway Network). Go over, go under, re-deploy, tag along, piggyback.

Second, there are fantastic opportunities created by thinking about the architectural act as a hack rather than an object (whether or not the hack produces an object). These opportunities were one of the primary themes of our post on “the best architecture of the decade”, which included both examples of hacks that lack a traditional architectural object — the iPhone, Kiva — and architectural projects executed as hacks — Quinta Monroy, Parque Biblioteca Espana. Perhaps most relevant of the hacks cataloged there, given that the topic at hand is automobile traffic, is the MIT Smart Cities group’s CityCar, which utterly inverts the architectural methodology of the plan. Instead of designing a new form for cities, and then producing buildings which fit that form, the Smart Cities group has designed both a technology — the CityCar — and a series of ways in which that technology would interact with the city (as a battery in a smart grid, as a part of an even more advanced traffic control system that would adjust congestion pricing in real time to efficiently distribute traffic over time and space), confident that doing so will enable ways of life that will generate positive changes in the city. Notably, all these cases are new ways of utilizing existing infrastructures (the iPhone, Kiva, CityCar) or of thinking about architecture as an infrastructure (Quinta Monroy, Parque Biblioteca Espana). Infrastructure is not made obsolete by avoiding object fixation. Rather, it becomes increasingly important, as a material instantiation of non-corporeal forces and thus the potential physical locus of hacks.

In both cases — whether the hack is understood as a way of implementing a new infrastructure or as a new kind of architectural act — the key realization is that successful shifts in urban form will only happen when they are paired with successful alterations of the infrastructures, systems, and flows that generate those forms. Attempts to construct a new vision for the city that fail to grapple with the underlying systems that, like traffic, constitute and produce the city will ultimately either be ineffective or collapse catastrophically.

For additional reading on the physical infrastructure of traffic control, I recommend CLUI’s online exhibition, Loop Feedback Loop.