[Audience discussion during DredgeFest; photo by Nicola Twilley.]

One of the primary reasons that mammoth has been relatively quiet this year is the effort that Stephen and I, as two of the four current members of the Dredge Research Collaborative, have put into organizing DredgeFest NYC. We did this with no small amount of assistance from our generous hosts, Studio-X NYC, and, thanks to the latest component of that assistance, a full video archive of the symposium is now available. (The other component of the event, the boat tour, was recently covered by The Atlantic Cities here.)

Below, you’ll find the video archive of the symposium that I mentioned.

Before getting to that, though, I suppose this is also an appropriate point to talk briefly about why we organized DredgeFest NYC.

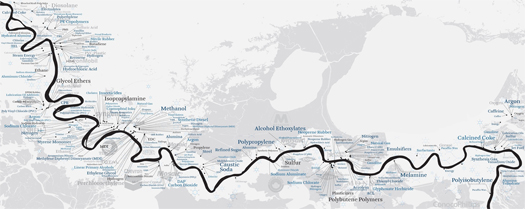

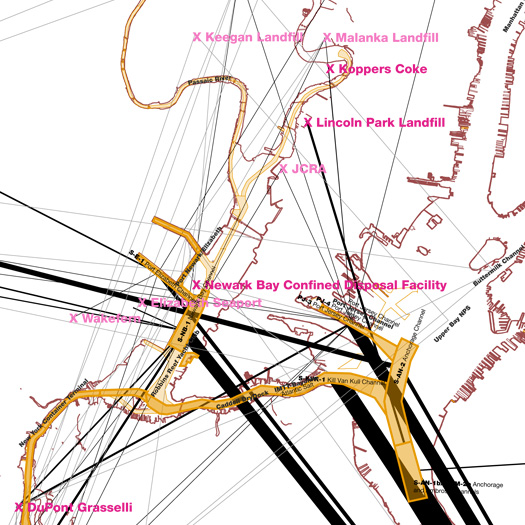

When we began our work as the Dredge Research Collaborative, we began with the intention of producing and publishing speculative design projects that would demonstrate the value that landscape architects and other designers might bring to the aqueous landscapes of dredge. As our initial projects developed and we began to enter into conversations with the engineers, corporations, and agencies that currently are responsible for shaping those landscapes, we realized that there were two major barriers to design participation in these landscapes. First, dredge is an invisible infrastructure. It is essential to economic and environmental processes in nearly every contemporary estuarine city, but it is rarely a topic of public conversation. Second, though there is a growing interest in such landscapes within landscape architecture, that interest has remained primarily speculative, in large part because working relationships between designers and those actors with actual agency in the landscapes of dredge simply do not exist.

DredgeFest is our effort to grapple with these problems. By organizing public events, we are seeking to open up a public conversation about the dredge cycle, at once documentary and speculative, while using the events as an opportunity to build connections between disparate communities. Thus while we were thrilled by the diverse group of panelists who agreed to join us and the even more diverse audience who attended DredgeFest NYC, we were probably even more excited to see specific connections occurring between the design community and the dredging community, like the Army Corps engineer who approached one of our collaborators, Gena Wirth, after the event, excited about the mapping work she had done with us and hoping that she would be interested in expanding on that mapping work in collaboration with the Corps.

We think that this kind of cross-pollination is not only exciting, but essential. This week’s events have emphasized and underlined — in tragic fashion — the importance of designing urban littoral environments, of recognizing and meeting the challenges that rising and warming seas will pose to coastal cities in coming decades.

DredgeFest NYC: Video Archive

The first video, which contains an introduction to the event delivered by Brett and I, is embedded immediately below this paragraph. Below the first video, you’ll find the schedule as a list of talks and panels, with links to the video for each presentation or panel. (A full list of the videos can be found here, in Studio-X NYC’s own video archive.)

Dredge and the Anthropocene

We introduced the idea of dredge as a process that is interconnected with a much larger regime of human sediment handling practices, and examined ways that humans act as geologic agents.

Lisa Baron (USACE): Dredging and Dredged Material Management in NY/NJ Harbor

Andrew Genn (NYCEDC): The Beneficial Reuse of Dredge

Roger Hooke (University of Maine): How Humans Have Shaped the Landscape

Panel: Baron, Geen, Hooke, and Michael Ezban (Vandergoot Ezban Studio)

Circularity and Feedback

We examined the current evolution of the handling of sedimentary resources from 20th-century linear industrial models towards 21st-century methods that create cycles, positive feedback loops, and resilience in the face of contemporary environmental challenges. This section featured leading practitioners who explained how their work participates in and even accelerates this paradigm shift.

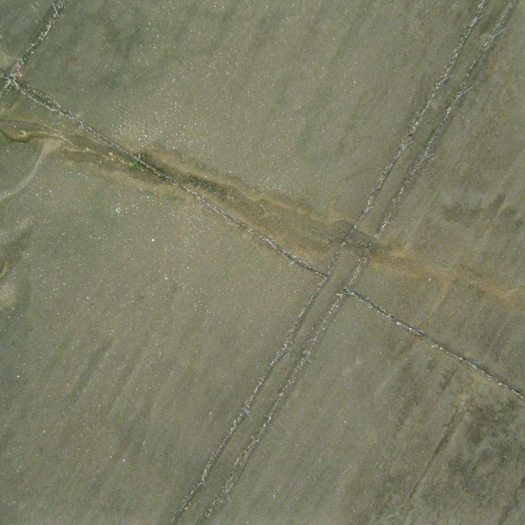

Bill Murphy (e4sciences): Geophysical Imaging for Sustainable Engineering – NY Harbor Deepening

Douglas Pabst (EPA): Sediment Management in NY/NJ Harbor

Edgar Westerhof: Green Solutions With Geotextile Tubes – a Dutch Perspective

Vicki Ginter (TenCate): TenCate Geotube Technology

Catherine Seavitt Nordenson (Catherine Seavitt Studio, CCNY): Adaptive Sediments – Dredge and Drift

Regeneration and Public Participation

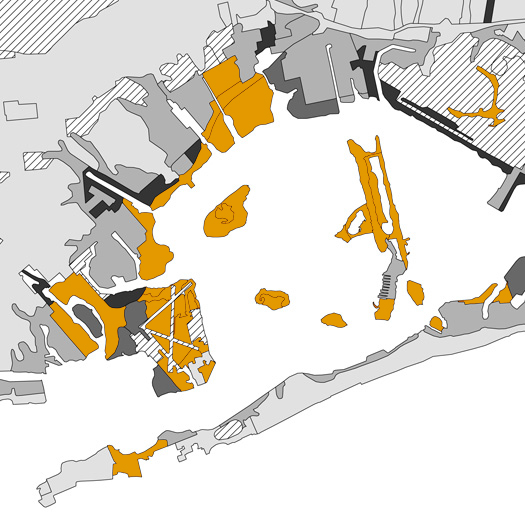

We examined the emergence of dredge as a resource for environmental regeneration, like the current restoration of island wetlands within Jamaica Bay using dredged material from channel deepening projects. This section also highlighted the grass roots of dredge, with a panel of practitioners who enable public participation through their work.

Kate Orff (SCAPE, Columbia GSAPP): Future Landscape – Remaking New York’s Harbor

Phillip Orton (Stevens Institute of Technology): Guiding Coastal Adaptation with Hydrodynamic Modeling

Panel: Orff, Orton, Dave Avrin (NPS), Hans Hesselein (Gowanus Canal Conservancy), and Debbie Mans (NY/NJ Baykeeper).

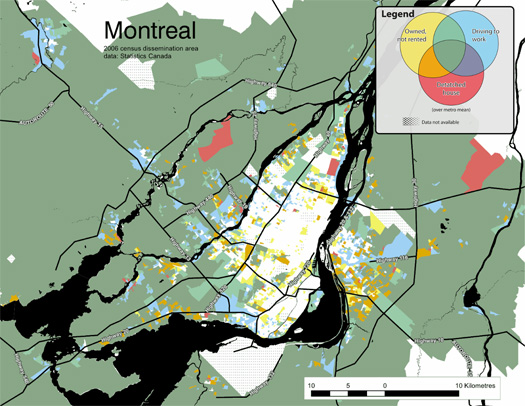

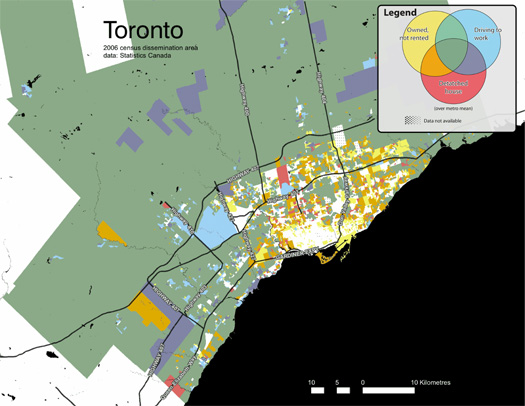

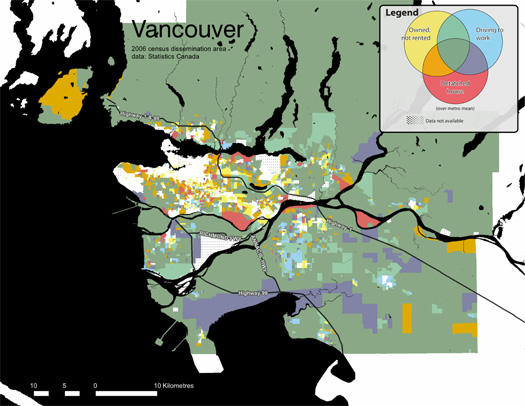

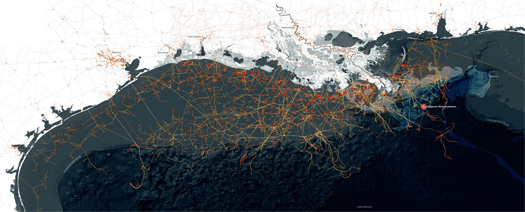

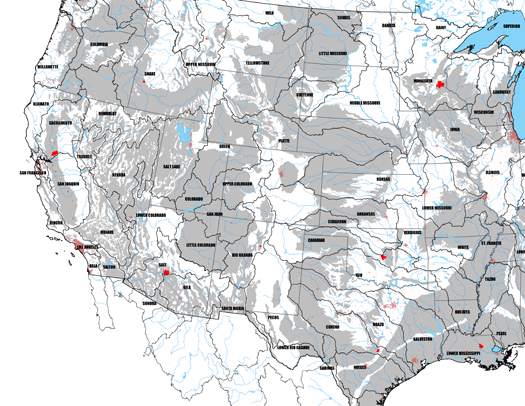

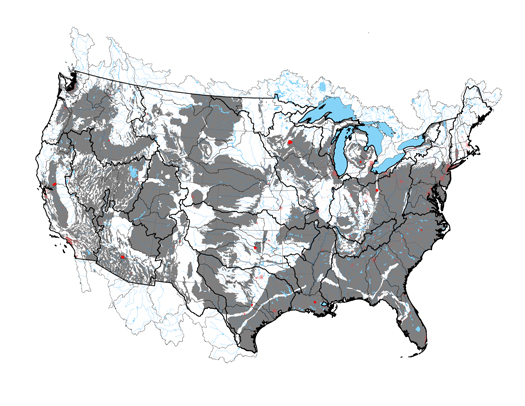

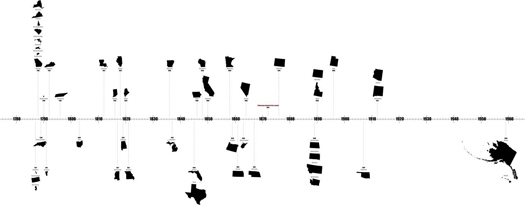

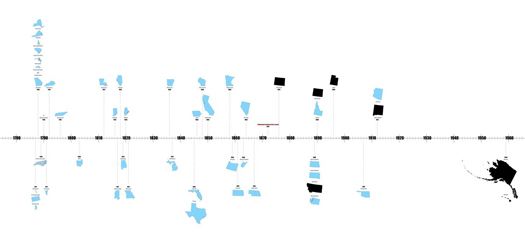

The list of people that to whom we owe thanks for making DredgeFest possible is rather long. As mentioned before, we were hosted by Columbia University GSAPP’s Studio-X NYC — Nicola Twilley, Geoff Manaugh, and Carlos Solis. We were supported by the generous sponsorship of Arcadis, TenCate, and TWFM Ferry/American Princess (the last of which was the boat that took us out into the harbor — we can’t recommend Tom Palladino and the crew highly enough), making the event financially plausible for us as organizers. Alex Chohlas-Wood and Ben Mendelsohn put together the event trailer that we posted in early September, and are working on a longer follow-up that is sure to be fantastic. Seth Denizen and Gena Wirth contributed original maps and drawings to the exhibition that greeted attendees at the door, which I intend to post about in more detail soon. It was also extremely rewarding to see everyone who turned out, on both days, to share our enthusiasm for and belief in the importance of understanding and designing landscapes of dredge. Finally and perhaps most importantly, we were thrilled by the enthusiasm and efforts of the speakers and panelists, without whom there quite literally would have been no event.

![20120227_Watershed_Mods_Number [Converted]](http://m.ammoth.us/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/21_small.jpg)