0. Everyone’s favorite Donald Rumsfeld quotation: “[T]here are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – there are things we do not know we don’t know.” (As evidence that this is everyone’s favorite Donald Rumsfeld quotation, I submit that (a) it has its own Wikipedia page, the wonderfully-titled “There are known knowns”, where debate over its profundity or lack of profundity is documented, and (b) that Rumsfeld himself titled his autobiography Known and Unknown.)

Tetrapods deployed off the Japanese coast near Toyama (top) and Niigata (bottom). An old article in the New York Times reports:

“‘The [Japanese] construction state is in some respects akin to the military-industrial complex in cold-war America (or the Soviet Union), sucking in the country’s wealth, consuming it inefficiently, growing like a cancer and bequeathing both fiscal crisis and environmental devastation,” Gavan McCormack, a professor of Japanese history at Australia National University, wrote…

In the [1990s], public works spending has been stepped up even more to stimulate a languid economy…

…Japan uses as much cement each year as the United States, despite having only half the population and only 4 percent of the land area.”

The tetrapod — a concrete coastal armament used to solidify coastlines and arrest erosion — is symbolic of this metastasized public works state, as there is little constituency opposing their placement and thus tetrapodding typically proceeds more quickly than other projects, so that roughly half of the Japanese coastline has been so armored.

1. GAMES

Last December, I had the pleasure of sitting on the jury for the final reviews of Jorg Sieweke’s landscape studio at UVa, which was exploring various design scenarios for a hypothetical shift of the Mississippi River from its current course to the course it “naturally” desires to take through the Atchafalaya Basin. (This was particularly enjoyable given that I’d accidentally spent the summer blogging about flooding in general and flooding on the Mississippi River in particular.)

[0] I think this set of problems is occurring concurrently in the broader/parallel world of architectural design, so, throughout this post, I’ll shift between talking about architectural design and talking about landscape design, without being particularly clear about boundaries between those two things. Of course, that’s what we usually do here.

One of the student projects proposed a kind of abstracted board game which attempted to codify the interactions between the insurance industry, various economic activities in the Atachafalaya Basin (such as gambling), floods, disaster management systems, public space, and citizens of the flood-prone Basin. This project intrigued me greatly — but it did so less because of its resonance with the recent vogue for “gamification” (where I am inclined to agree, for the most part, with Ian Bogost), and more because it helped me articulate a set of problems related to aggregation, complexity, perversity, and misalignment in the design of landscapes0.

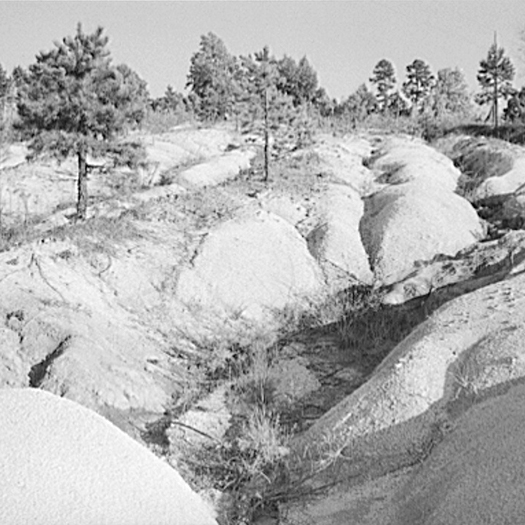

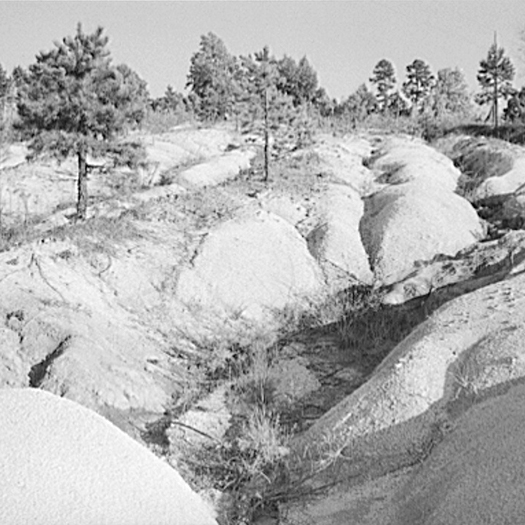

The soils of the Southeastern Piedmont — from Alabama to Virginia — suffered terrible erosion as a result of short-sighted agricultural practices in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. The prevailing agricultural economic systems of that region during those times — slavery and share-cropping — both encouraged short-sighted practices, as the men and women working farms and fields did not own the land, and so had little incentive to care for its long-term health, even as farming techniques that would have arrested or prevented erosion were well-known.

David Montgomery’s fascinating Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations recounts the travels of the British geologist Charles Lyell through the antebellum South:

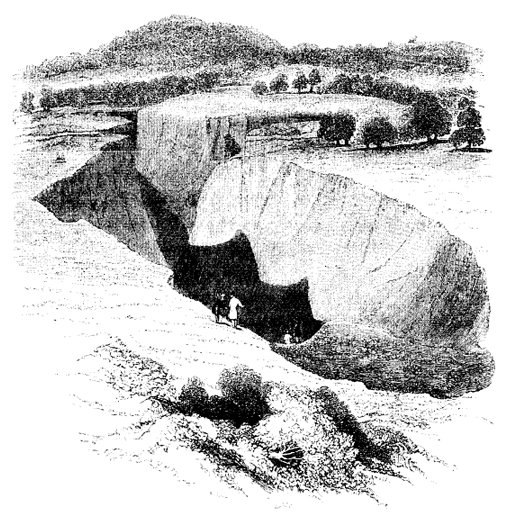

“[Lyell] stopped to investigate deep gullies gouged into the recently cleared fields of Alabama and Georgia. Primarily interested in gullies as a way to peer down into the deeply weathered rocks beneath the soil, Lyell noted the rapidity with which the overlying soil eroded after forest clearing. Across the region, the consistent lack of evidence for prior episodes of gully formation implied a fundamental change in the landscape. “I infer, from the rapidity of the denudation caused here by running water after the clearing or removal of wood, that this country has always been covered with a dense forest, from the remote time when it first emerged from the sea.” Lyell saw that clearing the rolling hills for agriculture had altered an age-old balance. The land was literally falling apart.

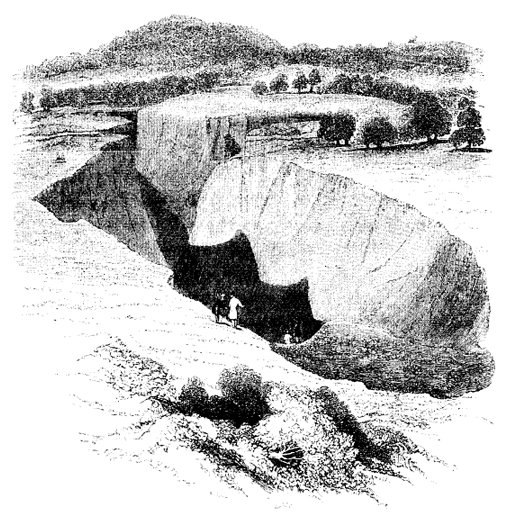

One gully in particular attracted Lyell’s attention. Three and a half miles west of Milledgeville on the road to Macon, it began forming in the 1820s, when forest clearing exposed the ground to direct assault by the elements. Monstrous three-foot-deep cracks opened up in the clay-rich soil during the summer. The cracks gathered rainwater and concentrated erosive runoff, incising a deep canyon. By Lyell’s visit in 1846, the gully had grown into a chasm more than fifty feet deep, almost two hundred feet wide, and three hundred yards long. Similar gullies up to eighty feet deep had consumed recently cleared fields in Alabama. Lyell considered the rash of gullies a serious threat to southern agriculture. The soil was washing away much faster than it could possibly be produced.”

The top image is soil erosion in Mississippi (not, of course, in the Atlantic Piedmont — but sharing the same economic systems), photographed by Evans Walker in 1936 and via the Library of Congress; the bottom image is soil erosion on a farm in Caswell County, North Carolina, photographed by Marion Post Walcott in 1940 and also via the Library of Congress. The image at the top of this post is, of course, Charles Lyell’s illustration of the gully described above, reproduced in Dirt.

2. CRASHES

A series of talks that I’ve listened to in the past year also helped frame these problems for me. The first is an interview on Terragrams with Case Brown, currently of P-REX; the second, Kazys Varnelis’s “A Manifesto for Looseness”; and the third, Kevin Slavin’s “Those algorithms that govern our lives” (or, the somewhat shorter TED version, “How algorithms shape our world”). To explain how they’re relevant to the set of problems within landscape design I’m after, I think it’s best to take them in reverse order.

The central thesis of Slavin’s talk is roughly that programmed algorithms — embedded in and running financial systems faster than humans can react, controlling Roombas, determining price points on Amazon — are participating in the construction of a world that is increasingly designed to suit them and encoded with their logic. This has a pair of weird effects: first, algorithms begin to manifest physically (James Gaddy, describing Slavin’s talk, writes “he describes a fiber optic canal that was dug between New York and Chicago to deliver stock market information microseconds faster, and the way buildings are being carved out from the inside to house trading servers”) and second — and of more interest to me here — algorithmic systems have the tendency to exhibit suddenly bizarre behaviour, like an algorithm on Amazon.com pricing an unremarkable used book at $23 million1. Algorithmic systems are thus prone to the kind of sudden and unpredictable bifurcations that Manuel DeLanda describes in the introduction to A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History, switching with little apparent warning from a seemingly stable state to something considerably more extreme or erratic:

“Ilya Prigogine revolutionized thermodynamics in the 19060s by showing that the classical results were valid only for closed systems, where the overall quantities of energy are always conserved. If one allows an intense flow of energy in and out of a system (that is, if one pushes it far from equilibrium), the number and type of possible historical outcomes greatly increases. Instead of a unique and simple form of stability, we now have multiple coexisting forms of varying complexity (stable, periodic, and chaotic attractors). Moreover, when a system switches from one stable state to another (at a critical point called a bifurcation), minor fluctuations may play a crucial role in deciding the outcome.”

We might say that algorithmic systems, because of they follow programmed rules strictly, are prone to rapidly becoming far from equilibrium.

Kazys Varnelis’s “A Manifesto for Looseness”, meanwhile, addresses the way that complex systems are, despite — or maybe really because of — their sophistication, vulnerable to crashes. Talking about the research of sociologist Charles Perrow, Varnelis says:

“…creating tightly coupled systems, very complex, finely tuned, highly efficient systems, in which one part’s operation is closely dependent on another’s, and when we add all these together, we can achieve remarkable levels of efficiency. The result is that these systems, because they are so integrated, can fail in unpredicatable ways. One part fails — a sensor — this has a cascading effect on another part, which exceeds its tolerances. This makes another part fail; and so on, and so on. This leads to anomalous readings on a number of sensors. Operators can’t figure out what’s going on; personnel become overwhelmed. They don’t understand what’s happened; they make the wrong decisions. Things get worse. Nobody knows what to do… Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, Fukushima, the Challenger disaster, the Columbia disaster… Don’t blame the operator — blame the complexity designed into the system itself.”

The algorithmic systems that Slavin describes are, obviously, a subset of complex systems generally and, insofar as they occasionally have something like an operator (though an important part of Slavin’s thesis is the argument that algorithms are increasingly defined by our general inability to comprehend or ‘read’ the ones that shape our world), the operator clearly cannot be faulted for failing to react with algorithmic speed to the actions of the algorithmic system. The kind of cascading failure that Varnelis describes by way of Perrow is, it seems to me, a perfect example of what a rapid bifurcation where “minor fluctuations… play a crucial role in deciding the outcome” looks like, played out in real time. And that minorness — the smallness of the critical fluctuations within the overall scale of the system — is precisely what makes them difficult for the operator to predict, anticipate, or even observe. (Replace “operator” with “designer” in that last sentence, and you’ll have a hint of where I am going with this.)

Third, I mentioned Case Brown’s interview on Terragrams: Brown is principal researcher for P-REX and, most relevantly here, recent recipient of the Rome Prize in landscape architecture, where he studied the Roman villa system, “the ancient… agricultural complex that spread the empire, fed the armies and grew the surpluses to make senators rich” as an early example of a real estate bubble:

“The rise and crash of the Roman villa system reads eerily like the modern story of American foreclosures — profit schemes of land speculation, securitized and excessively mortgaged properties, rapid expansion and even more rapid decline. … As a system, they provide a marvelous example of combining a food economy infrastructure and an elite leisure system, all the while staking claim to an enormous empire. How did this economy operate and did the Romans overextend their land ventures as many have in the modern United States?” Brown asks.

He said it is the nature of these markets to bloat beyond their own means, and the tendency continues today with such examples as oversized American vacation homes, elaborate golf course communities in China or ambitious skyscrapers in Dubai.

“We tend to overextend markets with gluttonous consistency. All these forms of extra-urban development, ancient and modern, draw on a common set of market-exploitation tendencies. Fertile land, urban respite and profit have provided the skeleton for centuries of speculation. To be able to document the birth of this trifecta could reformat our current landscape speculative practices,” Brown said.

Here, in a speculative system, the collapse is perhaps a bit more predictable than within the algorithmic or complex system — with every bubble, there are those who recognize the bubble before it collapses — but the result is the same: a disastrous and typically sudden crash. In all three kinds of systems, I think, crashes can be said to originate with the actions of individually rational parts acting, in aggregate, in accordance with perversely misaligned incentives. The algorithm, for instance, is based on a model of the “real” world (“real” being in quotation marks because the algorithm is, of course, as real as anything else), and when that model is even just slightly misaligned with the world it models, the aggregate nature of algorithms — algorithms always flock — produces outcomes that are rapidly perverse: $23 million used books, “flash crashes”.

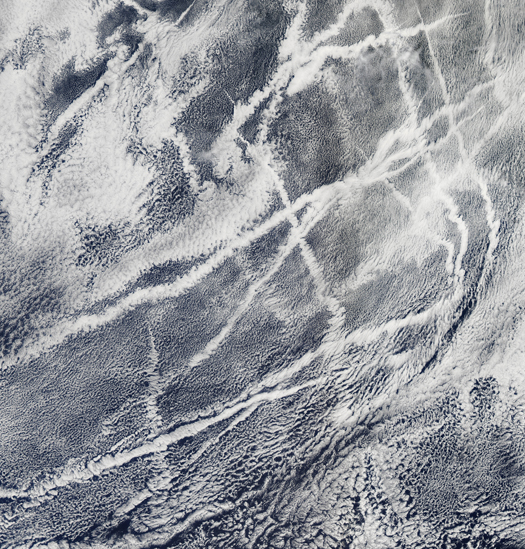

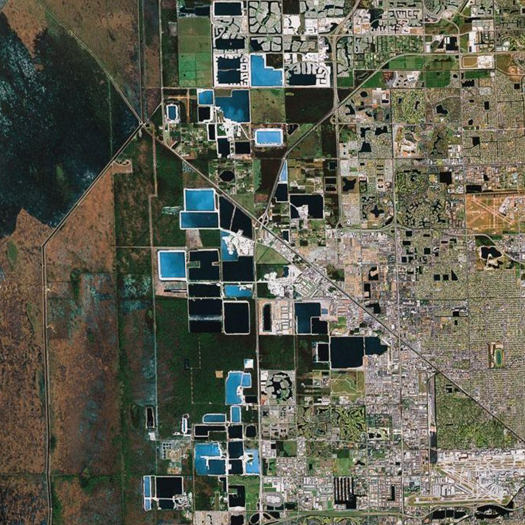

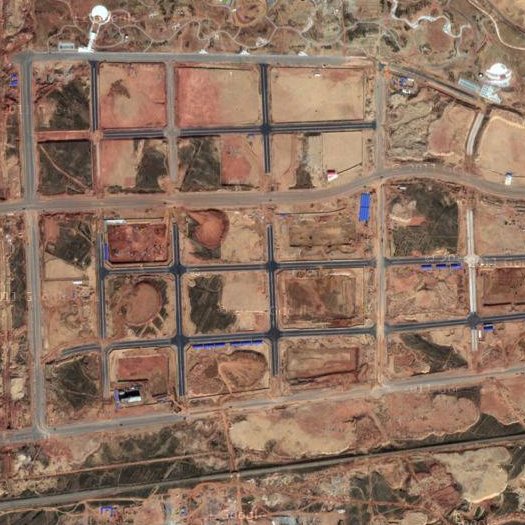

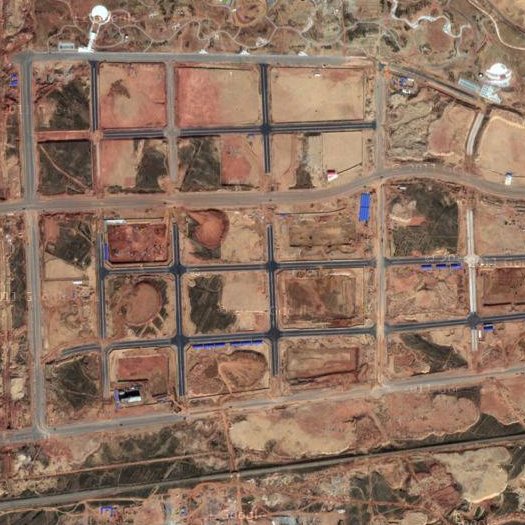

An empty street grid (top) and unfinished residential towers (bottom) in Ordos, the coal boomtown in Inner Mongolia made famous by a

2009 Al Jazeera report describing it as “China’s empty city”, its growth propelled by a heady mixture of new wealth generated by the coal boom, local state policies responsible for planning and providing infrastructure for a huge new city in the desert, and national state policies that opened up real estate speculation as one of the few investments available to private individuals; images

via google maps.

3. DISTRIBUTION, AGGREGATION, AND DISAGGREGATION

Returning to the studio I reviewed at UVa: there were several other projects, in addition to the one explicitly referencing game design, that struck me as broadly representative of a trend in architectural design (and particularly landscape architecture) towards proposals that rely on aggregation and distributed components to drive beneficial change. For instance, one proposed distributing the functions of rainwater control and freshwater supply to individual units located on each city block and shared by the inhabitants of that block; another set up a system for collecting fecal matter and turning it into productive soil, again on a small scale, and with collection incentivized by small scale economic rewards (“bring your morning shit, get a morning cup of coffee”). Typically, I think, what such proposals have in common is that they design distributed systems that rely on incentive structures to guide individual actors towards making individually rational decisions with collectively beneficial consequences. (In that, these proposals might be understood as something like neoliberal architectural design, with neoliberal intended here to be simply descriptive, neither derogatory nor laudatory.)

These kinds of proposals are increasingly common: witness the proliferation of projects hoping to find some alternate use for vacant lots at a city-wide scale or the vogue (particularly in student work, which I take as an indicator of future disciplinary trends) for “tactics” (the (genuinely excellent) GSD student publication “Tactical Operations in the Informal City” is typical of this vogue: “the students were asked not to develop a master plan for the whole city, but rather to propose one or two interventions that could initiate a chain reaction of improvement”). A reliance on distributed components and aggregated effects is even making in-roads into surprising places, as in the case of the New Urbanism’s enthusiastic embrace of “Tactical Urbanism” (though, if there is anything consistent about the New Urbanism, it is that it has remained enduringly flexible as an ideology, seeking to co-opt and absorb counter-movements, as Duany wrote in a fascinating article for Metropolis last April that I’ve always intended to write at more length about), an embrace which has been well-received in and amplified by the broader urbanist community on the internet (see, for instance, the chord that the Atlantic Cities‘ coverage of a so-called “guerilla wayfinding” project in Raleigh struck).

And mammoth has both often praised projects in this vein — such as Visual Logic’s excellent Backyard Farm Service or, in our “Best Architecture of the Decade”, where we claimed Kiva as an architectural actor — and proposed them ourselves. (For that matter, the projects I’ve referred to from the studio at UVa were — in no small part due to their participation in the project of distributed design — among the stronger projects in that studio.) Rhetoric surrounding the incorporation of resilience as a primary goal into design — rhetoric which we have encouraged — also typically promotes the dissolution of centralized structures into networks of smaller components which will function in aggregate towards some goal. (I also think this interest extends beyond human actors, towards harnessing the aggregate behaviors of variegated non-human actors like tides, clasts, markets, microbes, brick-laying drone helicopters, and alligators.)

[2] I also find it intriguing that both studio work and the practice of architectural design have a certain meta-resonance with games. That is, studio and practice could both be understood as games — structured sets of rules that aim to map reality that nonetheless exhibit disconnects with the reality they map at various points — even if both studio work and practice tend to have more sophisticated rule systems than the vast majority of games, which makes it harder to notice those disconnects. In both cases, it is interesting to note what is included and what is excluded from the game.

So I intend to phrase my concern here within the context of a deep appreciation for the merits of the general project of distributed design which, at its best, offers a more democratic, more organic, and more resilient alternative to heavily centralized, fracture-prone strategies. But I am wondering: when designers set up complex systems reliant upon the alignment of incentives to channel the swarming and flocking behavior of aggregate wholes towards beneficial ends, is there any thought going into the potential of that very same kind of behavior to magnify small mis-alignments into major crises — mis-alignments that may have been so small as to be invisible to the original designer or which (worse) the original designer may have had her own incentives to ignore? What would be the landscape effect equivalent to the weird behavior that happens at the margins of a video game — or a financial crisis? Where does aggregated behavior cascade through glitches into perverse results2? Where do individually rational behaviours become collectively irrational? What are the dangers in assuming that everything goes according to plan?

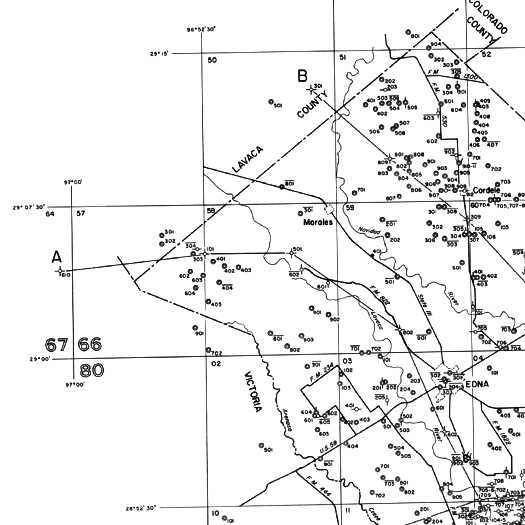

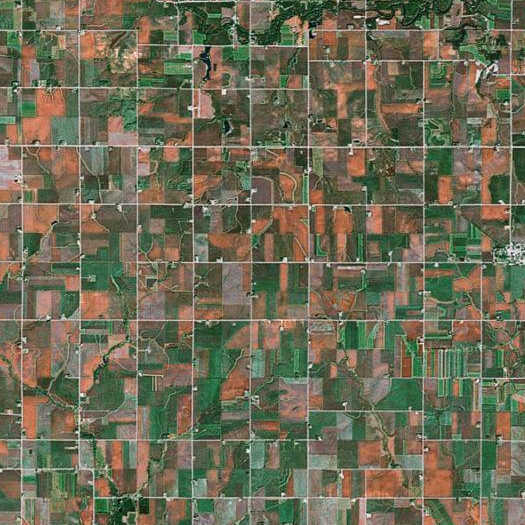

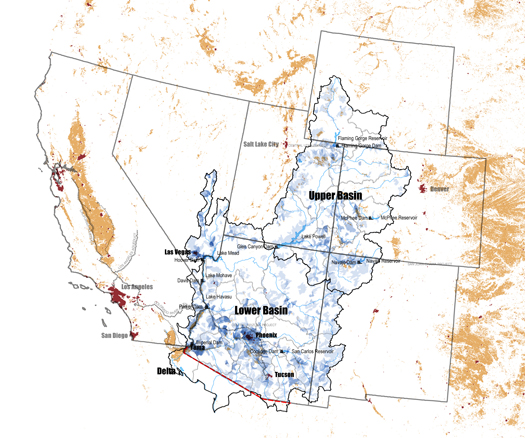

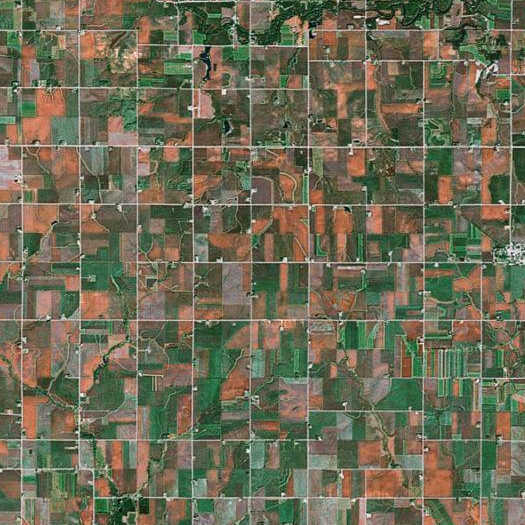

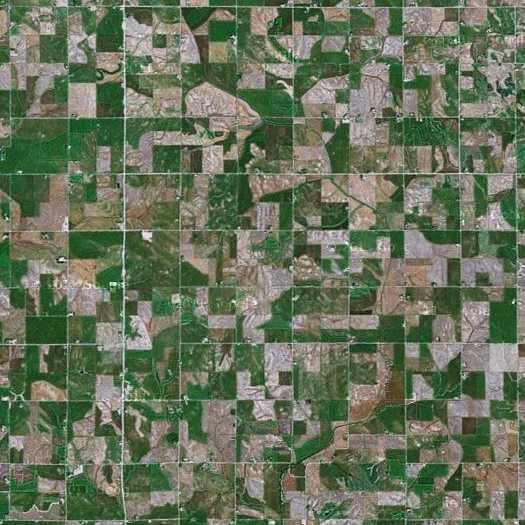

Cropland in Iowa, whose land use is thoroughly dominated by agriculture — roughly ninety percent of the state’s land is in use for agricultural production, and more of that land is cropland than in any other state (well,

at least by this source; I’ve also seen indications that it might be Nebraska). While Iowa’s land was originally converted into cropland by settlers attracted by a fertile combination of climate, soils, and topography, the current dominance of that land use can at least partially be

attributed to federal subsidies, particularly for corn and soybean production, which tilt market dynamics in favor of farming cash crops. Thus Iowa might be said to be

an agricultural freakology (the ecoregion it is in is named not for a defining natural feature — like the “Northern Glaciated Plains” or “Mississippi Valley Loess Plains” — but for the crop that dominates it: “

Western Corn Belt Plains“), sustained in part by the perverse misalignment of incentives.

4. SAFEGUARDS

If the misalignment of incentives is an obvious potential problem with design that relies on directing aggregate behavior through incentives, then there is an obvious need for safeguards — for structures within a design proposal that will contain the risk of cascading failures.

Thus I suggest that these projects should anticipate failure, which (ironically? I guess?) indicates that they should be particularly concerned with systemic resilience. That is, they should be designed not to finely-tuned limits of tolerance, but with enough give that they can withstand the accidents, perversions, and even crashes that will inevitably result from the misalignment of incentives in unpredicatable ways. Furthermore, they should explicitly acknowledge the presence of “unknown unknowns”. While it is logically impossible to anticipate specific unknown unknowns, it is quite possible to anticipate misalignment and perversity generally. The tendency, I think, in making these kinds of proposals — and this is very much what Stephen and I did in our proposal for Luanda, for instance — is to construct proposals on the basis of best-case scenarios, considering only first-order failures, where first-order failure is defined as the problems that the project responds to and second-order failure is defined as the problems that are potentially generated by the proposed response. In a way, this suggests that designers need to become better futurists, though that may often mean being a futurist at relatively small temporal and spatial scales.

If architects and landscape architects accept that it is probably impossible to set up perfectly aligned incentive structures, but still want to take advantage of their potential, then we’ll need to have mechanisms in place to protect against misalignments that we know are both unpredictable and inevitable. There’s a lot of talk about what those mechanisms look like in the financial world, for example; what would they look like as a component of the design proposal or design initiative?

[Parts of this post emerged out of conversations with Stephen, Brian Davis, and Brett Milligan; in particular, Brett suggested the example of Iowa as an unnatural ecology produced by misaligned incentives. As noted in one of the footnotes, this is all closely related to my interest in the landscapes of global financialization — which are typically spectacular case-studies in the landscapes thrown off by the misalignment of incentives — and so, if you enjoyed this piece, you might want to also check out Metro International Trade Services.]