Alec MacGillis has an appropriately harsh look at a decade of Richard Florida in the American Prospect.

[via @loudpaper]

Alec MacGillis has an appropriately harsh look at a decade of Richard Florida in the American Prospect.

[via @loudpaper]

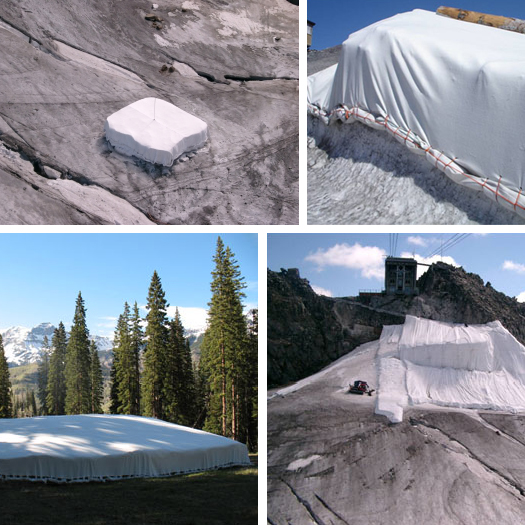

[“Ice Protector OPTIFORCE®”, in situ; images via Eiger International]

Or, the second implement in a developing toolbox of landscape tactics for the deployment of snowed architecture: a new f*cking wilderness reminds me that the Swiss have been wrapping their snow to preserve it (and their ski slopes) through the summer, hoping to stave off the melting of their glaciers. The wrap is plastic, or, more specifically, rolled sheets of polypropelene 3.8 mm thick, nearly 5 meters wide, and 55 “running meters” long. These sheets, brand-named Ice Protector OPTIFORCE®, are manufactured by the Landolt Group, whose portfolio includes various specialized woven, non-woven, and geotextile fabrics.

In addition to that strong European market, Ice Protector has begun to make a bit of an inroads in North America, with recent tests at “three major ski areas” in Colorado as well as the “Snowtorium” in Jackson Hole, a sculpted ring of snow wrapped in winter and unveiled on the fourth of July to face Wyoming’s summer sun. One scientist, Ohio State University’s Jason Box, has been conducting field tests on Greenland’s glaciers, hoping that Ice Protector might not only preserve the recreational landscapes of the wealthy, but also prevent glaciers from contributing to rising floodwaters across the globe (video of Box’s plan here).

And browsing Pruned‘s archives and re-imagining mountain-derived tactics such as Ice Protector for urban landscapes, you might begin to fill out that toolbox: not just snow plows and glacier wraps, but also screens that harness the harsh winds spilling between skyscrapers to cool and preserve snow (or redirect its fall mid-air), patented funnels tapping snowy banks like enormous faucets and arching streams of snow across crosswalks, and lines of bright-orange fencing controlling drifts and altering the patterns of piles pushed onto side streets by municipal plows; maybe even pulling your whitesward up snowed slopes and onto and into buildings. All of it at the mercy of wind and sun and erosion and accumulation: winter’s quick geology arrayed on a scaffolding you design, but never quite contoured as you’d intended.

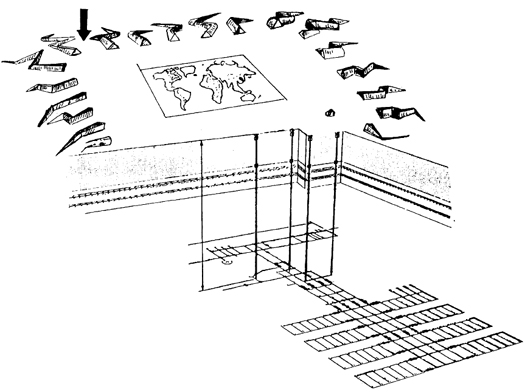

[Manhattan skyscraper zoning ordinances, given visual form by Hugh Ferriss; image from Kosmograd’s flickr account]

I’m not always the biggest fan of Andres Duany’s work1, but he throws out some interesting ideas in this interview with Builder Magazine: McMansions renovated as “11-bedroom, 11-bath boarding houses for senior citizens”, agricultural subdivisions (in which “the same crews that would ordinarily maintain the ornamental landscape in a golf community are instead assigned to the heavy work of the agriculture”; insert commentary a la Mike Davis here, your appetite for which will be whetted by visiting the website of Sky Florida, one of said agricultural subdivisions), and, perhaps most usefully, talks about urban design primarily in terms of alterations to legal structures — codes and zoning ordinances. Of course, the latter has been an essential component of the New Urbanist agenda for years and is not so different from how urban planners talk about building cities, but the usefulness comes from an architect talking in that fashion.

Regardless, there’s no reason to think that New Urbanism’s techniques, usually employed in service of things often better but still banal, couldn’t be deployed in a far more interesting manner. The idea that urban design can consist primarily of offering alternatives codes, downloadable and offered freely to small towns from Florida to California, constructing a sort of competitive marketplace for design guidelines, or guerrilla zoning ordinances, pieces of apparently innocuous legalese injected (perhaps figuratively, through democratic process, or perhaps literally, as municipal file servers are hacked at night by teams of rogue architects) into the DNA of nondescript suburban outposts in order to enable mutant aberrations in the form and function of both greenfield developments and detached single-family homes, is at the very least the kernel of a fascinating project, as I expect the results would be quite different if you asked a group of architects to execute an alternative code than they are when planners do the same.

[Related and previously on mammoth: The house is not a machine for living, but for making money; also, if you did begin the hack the DNA of building regulations and zoning codes, you’d want a practice like BIG around to exploit your hacking, to bring the legal strictures to life by “inflat[ing] [their] buildings” until they “hit the invisible immaterial boundaries” you’ve altered, revealing that the lines of ordinance you wrote were in fact a sort of negative sculpture (quotes from Will Wiles’s review of Yes is More in Icon); Spillway recently mentioned Ferriss’s drawings as a precedent for BIG’s architecture.]

I’m entranced by the simplicity (and, in retrospect, obviousness) of the suggestions in the short text accompanying Sergio Lopez-Piñeiro’s series of photographs at Places, entitled “White Space”. Lopez-Piñeiro says:

…even everyday plowing practices — practices with no artistic or design ambitions — have the capacity to transform snowed-in parking lots into beautiful winter gardens… We might see these utterly banal parking lots as project prototypes. The white parks that I envision could be easily constructed: plowing master plans would carefully locate the snow mounds, and the resulting designs would artistically exploit the spatial conditions defined by these usually overlooked piles of snow.

Indeed: why think only of the activities within an urban park seasonally, but not also the layout and arrangement of the spaces within the park? In the summer, perhaps it is Tschumi’s Parc de la Villette, studded with architectural follies and programmed for intensely urban uses, but in the winter, it is a snow-built Prospect Park, all the lazy and rural curves evoked by Lopez-Piñeiro’s coinage of “whitesward”. Or perhaps (as I think Lopez-Piñeiro is suggesting) the park itself is seasonal: in summer, the parking lot for Target; in winter, Worcester’s Boston Common, evacuated for three weeks after Thanksgiving to accommodate frenzied shoppers, but otherwise from first snow to final melt a constantly altering suburban playground, an annual and eerily fast simulacrum of geological processes of accumulation and erosion.

[The image above is from said series.]

Adrian Lahoud has a thoughtful response to mammoth‘s earlier post “infrastructural urbanism and fracture-critical networks” (itself a response to another post by Lahoud on a recent studio he led), discussing how to properly read studio proposals, the master plan “as only an incitement to conversation rather than the conclusion of one”, Lahoud’s ambivalence about the absorbing contingency into the design process, and the possibility that “the failed project of modernity must be repeated”.

While this recent Infrastructurist post (entitled “Reasons Not to Bike to Work: You Can Die”) on the sad news of another cycling fatality is unfortunately an excellent example of the importance of remembering that data is not the plural of anecdote, The Next American City has an excellent post by David Alpert (of Greater Greater Washington) which begins with observations about the city seen from the bicycle seat by David Byrne (who, in addition to being a musician, is the author of the recent book Bicycle Diaries), notes the lack of bicycle infrastructure in most American cities (with Portland as a positive exception), discusses regulatory and bureaucratic barriers to the construction of bicycle infrastructure (for instance: federal rules require “a detailed air quality conformity analysis” before approving new bicycle lanes), and finishes with practical steps both to take and being taken to promote bicycle infrastructure.

I’d like to echo Rob’s delight at being able to attend the final critique of the Landscapes of Quarantine Studio in NYC hosted by BLDGBLOG and Edible Geography. We’ll make sure and keep folks posted on the details of the studio’s exhibit at the Storefront for Art and Architecture, which is due to open in early March. I can’t wait to see what the participants develop.

Coming away from Saturday’s discussion, I couldn’t shake my fascination at the potential quarantine has to shape novel economies within existing systems – a line of thinking drawn from Front Studio’s project. They investigate the spatial and social implications of having a quarantined city-within-a-city. Proposed are a variety of tactics for segregating populations in an integrated environment, including appropriating under-utilized city and building infrastructure (such as fire escapes and phone booths) for a quarantined population’s circulation and disinfection; and color-coding portions of building facades (and scenting the infected population) as stay-away signifiers for the healthy population.

As is brilliantly communicated to the citizens of New York in Amanda Spielman’s project, NYCQ, disease spreads on virtually everything. Because goods are equally (along with people, and, apparently, pets) disease vectors, the simultaneous integration and bifurcation of contaminated / non-contaminated populations proposed by Front Studio challenges us to consider the exchange of goods between them. The system must enable the quarantine of people, as well as goods – inevitably establishing an economy of quarantine.

Read More

I’ve joined the masses on twitter. If that’s the kind of thing that you’re into, I’m @eatingbark. Feel free to help me pressure Stephen into doing the same.

The Dirt has a lengthy interview conducted by Pierre Belanger with Joe Brown, chief executive of planning, design, and development at AECOM, the architecture and engineering firm that swallowed EDAW (formerly the world’s largest firm primarily focused on landscape architecture, if I recall correctly). The interview covers a wide range of issues, from the “need to [develop] metrics for… performance-driven, technology-driven planning and design… at the middle scales”, to the potential role of public entities, universities, and private companies in dealing with mass migration and infrastructural reconfiguration driven by climate change, to the emergence of landscape architects as the coordinators of “systems of integration… where site systems interface with spatial experiences and connect with ecological processes”. Some of it — judging by the comments collected so far — may be controversial, particularly digs at New Urbanism (“helpful” but “superficial”) and small firms (“partitioning and fractioning… goes ‘against the grain of [interdisciplinary] cooperation'”), but Brown offers a tantalizing glimpse of a totalized and highly rational approach to the design of infrastructure and the planning of cities, as well as an entirely different role for landscape architects. It’s impossible to know at this point whether the AECOM experiment will be successful or not, but it’ll be worth following, if only for its massive ambition.

[For extra entertainment, contrast the approach to infrastructral intervention described by Brown with that summarized by faslanyc in his post “Tactics vs. Strategy”, and then cross-reference with Varnelis on Banham in Los Angeles, infrastructural decay produced by the severe extension of “neoliberal individual rights”, and “complexity [as] the failure point for post-Fordism” — the last of which is directly challenged by Brown’s vision of totalizing and rationalized infrastructural urbanism; also, I hope I don’t need to bother outlining the images of corporate dystopia prompted by the implication that urban planning ought to be the exclusive domain of a handful of very large design and engineering firms, but they’re there.]

An article from Sunday’s Washington Post discusses the development of “climate defense systems”, resulting from an increasing interest in not just climate change prevention, but also climate change adaptation. The article is particularly focused on the Netherlands, where “the Dutch are spending billions of euros on ‘floating communities’ that can rise with surging flood waters, on cavernous garages that double as urban floodplains and on re-engineering parts of [the] coastline”, as well as “engaging in “selective relocation” of farmers from flood-prone areas and expanding rivers and canals to contain anticipated swells”.

Via @bldgblog‘s link to this great post on the Mexican city of Guanajuato (which I first became fascinated with when the friend who introduced Stephen and I spent part of a summer there with an architecture studio), I see that Brett Milligan, whose project “Inundating the Border” mammoth briefly touched on in an earlier post on Texas hydrology, is writing an excellent blog entitled Free Association Design.

It looks like posting has been fairly infrequent until recently, but the topics are fantastic. Besides the post on Guanajuato, which, as BLDGBLOG says, covers “nonorthogonal grids, partially underground infrastructure, off-kilter houses, and more”, recent posts include a follow-up on the intricate lace of hand-dug mining tunnels which honeycomb the hills outside Guanajuato, a brief review of the Landscape Infrastructures DVD (which neither Stephen or I have finished yet), and global maps of anthropogenic biomes.

Stephen and I were (of course) delighted to have the opportunity to join BLDGBLOG and Edible Geography (as well as many others) over the weekend for the concluding presentation from the Landscapes of Quarantine studio they’ve been conducting this fall. The work that’s being produced (for a forthcoming book and exhibition at the Storefront for Art and Architecture) is every bit as diverse and omnivorous as one would expect.

If you’d like an overview of the work, BLDGBLOG and Edible Geography have written posts on the topic; I’d like to talk about Daniel Perlin‘s project. Perlin, a New York-based DJ and sound artist, derived the inspiration for his project from a recent visit to China, where he saw systems set up (if I recall correctly, in a hotel lobby) that use infrared technology to screen for humans with abnormally high body temperatures (i.e. the sick). The system is composed of a camera, an automated interpretative computer system, a screen on which the computer displays a live feed from the camera overlaid with data points tagging people in view with temperature readings, an attendant, and an alarm (heard by the attendant through an ear piece), all of which appears senseable at first pass, as it seems reasonable that one could use an infrared camera to measure body temperatures and thereby locate (and quarantine) those running fevers. But Perlin noted a variety of ways in which the system can and does malfunction, from operator error (Perlin noted that the attendant was not, in fact, wearing the warning ear bud and so would have missed any warning tones the system generated) to mis-measurement. This sets the system up for two kinds of failure: the inappropriate extension of quarantine (the system mistakenly identifies healthy people as sick and so actually participates in spreading disease, which Perlin, with good cause, described as the most horrific consequence of quarantine he could imagine) and a failure to protect the population (the system fails to identify and quarantine the sick).

Though Perlin’s project explores the former possibility, the latter fascinates me, as it reminds me of the concept of “security theater”, coined by Bruce Schneier to describe the ways in which the public apparatus of security (at airports, government buildings, schools, transit stations, etc.) exists primarily not to provide security, as those measures are demonstrably ineffective, but to provide a fearful public with the illusion of security.

Is there, then, a subset of quarantine practices that ought to be termed “quarantine theater”? Practices which exist not to protect the public from contagion, but to illegitimately pacify the public? As Schneier notes in a recent post on security theater, this has both sinister implications (the practices of quarantine theater might divert important resources away from effective quarantine practices, or produce a false sense of security leading the public to ignore simple but vital practices) and more benign implications (providing a sense of security is not necessarily a bad thing, even if it illusory, if it permits normal life to continue in the face of potential threat).

Of course, this raises the nasty possibility that some of the other participants’ projects or project topics (Front Studio‘s fascinating quarantined city-within-a-city, for instance, or, more extremely, deep geological waste repositories such as Onkalo in Finland, which Smudge Studio’s project explores) are themselves instances of quarantine theater, perhaps necessarily subject to the same sorts of systemic breakdowns. I’d love to see a project which explores what would happen if, for instance, one combined Front Studio‘s key insight (that quarantine could be a distributed condition interspersed within the city) with Perlin’s key insight (that quarantine might be inherently failure-prone), and sought to design a quarantine that is both distributed and redundant.

[You’ll find lots more on security theater in James Fallows’s archives at the Atlantic, though you’ll have to dig around within the “terrorism/security” tag]

[Amos Coal Power Plant, from Mitch Epstein’s fantastic series American Power]

Adrian Lahoud has a lengthy post on infrastructure and urbanism at Post-Traumatic Urbanism; the post is well worth reading. A handful of somewhat scattered comments on it follow.

I strongly agree with the emphasis on “complex urban interdependencies”, in addition to “physical artefacts” of infrastructure. I think Lahoud’s making roughly the same point (that infrastructures cannot be considered as purely physical objects, but must be understood within their social, political, and economic contexts, as well as that those contexts are growing increasingly complex and difficult to process) that Varnelis (along with the other authors) does in The Infrastructural City, which is also well worth reading.

I also appreciate the effort made to link infrastructure and politics:

“If politics means making decisions that divide, then nothing divides quite like the kilometres of concrete and steel that make up a freeway or rail line. By understanding infrastructure as the ‘structuring of access’ we foreground the way it unevenly redistributes opportunity (and cost) in accordance with power. As such it forms a crucible for political activity.”

“This raises the question as to what isn’t infrastructure. The answer to this would be to say that the property of something being infrastructural or not, does not properly belong to the object itself, it emerges through the relation said object has with other objects. If this relationship is a dependent one, in which one object relies on the other for its functioning, then we might say that the second object plays the role of infrastructure. However if the relation between the objects is characterised by autonomy – that is to say independence – then we could not say that the object operates infrastructurally.”

My general thinking is that it’s not particularly helpful to redefine words in a way that makes the conversation inaccessible to someone who isn’t aware of your redefinitions — which is why I’d shy away from using infrastructure to generally mean something other than the common understanding (physical artifacts) — but I’m largely on-board with the notion that, particularly for design purposes, the most interesting and important properties of infrastructures are relational, derived from the active properties of the infrastructures, and therefore best described by the adjective and adverb (infrastructural, infrastructurally), not the noun (infrastructure). Funnily enough, I made this same distinct (between infrastructure and infrastructural) in my thesis.

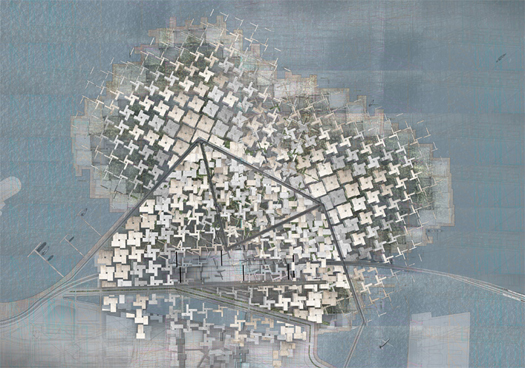

[‘The Diversity Machine and Resilient Network’2, from Lahoud’s studio]

However, I’m not sure that I find the student projects fully convincing instantiations of Lahoud’s rhetoric. They still seem to be “big plans”, which, even on a generous day, I’m ambivalent about the value of. I’d like to think that learning to work infrastructurally (to use Lahoud’s language1) means working more flexibly (despite rhetoric which differs sharply from modernist rhetoric, the two designs presented appear to be close kin of modernist residential housing collectives and contemporary superblocks, as both take a large piece of land and develop urban fabric wholesale upon it), less directly (designing the infrastructure upon which the city grows, with an awareness of how the shaping of the infrastructure will affect the growth of the city, but not presuming to design the city itself) and accepting a degree of loss of control over the aesthetics of the resulting city fabric (which presents a host of drawing problems — how do you draw something which you are not presuming to design and still manage to communicate the importance of the work you’ve done in designing the scaffolding? — but still seems to me to be a humility worth developing).

Having expressed that reservation, I do greatly appreciate the thrust of one of those student projects, ‘The Diversity Machine and Resilient Network’2, which argues that, though Beirut’s “urban fabric… lacks consolidation… optimization or efficiency”, this is not a weakness, but a strength: “it is precisely the ‘redundancy’ of the distributed social infrastructure and relative autonomy of the neighbourhoods that lends the city its resilience.” Though made more specifically in reference to urban form and less in reference to infrastructure, this point reminds me of two things.

[PXP Lease on Jefferson, from CLUI’s slideshow “Urban Crude”, at Places]

First, as faslanyc noted in the comments on a previous post, the impact of an infrastructure on the territory in which it resides should be evaluated not just by its scale, but also for its degree of distribution and connectivity. I don’t think there’s a simple distinction to be drawn between good (distributed) and bad (single entity, to use faslanyc‘s term), but Lahoud and his students do bring up one of the major advantages (resilience) that a distributed infrastructure has over a monolithic infrastructure. A second major advantage motivates Uchitelle (insofar as he is motivated by something more than infrastructural nostalgia) in the “Superproject Void” article I noted previously: distributed infrastructures connect diverse territories and, in doing so, produce economic benefits which cannot be replicated by monolithic and singular infrastructures, no matter how large.

Second, and directly related to that first advantage, I’m also reminded of the article Fracture Critical, which ran recently in Places and draws an interesting parallel between two ways of designing specific infrastructures, fracture-critical and fracture-resistant, and ways of designing larger systems. According to the article, fracture-critical infrastructures and systems (the term orginates within engineering) are defined by four primary characteristics: “lack of redundancy, which makes a structure susceptible to collapse should any individual component fail”, “interconnectedness”, “efficiency”, and “sensitivity to stress”. Though I’ve said that redundancy is one of the key characteristics of a distributed infrastructure, this definition of fracture-critical suggests that there may be an inherent tension between “redundancy” and “interconnectedness”. Given that the consequences of a networked super-project being fractured would be enormous, I suspect that there’s a place for being cautious about the design of such projects, even while recognizing their value.

A few blogs, mostly relatively recently added to the reading list:

Millenium People, which is on an Arctic hiatus, but should return after Christmas; a recommended starting point: the data city + jules verne // Serial Consign, Greg Smith (of Vague Terrain) on “digital culture and information design” // Quiet Babylon; as it says, “cyborgs, architects, and our wierd broken future”; recommended for fans of Bruce Sterling // Urban Tick, a research blog coinciding with studies on cycles, rhythms, space, time and technology within the city at CASA // faslanyc, critical commentary on both landscape architecture practice and other commentary on the same (a representative post: Tactics vs. Strategy: What would Juvenille Do?) // dpr-barcelona, mostly pretty pictures, but with enough context to make them informative (for instance: Nicholas Szczepaniak’s gorgeous Blackwater Estuary warning towers) // Inventing Green, Alexis Madrigal on the history of ‘green’ technology (for instance: The Solar Space Race That Never Was) // and, as a brief but entertaining diversion, looks like dune, a tumblr of images which, in aggregate, will remind one of Frank Herbert’s Dune.

Magnus Larsson, of BLDGBLOG fame, talking about the same project at TED.

[Aerial image of the Hoover Dam Bypass under construction; I’d love to give credit for the image to the photographer, but it came to me through a long email chain, lacking any attribution, and I haven’t been able to locate the source]

Economics journalist Louis Uchitelle complains about a “superproject void” in the Times; Infrastructurist responds, arguing that California’s high speed rail, the nation-wide revival of streetcar networks, and the “smart grid” could all be considered “superprojects”. As commentators point out, he’s also ignoring relatively traditional but underground projects such as Chicago’s Deep Tunnel, the ARC Tunnel, and the third New York water tunnel, and important new-but-distributed infrastructures (the “smart grid”, the replacement of radar by GPS-based flight control). And Infrastructurist is also right to make the Varnelis-esque point that “we’re a heavily populated wealthy democracy with a dysfunctional political culture that favors paralysis over action,” though it’s a point that runs counter (as Infrastructurist states) to the overall theme of the post.

That said, Infrastructurist doesn’t really respond to Uchitelle’s points about the relationship between scale and economic effect, as Uchitelle is arguing not just that that contemporary infrastructure projects are smaller, but that there’s something fundamentally different about the economic effect of a very large project, like the ARC Tunnel, which, while physically impressive, operates in a relatively small geographic territory, and a superproject, which connects formerly disconnected territories (as the interstate highway system did), aggregating markets. The obvious contemporary corollary to the interstate is high speed rail, but Uchitelle also rightly notes that the Obama administration project which is closest to a superproject, defined not just by impressive physical impact, but also by economic effect and ability to facilitate new connections, is the proposed integrated health care computer network.

There’s nothing particularly original about the observation that the Dutch have a peculiar national relationship to their landscape (and, in particular, its hydrology), but that peculiarity produces endlessly fascinating oddities and, apparently, endless mammoth posts on Dutch hydrology. As lewism noted on one such post, Bulwarks and Flux:

…the whole of Dutch landscape and history can be seen as a kind of resistance to and acknowledgment of the sea. The polder system, which is on the surface just a land reclaimation sytem, is for a Dutchman something more… a political sytem, an ownership structure, a landscape…

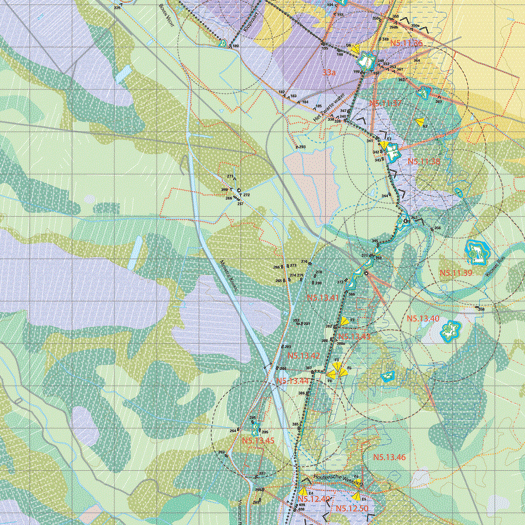

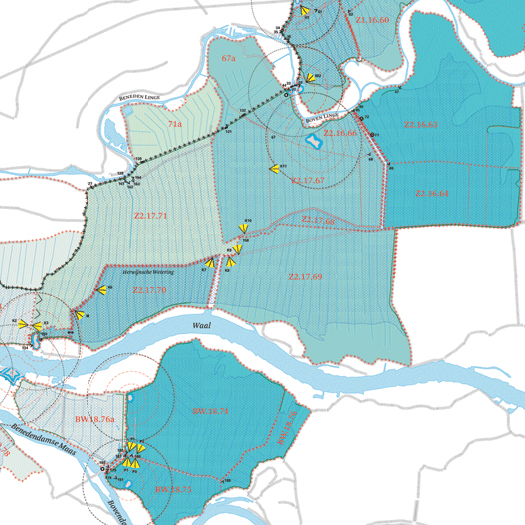

One of those oddities, the Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie (alternately known in English translation as the New Dutch Water Defense Line and the New Dutch Inundation Line), is the subject of this post.

The original Dutch Water Line (whose function and mechanism can be easily dervied from the variables in the English translation, “inundation line” and “water defense line”) dates to 1629, when Prince Frederick Henry, inspired by the successful use of flooding as a defense mechanism during the Dutch War of Independence, began to execute a plan to construct a “line of flooded land protected by fortresses”:

Sluices were constructed in dikes and forts and fortified towns were created at strategic points along the line with guns covering especially the dikes that traversed the water line. The water level in the flooded areas was carefully maintained to a level deep enough to make an advance on foot precarious and shallow enough to rule out effective use of boats (other than the flat bottomed gun barges used by the Dutch defenders). Under the water level additional obstacles like ditches, trous de loup and later barbed wire and mines were hidden. The trees lining the dikes that formed the only roads through the line, could be turned into abatis in time of war. In wintertime the water level could be manipulated to weaken ice covering, while the ice itself could be used when broken up, to form further obstacles that would expose advancing troops longer to fire from the defenders.

This national defense system of weaponized artificial hydrology proved remarkably successful during the 17th century, halting Louis XIV’s invasion of the Netherlands, but less so in the 18th, when the French took advantage of winter ice to bypass the Water Line.

The idea of weaponized hydrology was firmly ensconced in the national consciousness, though, and, after the formation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in the early 19th century solidified national borders, the Nieuwe Hollandsche Waterlinie was constructed to the east of the original Waterlinie. Between three and five kilometers wide, the zone of potential inundation stretched “approximately 70 kilometres from Muiden (situated on the Zuiderzee, currently Ysselmeer), past the city of Utrecht towards the east, down to the large river district (the Nieuwe Merwede) and the Biesbosch,” at a depth of 35 to 50 centimeters (just deep enough to prevent crossing with artillery, but not deep enough for boats) — approximately one hundred and seventeen thousand cubic meters of ominously empty space, imbued with military potential:

The system consisted of 6 what is termed inundation basins, which could be regulated by dikes, culverts, canals, fan locks, dams and sluices. A system of defences, such as forts (covering 2 hectares to 32 hectares) was located at the accesses to the inundations, e.g. near higher roads, or where the inundations could be traversed via existing dikes, lakes or rivers and wherever it was necessary to protect the inundation facilities. There were more than 60 defences of varying types in this Inundation Line. Civil and military roads (available for civil use during peacetime) were also a part of the Inundation line. Planting of the defences was strictly regulated. The permanent defences varied from simple earthworks without permanent buildings to earth defences with brick turrets, ‘turret forts’, bomb-proof barracks, guardhouses, casemates and bomb-proof shelters for artillery…

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the fortifications that sat along the Waterlinie gradually grew in thickness and armament, mirroring increases in the potency of field gun and artillery technology. Care was taken to blend these fortifications into the landscape, in what might described as a landscape architecture of military concealment:

This [concealment was accomplished] by presenting low and vague contours for the defense works when looking from east and south directions. They used ground covering and also bushes and trees of the same kind as in the surrounding landscape. Existing tree lines were extended to cover fortresses.

In World War II, though, the Waterlinie proved unfortunately obsolete, as German forces parachuted behind the Waterlinie to seize key objectives, including bridges into the heart of the Netherlands, and forced Dutch surrender through the devastating aerial bombardment of Rotterdam, in both cases bypassing the Waterlinie. Though there was some attempt at reconstituting the Waterlinie during the fifties as a barrier to Soviet invasion (enhanced by the deployment of anti-aircraft weaponry), the Waterlinie have now all passed in obsolesence.

For the most part, their contemporary fate is that typical of most obsolete fortifications, serving as interesting but relatively obscure tourist attractions. More recently, land artist Agnes Denes was apparently engaged to develop a master plan for the Waterlinie “incorporating water and flood management, urban planning, historical preservation, landscaping, and tourism,” the specific contents of which are listed as an “Inundation Map; Proposed Forestations; Proposed Windmill Locations; Present/Proposed Wildlife Preserves, Wildflower Meadows and Gardens; and Proposed Crystal/Glass Fort” (the last of these is rather unfortunate and can be seen here). While I haven’t found any detailed information on Agnes’s proposal, I’d like to think that a more interesting and significant future (than as permanent tourist attractions) is possible, emphasizing the uniqueness of a corridor in which the Dutch inverted their traditional relationship with the sea, building canals and sluices not keep the water out, but to let the sea in.

[awareness of the existence of the New Dutch Water Defense Line via Kosmograd’s recent post highlighting the gorgeous atlases produced by Dutch (graphic) designer Joost Grootens, whose subject matter include the New Dutch Water Defense Line, the relationship between the northern limits of Roman control in the first couple centuries A.D. and contemporary Dutch urbanism, and a comparative look at 101 of the world’s largest cities; CLUI apparently did some research (file is a pdf, but lacks the extension; you’ll have to save the file and rename it .pdf in order to read it) in 2001 on the Waterlinie, but I haven’t found many details]

Strangely affecting photographs of Ordos under construction, via delicious/sevensixfive; my previous thoughts on Ordos here.

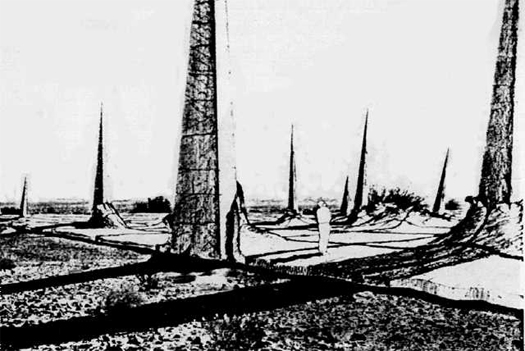

[“Landscape of Thorns”, concept by Michael Brill and drawing by Safdar Abidi, from Marking the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant for 10,000 Years]

Triggered by the recent revelation that tests at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory reveal that a seemingly innocuous white substance filling a glass bottle dug up in 2004 is actually “the oldest existing sample of bomb-grade plutonium from a nuclear reactor, with a half-life of 24,110 years,” Juliet Lapidos reviews the Department of Energy’s 1993 recommendations for the construction of a massive nuclear-waste disposal warning landscape. The trouble, of course, is that anything one does to communicate danger is likely to also communicate mystery and excitement to future treasure-hunters or archaeologists:

The report’s proposed solution is a layered message—one that conveys not only that the site is dangerous but that there’s a legitimate (nonsuperstitious) reason to think so. It should also emphasize that there’s no buried treasure, just toxic trash. Here’s how the authors phrase the essential talking points: “[T]his place is not a place of honor … no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here.” Finally, the marker system should communicate that the danger—an emanation of energy—is unleashed only if you disturb the place physically, so it’s best left uninhabited.

As for the problem of actually getting these essentials across, the report proposes a system of redundancy—a fancy way of saying throw everything at the wall and hope that something sticks. Giant, jagged earthwork berms should surround the area. Dozens of granite message walls or kiosks, each 25 feet high, might present graphic images of human faces contorted with horror, terror, or pain (the inspiration here is Edvard Munch’s Scream) as well as text in English, Spanish, Russian, French, Chinese, Arabic, and Navajo explaining what’s buried. This variety of languages, as Charles Piller remarked in a 2006 Los Angeles Times story, turns the monoliths into quasi-Rosetta stones. Three rooms—one off-site but nearby, one centrally located, and one underground—would serve as information centers with more detailed explanations of nuclear waste and its hazards, maps showing the location of similar sites around the world, and star charts to help intruders calculate the year the site was sealed…

Proposals for the “earthworks” component demonstrate that the whole project of communicating with the future is really a creative assignment, more dependent on the imagination than on expertise… The report proposes a “Landscape of Thorns” with giant obelisklike stones sticking out of the earth at odd angles. “Menacing Earthworks” has lightning-shaped mounds radiating out of a square. In “Forbidding Blocks,” a Lego city gone terribly wrong, black, irregular stones “are set in a grid, defining a square, with 5-foot wide ‘streets’ running both ways. You can even get ‘in’ it, but the streets lead nowhere, and they are too narrow to live in, farm in, or even meet in.”

The full report, Expert Judgment on Markers To Deter Inadvertent Human Intrusion Into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, is, as Lapidos notes, a “bizarrely fascinating read”, with the last two appendices, in particular, reading like summary notes from some intensely strange landscape architecture studio, filled with durability comparisons between concrete monoliths and Egyptian pyramids, poetic denunciations of the buried wastes (“What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us…”), suggestions that the waste site be constructed in the form of a massive global map of similar nuclear waste repositories, geologic cross-sections of the repository, fictionalized accounts of the arrival of explorers on the site in some distant future, and even the suggestion that the site be carved into massive “Aeolian structures”, noting that “sounds that can readily be generated by long-lasting aeolian structures turn out often to be dissonant and mournful”, neatly lining up with the general atmosphere of “great foreboding” to be produced. The description of the proposed “Black Hole” is typical:

A masonry slab, either of black Basalt rock, or black-dyed concrete, is an image of an enormous black hole; an immense nothing; a void; land removed from use with nothing left behind; a useless place. It both looks uninhabitable and unfarmable, and it is, for it is exceedingly hot part of the year. Its blackness absorbs the desert’s high sun-heat load and radiates it back. It is a massive effort to make a place that is fearful, ugly, and uncomfortable. The heat of this black slab will generate substantial thermal movement. It should have thick expansion joints in a pattern that is irregular, like a crazy-quilt, like the cracks in parched land. And the surface of the slab should undulate, so as to shed sand in patterns in the direction of the wind.

One could easily imagine some future Severian, wandering his future Urth, encountering these constructed waste-fields but as blissfully unaware of their intended warnings as he is that the dungeon-like tower he was raised in was once the launch complex of a vast spaceport. But even if you could design a landscape so obviously “fearful, ugly, and uncomfortable” as to disquiet this imaginary Severian, you still encounter the crux of the problem: how do you design a landscape which is universally repulsive, without attracting those who are fascinated by repulsive landscapes?

[Edible Geography and BLDGBLOG’s recent interview with Department of Energy scientist Abraham Van Luik briefly touches on the WIPP, and should be of interest if you’ve read to the end of this post]

A couple months ago, The Dirt highlighted an article from the Times about Alabama’s “War on Cogongrass”, in which Alabama’s forestry commission and a hired company of landscape managers, Mobile’s Larson & McGowin, deploy a series of escalating military metaphors (“killer”, “the Perfect Weed”, “war project”, “parallel attacks”, “eradicate”) against that rather aggressive species.

Alabama’s approach is perhaps a bit extreme in metaphor, but it is representative of the typical way in which invasive species are approached: as unwelcome interlopers disturbing peaceful ecosystems, evidence of the folly of simplistic and domineering early twentieth-century attitudes towards the human re-deployment of flora. But that attitude, too, may itself be simplistic. A recent article at Slate, Are invasive species really that bad for the environment?, summarizes scientific push-back against the making of binary distinctions between ‘native’ and ‘invasive’ plants:

…A growing contingent of scientists is advocating a more neutral attitude. Certainly, they say, non-native plants and critters can be terribly destructive—the tree-killing gypsy moth comes to mind. Yet natives such as the Southern Pine Beetle can cause similar harm. The effects of exotics on biodiversity are mixed. Their entry into a region may reduce indigenous populations, but they’re not likely to cause any extinctions (at least on continents and in oceans—lakes and islands are more vulnerable). Since the arrival of Europeans in the New World, hundreds of imports have flourished in their new environments. Common wildflowers such as Queen Anne’s lace and certain kinds of daisies are “naturalized” aliens. The storied apple tree originally hailed from Asia…

There’s an argument that even the dichotomy between “native” and “non-native” is ultimately meaningless. Species have always migrated; to identify one as native is to draw an arbitrary line in time. Davis favors a continuum, using labels such as “long-term resident” and “recently arrived”—the idea being that these terms are both more accurate and less loaded.

The debate is ultimately rooted in deeper and more fundamental arguments about the relationship between human culture, natural culture, and wilderness. As the idea of “nature” as something distinct from ourselves is in and of itself necessarily a social construct (there can be no idea of nature without a society to formulate it), so too the notions of the native plant (good) and the invasive plant (bad) are social constructs, though saying that something is a social construct is often misunderstood as an attack on the independent existence of the thing-in-itself, when it is more properly a way of re-examining our (human) relationship to a thing we misunderstand as existing wholly independently of ourselves.

One obvious implication of a more nuanced understanding of our relationship to nativeness and invasiveness is that, as Edible Geography notes, we can begin to think of species range and distribution as things to be cultivated:

It’s a radical idea: the scientists at Chicago Botanical Garden have determined that preserving the prairie ecology includes working out how to relocate it somewhere else altogether. Pati Vitt, a Conservation Scientist at the garden and one of the paper’s co-authers, told the Times reporter that, “I won’t be around in 100 years, but if the research isn’t there, we won’t know how to do it on that scale. That’s why the seed bank is so important.”

As Nijhuis points out, the implications of assisted migration directly contravene “the traditional conservation notion – call it an illusion, if you like – of a place to get back to.”… Their co-authored paper, “Assisted migration of plants: Changes in latitudes, changes in attitudes,” calls for globally agreed seed-banking and future-habitat-matching protocols. With a vision that rivals the space mirrors and artificial clouds of geo-engineering for sheer speculative wonder, Dr. Havens, Dr. Vitt, and their colleagues propose that plant conservationists around the world should be working as all-inclusive real estate agents, hunting down the next home for their clients before helping them pack up and move in.

I’m reminded of a studio project I once did (the particulars of which are not really worth sharing), in which one of the tangential approaches I developed involved using the Forest Service’s fantastic (in content, though not presentation) Climate Change Tree Atlas — it’s a literal atlas of the future (see, for instance, Kentucky Coffeetree evacuate Kentucy in favor of upstate New York and Minnesota, or Longleaf Pine slipping into the forests of Tennessee and New Jersey) — to anticipate what tree species might want to march through Virginia’s Prince William Forest Park in the coming century, and then proposed seeding those species along existing lines of disturbance (transmission lines, etc.) in the park. Which is not nearly so grand as Havens and Vitt’s call for a worldwide redistribution of species, but it does suggest that thinking of species range as something to cultivate (or hack!) opens up a fascinating territory for the landscape architect.