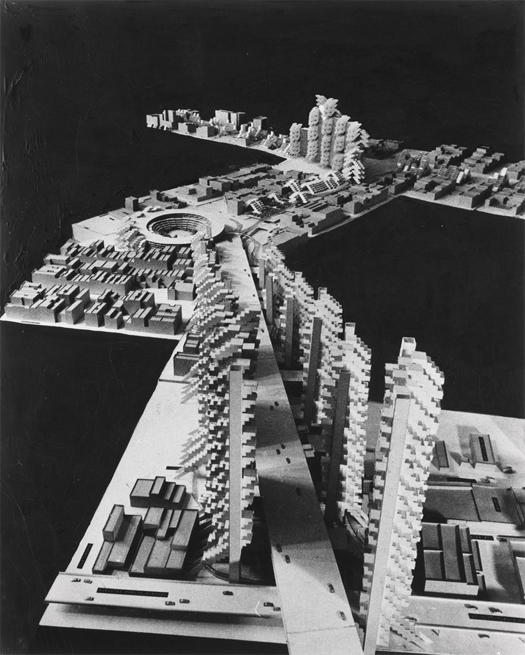

[Photo of Global III, by Alan Berger via NAi Publishers]

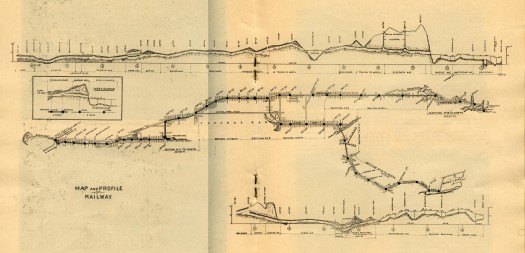

Approximately seventy-five miles due west of the gleaming towers of Chicago’s Loop, Union Pacific Railroad, the United States’ largest railroad company, operates the Rochelle Global III Intermodal Facility, twelve-hundred acres of switching yards, train tracks, loading facilities, and container-sized parking spaces. Rochelle, a small Midwestern town with just under ten thousand inhabitants, has long been a significant crossroads for trans-continental infrastructures. In 1854, the Air Line Railroad ran the first tracks through the town, tracks which are now owned by Union Pacific. In the early 20th century, east and west bound automobiles passed through Rochelle, as the town lies on the route of the Lincoln Highway, the first coast-to-coast highway dedicated in the United States. The town recently commemorated this history with the incorporation of Railroad Park, which it claims is the nation’s first park dedicated primarily to watching trains operate2. Whatever the veracity of that claim, there is no doubt that there are many trains to watch in Rochelle, as every day over three thousand containers pass through the flat and linear landscape of Global III on an average of twenty-five trains. Yet as impressive as the Global III’s scale and swiftness of operation is, it is only one of five Intermodal Facilities operated by Union Pacific in the Chicago area, and the Chicago area facilities are situated within Union Pacific’s much larger network of tracks, rail and hump yards, depots, terminals, and facilities which sprawls across mountains, deserts, plains, forests and coasts from New Orleans to Seattle to Los Angeles and back to Chicago.

Given the potent role logistical networks such as the one that Global III is a single node in play in shaping the form of cities, it is not surprising that contemporary architects, landscape architects, and urbanists of other varying stripes have developed a strong interest in the aesthetics and function of infrastructural landscapes like Global III.

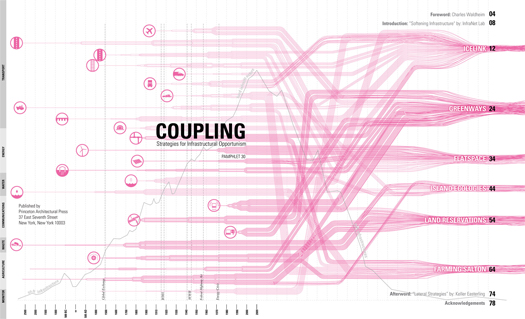

It is also not surprising that the cover of a publication which aims to capitalize on and catalog architectural projects resulting from that interest, as Kelly Shannon and Marcel Smet’s The Landscape of Contemporary Infrastructure — the publication where I first encountered Global III — does, is adorned with the photograph of Global III from the top of this post, neatly rowed trains and splayed geometric parking spaces in the foreground, the facility’s stormwater detention ponds triangular in the background. What is perhaps somewhat surprising, though, is that such a book features on the cover one of the few projects within its pages for which neither architect nor landscape architect is credited. The authors have a rather full palette of projects to select from, including seventy-two “majors” – projects which receive detailed two-page spreads – and numerous “minors”. Of the “majors”, only two – the Hangzhou Bay Bridge and the Qinghai-Tibet Railroad – lack a recognized architect or designer. Global III is only mentioned briefly in the text, as a “minor”, included to serve, along with the Qinghai-Tibet Railroad, as an example of what the authors describe as infrastructures whose “mark of technological ability resides not so much in their expression of sophistication and stylishness, but in the raw force of technological advancement required to master the demanding objectives they were set to resolve”. As the architectural professions are built upon the mastery of “sophistication”, “stylishness”, and “expression”, but not upon the ability to drive technological innovation, the selection of this rather unrepresentative infrastructure for this book’s cover perhaps unintentionally precisely locates one of the core dilemmas produced by the infrastructural turn in the architectural professions: while it is easy to understand why architects want to design infrastructures – as infrastructures are the bone and sinew of modern cities, those who design infrastructures design cities – it is much more difficult to explain why cities should want infrastructures designed by architects.

The reason this question is so difficult to answer is that the very form of these structures — the engineered purity that makes them so compelling aesthetically — arises directly from the spatial ramifications of raw numbers and patterns of logistics. This is a particularly chilling point for architects interested in infrastructure, because, if form-giving is not to be our gift to infrastructure, what will? The obvious response (which mammoth and others have discussed elsewhere) is that if architects want to be more than infrastructural decorators, we’ll need to learn to manipulate the performance-derived source-code that controls the spatial expression of infrastructures. But that is much easier said than done.

So that wrapped up pretty neatly, and consequently I’m not sure how to fit this thought in, but I also suspect that the answer to this question — and other questions related to the involvement of the architectural professions in the future of cities — has a lot to do with the application of “spatial intelligence”, the strategic re-positioning of architecture as a discipline, and, perhaps a little bit less directly, our professions’ facility with what Bryan Boyer brilliantly calls “matter battles”. (Boyer positions the matter battle roughly in opposition to the fluidity of digital design, but I think it could pretty easily be understood as a weakness in purely economic and political models of the city, as well.)

The middle link there, by the way, is to Rory Hyde’s piece from the end of last December on “Potential Futures for Design Practice”, which was not only a superb summary of some of those futures, but also sparked a discussion in its comments section which is not to be missed. That discussion is really worth reading in its entirety, but if you’re looking for a one-sided (but excellent) set of Cliff Notes, Boyer compiled his contributions to the discussion on his own blog.