At the end of October, Hillary Brown — founding principal of New Civic Works, a consulting firm which “promotes the adoption of sustainable design principles for buildings and infrastructure”, as well as a professor of architecture at the City College of New York — published an article on Places entitled “Infrastructural Ecologies: Principles for Post-Industrial Public Works”. As you might expect, that title — infrastructure! ecologies! post-industrial! public works! — drew mammoth‘s immediate attention.

Though the central aim of the article is to provide a set of principles for what Brown describes as “the next generation” of American public infrastructures, the article can really be divided into three parts. First, Brown provides an excellent summary of what might be called the infrastructural public policy problem:

Unfortunately, despite its ambitious label, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act doesn’t even begin to get us to [a] next generation [of infrastructures]. ARRA’s investment in infrastructure — $132 billion out of the total package of $787 billion — is a fraction of current needs, and for the most part it bolsters our dependence on dirty, carbon-intensive construction, underwriting an assortment of backlogged, so-called shovel-ready projects. (As of this writing, there is insufficient detail on the breakdown of the Administration’s proposed $50 billion in additional funding to merit comment.) Twenty percent of ARRA’s infrastructure funding, or $27.5 billion, is dedicated to roads and bridges, which overshadows the $17.7 billion for mass transit and rail systems. [1] $8 billion is targeted for nuclear power plant remediation, but just $2.5 billion for renewable energy networks. The $4.5 billion allocated to basic electrical grid upgrades [2] is a mere tenth of the projected $40 to $50 billion needed. [3]

In prioritizing private over public transportation and short-changing cleaner energy projects, ARRA has undercut the Obama administration’s claim to support a green economy. Still more worrisome, unbalanced investments that favor the old over the new position us unfavorably in comparison to other industrialized nations, which are investing heavily in public transit and renewable energy. [4] Worse yet, they perpetuate America’s disproportionately high per-capita carbon dioxide emissions: approximately 20 metric tons to Europe’s 9 and India’s 1.07. [5] Ultimately, of course, ARRA was more stop-gap compromise than comprehensive vision — and no doubt the hard-fought result of tense partisan politics. Still, ARRA 2009 will be remembered as a tragically missed opportunity at a pivotal moment in national history. And now, it seems, given the tepid response to the latest proposed infusion of funding, complacency may have set in; a public that has misconstrued a short-term stimulus as a long-range solution seems more focused on shrinking government than on endorsing investments in a 21st-century American infrastructure.

Brown is hardly the first to note this, but it is refreshing to see an article that aims at providing design principles for infrastructure begin by acknowledging the depth and scope of the gap between America’s need for new infrastructures and the political will to fund the construction of those infrastructures. (The article perhaps fails to sufficiently emphasize the contribution of NIMBYist forces and dysfunctional political structures to the infrastructural crisis she describes, but it at least hints in those directions. As we’ve discussed those matters elsewhere and, we are sure, will continue to discuss them in the future, we’re following Brown’s lead in this post.)

The third piece of Brown’s article (we’ll get to the second in just a minute) responds to this first challenge, making a proposal for a federal pilot program for infrastructural innovations:

Imagine, for instance, a small federal program aligned with the proposed National Infrastructure Bank, which would be charged with seeding progressive investment agendas and identifying promising infrastructural systems. This new program could privilege projects that were multi-purpose, carbon-efficient and resilient, and based upon well-developed regional transportation or public utility plans. It might recruit domestic or foreign investment, award grants, and provide loans or tax credits. It might award challenge grants, for example, to public/private infrastructural partnerships that integrate land use, housing, transportation, and energy, or that foster co-location and enhance community life. Such an enterprise would be charged with assessing social, economic and environmental returns on investment and ensuring political neutrality, accountability and transparency. Importantly, it would also focus on regulatory coordination and on interagency and cross-sector collaboration, and it would mandate speed, quality and other performance criteria. Lastly, it could promote alternative infrastructural delivery models, with design and construction procurements and contracts that reward innovative, cooperative accomplishments.

This proposal is certainly intriguing, and one which mammoth would like to see fleshed out and discussed further, particularly in a policy context. (We have little doubt that a majority of architects and landscape architects would support a program of experimental infrastructures, but it would need to be shown that the idea makes sense in the ways that Brown describes, not just as an employment program for out-of-work designers. Perhaps Brown has already done this elsewhere? The piece on Places is too short to do it.)

The primary substance of the piece, though, is the second component, which is, as the title of the article promises, a list of design principles. Brown provides four: infrastructures should be “multipurpose, interconnected and synergistic”, “captur[ing] efficiencies by integrating diverse functions”; they should be modeled on and incorporated into natural processes; they should couple (to borrow a term from Lateral Office) their ostensible functions with additional programming which serves the needs of the communities that they are built within; and they should be resilient, particularly in the context of instability produced by climate change.

[1] Though we’ll note that, if there’s anything here that makes us uncomfortable, it’s the third principle, which — particularly in the examples given — feels dangerously close to the suggestion that every infrastructure can be improved by making it also a public space. We don’t doubt that many infrastructures could be improved by coupling them with public spaces, or providing public access to them. But as FASLANYC notes in a comment on Brown’s piece:

“Also, it is striking that whenever landscape architects are involved in making multi-functional infrastructures or whatever, the contribution seems to be “umm… i don’t know… we could make a park… yes, we need a park there by the nuclear cooling towers!” and then renderings are produced with lots of lawn and cyclists. yikes.”

A highway. And a park. A bridge. And a park. A sewer treatment plant. And a park.

Our hesitant reaction is less a function of concern about the appropriateness of layering public space onto infrastructures (often quite appropriate) than it is disappointment that adding public space (why always parks? why not a mall? malls are significant public spaces, though much less romanticized than parks) is assumed to be automatically helpful, which has the detrimental effect of discouraging reflection about whether this hybridization is appropriate in a given case, so that public spaces becomes a default add-on option for new public works, like bad sculptures in front of mediocre condo towers.

While the principles feel to some degree underdeveloped — why, for instance, think about instability only within the context of climate change, when an increasing awareness of the presence of uncertainty in all complex systems is a recurrent theme in both contemporary urban and contemporary architectural thought — this is probably as much a function of brevity as anything else. Each of them feels, at a minimum, potentially useful, and we suspect that a program of infrastructural construction centered around them would be a vast improvement over our current national infrastructure [1].

What seems missing to us, though — and critical to understanding the peculiar value that infrastructures have as objects of design — is a discussion of infrastructure as a point of agency for designers operating in urban systems. How can infrastructure, in other words, be used to organize urban systems?

Here, it’s useful to step away from infrastructure for a minute, and think about the arguments that landscape urbanists — particularly James Corner and Charles Waldheim — made in the seminal text of landscape urbanism, The Landscape Urbanism Reader. There (and elsewhere), Corner and Waldheim describe and define landscape urbanism as a design movement which is specifically constructed in reaction to the failures of traditional modernist planning. Though the various essays in that text name multiple points of failure, notably including a split between art and instrumentality in landscape design practice and the construction of binary oppositions, particularly between culture and nature, the most important of them for our discussion is modernism’s object fixation, which manifests in architectural and planning practices as a tendency to view cities as collections of static objects and to use static tools — ranging from McHargian environmental preservation, to traditional zoning, or even to New Urbanism’s form-based codes — as the primary tools for ordering cities. (Of course, object fixation has persisted in architecture and landscape architecture long past the expiration of modernism as a coherent consensus within design.)

The landscape urbanists argue that these tools are inherently flawed, that methodologies which seek impose control on urban systems are fundamentally ill-suited to operation in the contemporary city. While this point could be overstated — clearly, zoning, for instance, is an effectual tool for ordering cities, though it often produces massive unintended consequences — we agree that more and better tools are needed, particularly those that are effective in indeterminate, fluctuating conditions.

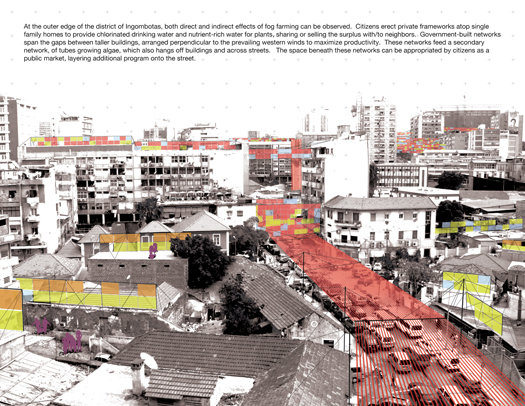

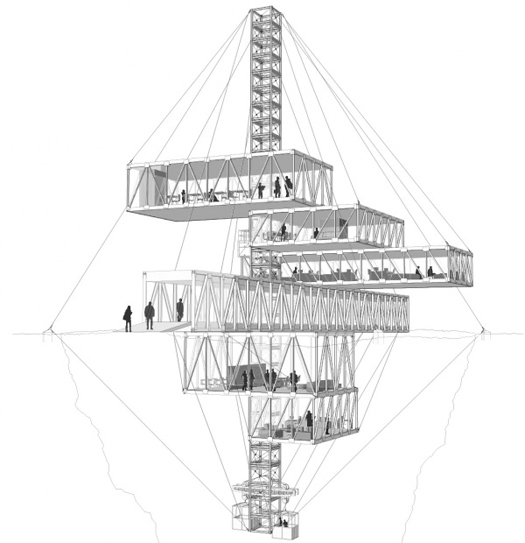

[2] It’s worth noting here that there is obvious overlap between the potential latent in infrastructure which we are describing, and the tussle to describe an appropriate alternative to modernist planning which we have recently discussed. We described this infrastructural potential with a more explicit focus on that overlap in our Bracket 1 essay, Hydrating Luanda:

“We suggest that infrastructure is an appropriate object of design for the urbanist, the architect, and the landscape architect, as infrastructure can be embedded with some characteristics that provide definition (a means for the urbanist to have influence on the direction of change), as well as characteristics that permit appropriation by inhabitants of the urban system. In other words, an infrastructure can withstand appropriation while remaining coherent as an intervention.”

This is where infrastructure seems peculiarly useful to us. In Stan Allen’s monograph/manifesto Points + Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City, Allen describes infrastructures as elements in urban systems which, “although static in and of themselves… organize and manage complex systems of flow, movement, and exchange. Not only do they provide a network of pathways, they also work through systems of locks, gates, and valves — a series of checks that control and regulate flow.” The potential of infrastructure, Allen argues — and we agree — resides in its ability to be at once “precise and indeterminate”, to specify both “what must be fixed and what is subject to change” [2].

In other words, an infrastructure can be a stable element which molds and manipulates the various flowing processes of urbanization which produce cities: economic exchange, human migration, traffic patterns, informational flows, legal conditions, political actions, hydrologies, waste streams, commutes, even wildlife ecologies. Both governments and private developers have historically sought to harness this potential, whether by profiting from the sale of land along new infrastructures or by reinforcing growth and density in a locale by supplementing existing infrastructures.

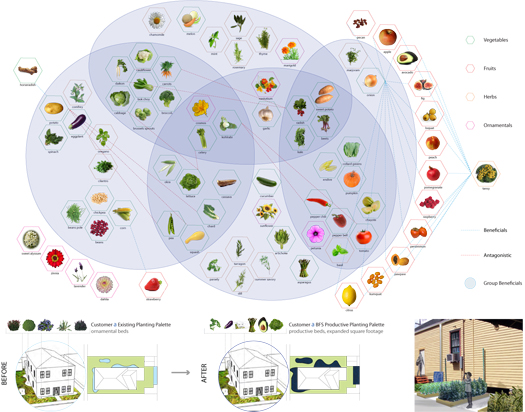

[3] This generative potential, of course, exists to some degree in all built objects, and so it seems appropriate to say that designing in this manner is not just designing infrastructure, but designing infrastructurally. Libraries, parks, plazas, apartment buildings, factories, and all other objects of architectural design can and should — at least at times — be designed infrastructurally. One particularly potent example of this which mammoth has described before is the building program in Medellin, where architectural projects were treated as opportunities to catalyze reactions within the urban system.

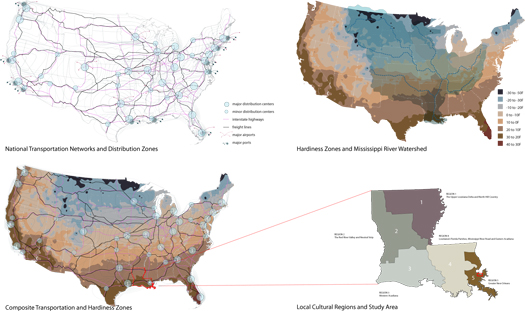

[4] The economic and performative aspects of infrastructure aren’t the only ways in which they generate urbanism; their phenomenal qualities can do so as well — for example, where freeways were run through more densely built environments, they bifurcated and compartmentalized neighborhoods.

This capacity of infrastructure, distinct from its capacity to carry the flows that it is specifically intended for (such as electricity in the case of power lines, or traffic in the case of highways), might be termed generative. Generative capacity, then, is the effect on an infrastructure on the territory in which it resides [3]. The American interstate highway system, for instance, was built because it had the capacity to enable people and goods to move rapidly and with great independence. Beyond that specifically intended effect, though, it also served to produce a novel and ubiquitous form of horizontally-distributed urbanism, as first services stations and stores and later entire towns clustered around on and off-ramps [4]. No one had to plan this new urbanism; it emerged from a confluence of economic and spatial incentives, binding together on an infrastructural framework in built form.

Understanding and appropriately wielding this generative capacity is, we believe, the single most important task for architects and landscape architects to undertake if they want to participate in the design of a new generation of American infrastructures, because it promises an alternative instrument for guiding the growth of cities, one which combines the unified vision of top-down planning with the vibrancy and resilience of emergent growth.